Ageing of the population is not unique to the Nordic countries, as it is a clear trend in most European countries. The 2012 report Global Population Ageing: Peril or Promise? from the World Economic Forum estimated that by 2050 two billion people in the world will be over 60 years of age, that is, one in five compared with one in 10 today. A similar increase in the number of elderly people, that is, almost twice as many as today, is projected for the population of the EU by 2060.

A population growing older

A combination of low fertility rates and increasing life expectancy has resulted in the ageing of the European population. The Nordic countries have relatively high fertility rates compared with many other European countries such as Spain, Germany and Portugal. In 2011, fertility rates in the Nordic countries ranged from 1.75 children per woman in Denmark to 2.02 in Iceland (data by Eurostat). This may be compared with the European Union average of 1.57 and significantly lower birth rates in Spain and Germany (1.36) and in Hungary (1.23). Only Ireland scores higher than Iceland in Europe. However, the current fertility rates are not sufficient to compensate for a rapidly ageing population, especially in rural and peripheral areas with outmigration of younger people.

In the Nordic countries, the highest proportion of elderly people aged 65 years and over is found in Finland and Sweden. As in all the Nordic countries, the most notable differences between age groups are found between regions and municipalities. The general pattern is that the population in urban areas is younger than that in rural and peripheral areas, which is a pattern that is strengthened by depopulation in many rural areas. The proportion of elderly people is not only increasing in all Nordic regions but the process is continuing faster than ever before. The circumstances of the Nordic countries are different. While the generally older age structure has the largest potential impact on the welfare burden in rural areas of Finland and Sweden, the relative increase of the elderly population is actually greatest in Iceland, Greenland and in the commuting areas of Copenhagen and Helsinki, namely in the regions where the age structure is at present young.

