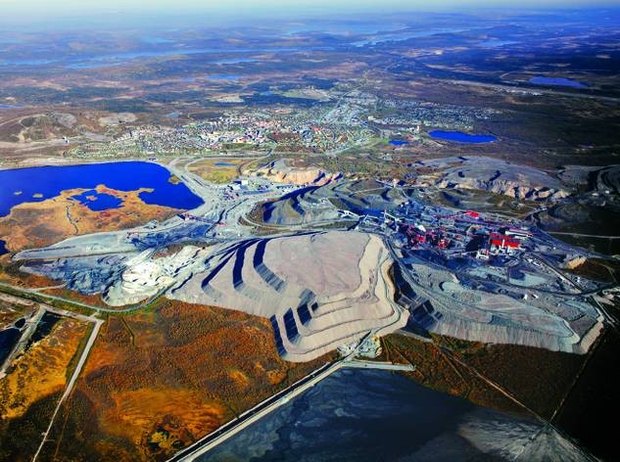

Ariel photograph of Kirua, the largest iron-mine in Europe. By 1990 one billion tons of iron-ore had been produced. Note the heaps of slag. Photo provided by LKAB.

The Mining Inspectorate of Sweden (Bergsstaten) is the official body responsible for issuing prospecting permits, i.e. in relation to the exploration for minerals. It also issues exploitation concessions, i.e. permits to operate mines. Thirdly the Inspectorate carries out inspections and provides information.

The head-office is in Luleå, in northern Sweden and thus is situated close to the large iron and sulphide mines of northern Sweden. A subsidiary office is located in Falun in central Sweden, the other major mining district of the country. Of the possible eighteen new mines some will be in the northern part of the country. The majority will however be located in central Sweden.

- What then is behind this expansion of mining in Sweden?

- One reason for this is that we have seen a significant global increase in the level of demand for minerals and this has been reflected in a relative increase in price levels on the metal-market. Secondly, the liberalisation of prospecting, which Sweden introduced in 1992-93, has also had an impact here.

- A major issue in respect of any debate on mining is the environment?

- We have said that landscape changes will be restricted as far as possible and in addition require that some fifteen years after a mine has closed that woods should be growing over the site once again. Usually however the most challenging issue concerns how to avoid toxic discharges. For example arsenic is one of the most widely used substances in the process of extracting gold or copper and should obviously not end up being discharged into the natural environment.

- Sweden has very strict regulations with regard to the environment. In this context it could be argued – rather than cause environmental damage in desperately poor countries abroad – that we have a moral obligation to extract minerals at home. In fact Europe produces only around four percent of the total world production of metals and minerals while it consumes some 20-25 percent.

- As far as the location of mines is concerned there are a number of important issues relating to transport and the proviso that existing communities should not be disturbed. A third challenge here relates to the question of reindeer-herding. The areas attractive to prospectors looking to open new mines in the northern parts of Norway, Finland and Sweden are generally the same as those used for reindeer grazing.

The Chief Mine Inspector explains that the ownership of land in potential mining-areas is mixed. On average around half of such land is owned by the Swedish state, a quarter by large companies and the final quarter by smaller owners.

The mine-companies generally lease the ground they need and pay 0.15 percent of the annual gross income. In other words the rent varies with prices on the mineral market. A few examples also exist of mining-companies actually buying land for exploitation. In cases like this the price is usually the value of any woods on the site plus 0.15 percent of the expected profits.

- Usually no major discussion takes place over what should be paid for access to the land and the ore deposits it contains, particularly as such costs are small compared to what must be invested in machinery and transport, explains Jan-Olof Hedström.

Together with Sweden, Poland, Spain and Russia are the largest mining-countries in Europe. Sweden is without doubt the largest in the iron field and number two or three as regards lead, copper, silver, gold and zinc.

- The Second World War demonstrated the strategic importance of metals such as iron ore as exemplified by the mines of Kiruna. Germany was very eager to secure for herself these mineral resources?

- True and Sweden had to play a difficult hand in order to stay out of the war. Today, however I think the challenges are rather more that the major so-called third world mineral producers will likely reduce their exports to the rich countries in future. They will increasingly want to keep more of these resources for their own development.

- In terms of oil and gas much is often made of the amount remaining to be discovered. Many argue that as much as a quarter of these resources are to be found in the Arctic. Can such an argument be applied to minerals?

- I guess that I am too serious to adhere to such speculation. However, let me say that the kind of rock formations we have here in the northern Baltic-Scandinavian area can also be found in parts of Northern and Southern America as well as in Australia. This means that all these areas show a major potential for future mineral extraction.

Hedström underlines that, for Sweden, mining has also given them the possibility to develop industrial concerns relating to explosives, equipment, transport etc., like Nobel, Atlas Copco, Sandviken and others. - The fact that these companies have had the ability to test their products on nearby sites has been of the utmost importance, he adds.

Jan-Olof Hedström, the Swedish Bergmästre outside his head-quarters in Luleå.

Photo: Odd Iglebaek

The birth of a new iron-mine, here we see the test-tunnel at Stora Sahavaara near Pajala.

Photo: Odd Iglebaek

By Odd Iglebaek