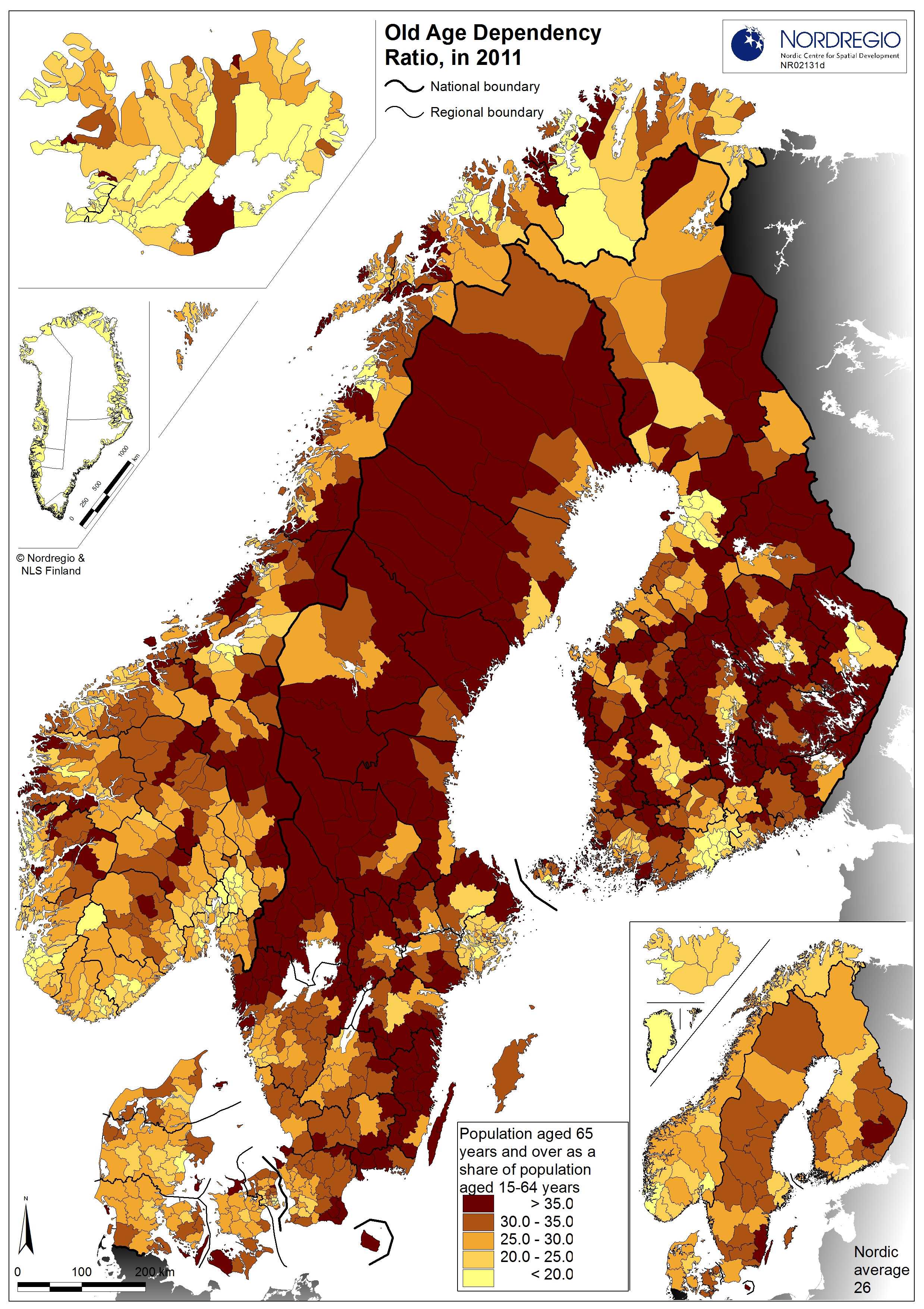

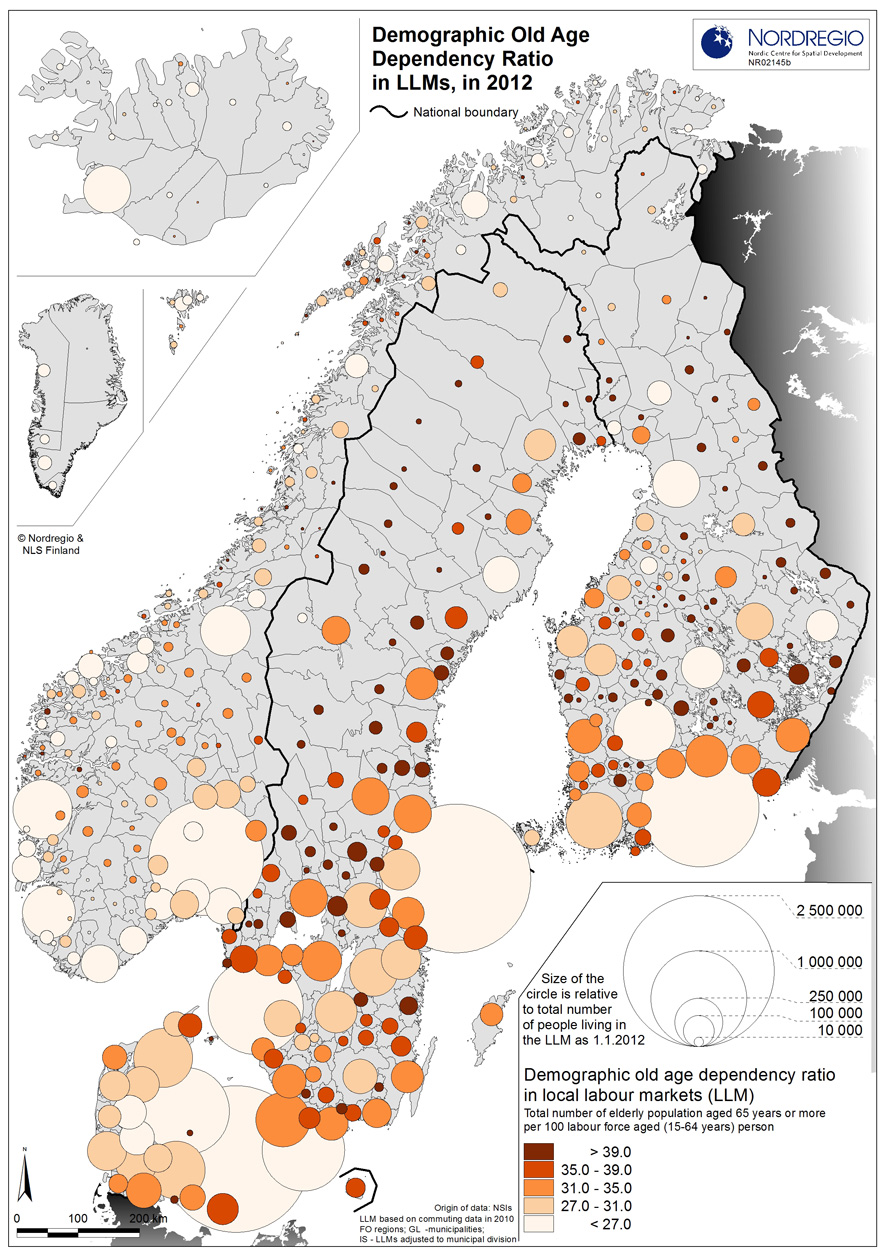

The demographic old age dependency ratio shows the number of people aged 65 years and over as a proportion of the number of people aged between 15 and 64 (Maps 1 & 2) and thus relates the proportion of elderly people to those seen as working aged people. The higher the proportion, the larger the dependency burden on people who are potentially in the labour market. In 2012, there were on average 26 people aged 65 and over for every 100 people aged 15 to 64, compared with 24 people 10 years ago.

Map 1 Population aged 65 years or more as a share of population aged 15-64 years.

Map 2 Population aged 65 years or more as a share of population aged 15-64 years in local labour markets.

The impact of an ageing population is not only relevant to the current generation of elderly people, but even more to the fast-growing group who will retire in future years. The 55–64 age group in the Nordic countries is larger than in the rest of Europe, which means that the number of people reaching retirement age will grow significantly in coming years. This situation is especially noticeable in northern and eastern Finland.

As an indication of the size of the future labour force, the group of people approaching retirement can be compared with those entering the labour market. In the Nordic countries, the generation entering the labour market is relatively large and together with increases in productivity could be large enough to compensate for the coming number of retirees, although in practice this is only possible in urban areas.

Impacts of demographic changes

Attitudes and policy debates on population ageing can be described as rather ambivalent. Increased life expectancy in combination with healthier and more active elderly years can be seen as a triumph of human development and the social capital of elderly people is without doubt a resource. At the same time, the increasing proportion of the elderly in the population is often seen as a peril or threat because of the costs associated with these dependent people; this process has become apparent in the vocabulary with terms such as 'agequake' and 'grey tsunami'.

In fact, in current policy debates, the ageing of the population is especially seen as an economic challenge, with one of the main challenges being the financing and securing of good-quality welfare services. An ageing population is assumed to increase demand for health and elderly care and to increase the burden on the pension system. In regions and municipalities with few young people and negative population change, it also means that the tax base is diminishing and fewer people are available to work in fields such as health and elderly care. At the same time, the decreasing proportion of children affects the other end of welfare services, because it becomes challenging to offer good educational opportunities, especially in smaller municipalities.

Awareness of the impacts that these population changes have, and will continue to have, on various policy areas is relatively high among policymakers at all levels. Measures and initiatives are being taken to address the issues. It is, however, a topic of discussion whether these initiatives are always appropriate, and especially whether they will address the long-term effects of population ageing.

Seeing elderly people as a resource

National governments in the Nordic countries have addressed the challenge of the ageing population through measures such as reforms of the pension system. National governments are addressing the challenge of a smaller labour force because of an ageing population by taking initiatives to improve working conditions, enhance labour immigration and increase various forms of co-operation in organizing welfare services.

The need to extend both ends of labour careers is often underlined in national policy debates. Raising the retirement age is being debated in all the Nordic countries. At present, the statutory retirement age in the Nordic Countries varies between 61 and 68, depending on the country and profession. The average exit age varies between 61.7 years in Finland and 64.8 years in Iceland (2010 data by Eurostat). Therefore the issue not only concerns increasing the statutory retirement age to keep people in the labour market longer, but also to attract people to stay in the labour market until that age. This is an issue where factors such as improved working conditions and flexible work-time could motivate people to work longer in their later years.

Making the labour markets more inclusive for all

It is also often highlighted that in the future young people will have to enter the labour market earlier than they do today to secure the financing and efficiency of the welfare system. This issue is often connected to the efficiency of the education system, but also increasingly to the challenge of high youth unemployment, especially in Sweden and to some extent in Finland. Another way to address the potential dearth of workers is better inclusion of marginal groups, especially long-term unemployed and people outside the labour force.

Immigration to the Nordic Countries is partly compensating for the national decreases in labour-force-aged population, but the immigrant work-force could be better utilized. During the period 2006–2010, a vast majority of Nordic municipalities had positive international migration. A more inclusive approach and initiatives to facilitate the entry of migrants to the labour market and integration into society are very often highlighted as solutions for the lack of labour and needed skills, especially in smaller rural and peripheral municipalities.

Remember that you are not alone

Inter-municipal co-operation is already a common strategy in the Nordic countries to provide good-quality welfare services of various types, despite higher demand and a diminishing local tax base. Municipalities co-operate to reduce costs and increase efficiency in welfare service provision. In addition, technical and e-health solutions, particularly in rural and peripheral areas, are frequently used and are under continuous development.

In border regions, especially in peripheral and rural areas, co-operation across national borders can compensate for the lack of critical mass of people to maintain good-quality welfare services. In the border area of northern Finland and northern Sweden, there are examples of cross-border co-operation in primary health care to facilitate the provision of health care for citizens on the other side of the border. To facilitate commuting to work across a national border, several initiatives have been undertaken in the Nordic countries, such as service points providing information on job-seeking, labour rights and social services. For example, the Öresund direkt service point in Malmö in southern Sweden started providing information for commuters in the Öresund area over 10 years ago. Since then, similar service points have opened to provide information for people commuting between Sweden and Norway and between Finland and Sweden. There are also other examples of cross-border co-operation and exchange of experience of labour force provision, housing, schooling and tourism.

Finally, it can be added that there is a need for policy initiatives at all levels of government to address the challenges and opportunities of an ageing population more efficiently. In addition, initiatives within various policy areas must be better co-ordinated and integrated. This article has also emphasized that because of large territorial differences in terms of demographic development, and ageing in particular, initiatives and measures need to be adjusted to different territorial contexts.

Back to Nordregio News Issue 3, 2013