In reality however while a burst of labour immigration to such rural and peripheral regions would, in theory, probably solve these problems such an occurrence is extremely unlikely to occur, at least in the vast majority of regions where the above-mentioned problems persist. Why is this so? "old" immigrants tend to cluster around the metropolitan areas and in major cities, while "new" immigrants head for the same regions. This allocation of immigrants is not optimal for the receiving countries.

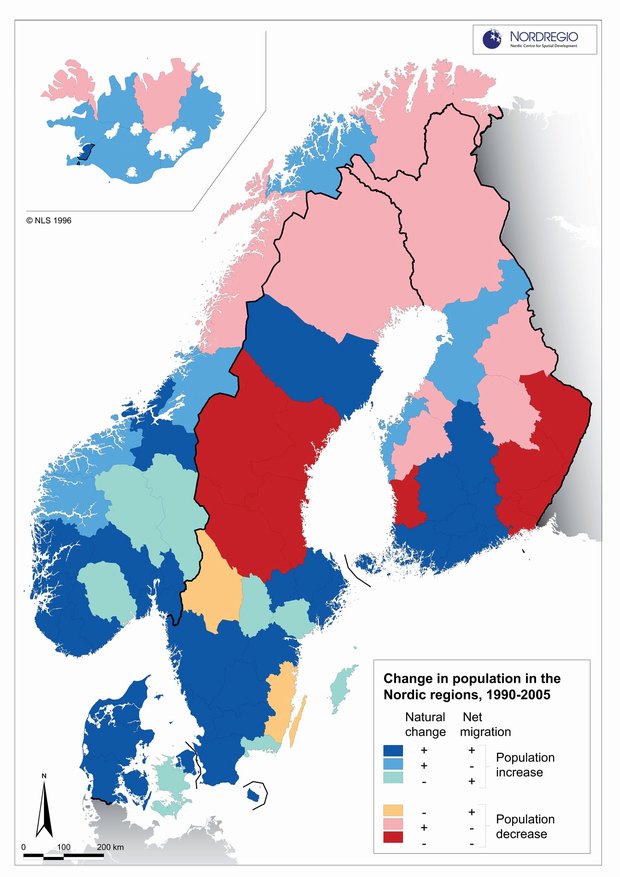

During the last 10 years regional demographic imbalances have consolidated in the Nordic countries. The capital cities and major towns have increased their population significantly while sparsely populated areas have been drained of people. Two out of three Nordic regions have thus seen a negative net domestic migration rate in recent years. Most of the Nordic capitals have a high rate of nativity which can, to some extent, be explained by a higher share of immigrants and a higher share of women of fertile age.

At the same time small and peripheral communities are steadily "greying". Compared to the development in the inner parts of Finland and Sweden, where pensioners and persons in the upper working ages dominate the population, this "greying" in Danish and Norwegian peripheries is however relatively modest.

This uneven population development puts significant pressure on some parts of the service sector: the population must have reasonable access to e.g. elderly and child care, medical and health care as well as schools whether or not they live in a metropolitan area or in the rural periphery. In addition public transport must function at an adequate level while the road system must be maintained across all regions.

The metropolitan-area population increase across the Nordic countries has created a situation where the demand for elderly and child care, medical and health care and schooling is higher in these areas than the available supply. In many Finnish and Swedish regions it is already difficult to find appropriate labour for e.g. elderly care or indeed for medical and health care positions more generally. This problem will only become more acute in future as more and more Nordic regions continue to "grey".

On top of this, the topology and the large travel distances experienced in the sparsely populated parts of the Nordic countries mean that access to e.g. medical and health care will always remain limited – to be 100 km distant from the nearest hospital makes it difficult to use medical services, particularly if the person concerned is elderly or has to rely on public transport. Without government subsidises from "richer" regions it would be impossible to maintain accessibility in these rural and peripheral areas. The question of central government subsidies for rural accessibility to services is however a 'political' and not a 'clinical' ore and, as such, is not open to permanent resolution.

Since it is, in relative terms, easier to influence regional demographic development through migration than through changes in nativity and mortality rates, in-migration to these regions may appear to offer a solution to the trend towards "greying" and a shrinking population. By allocating a larger share of immigrants to these regions demographic pressure on metropolitan areas and larger cities, as well as peripheral areas, would, some argue, occur. Theoretically, while this may appear to be a wonderful idea, unfortunately, it does not work in reality.

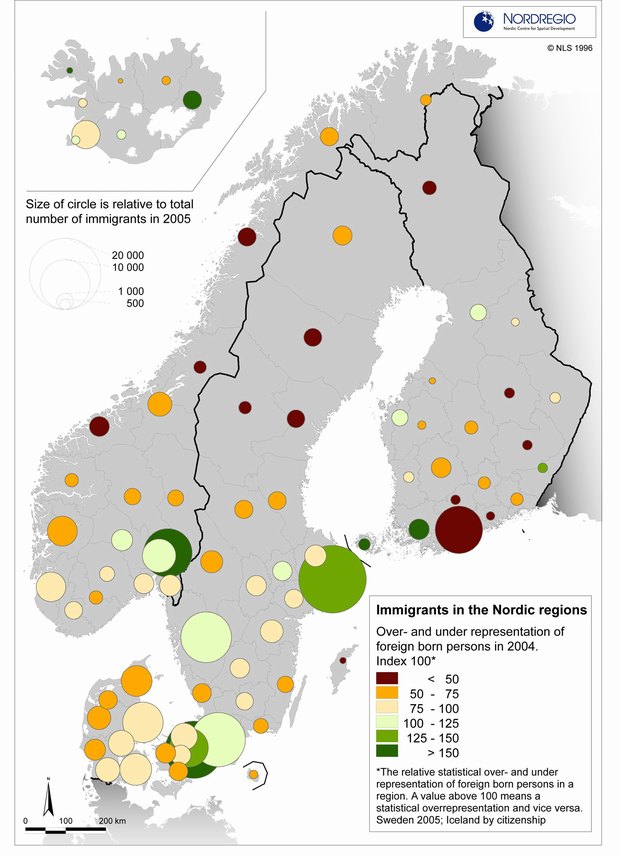

In Sweden, 62% of all new immigrants entering the country settle in the three metropolitan counties (Stockholm, Skåne and Västra Götaland). About 35% off all immigrants to Norway settle in the Oslo area with an additional 9% in Hordaland and 9% in Rogaland. Varsinais-Suomi and Pirkanmaa attract 8% each of the immigrants to Finland, while the Uusimaa region attracts 36%. In Denmark, the Copenhagen area attracted about 35% and the Aarhus area 13% of all immigrants to Denmark. The capital region of Iceland attracts 53% while the East region a further 23% of all immigrants. This indicates that the flow of immigrants does not favour the "greying" and peripheral regions.

Looking at the immigrants (flow) is one way of analysing immigration. Another way is to look at the number of foreign-born persons in a country (stock). By looking at the regional distribution of the total population and at the regional distribution of the foreign-born population it is possible to establish whether the foreign-born population is statistically over- or under-represented from a regional perspective.

The foreign-born population in Sweden is statistically over-represented in Stockholm, Skåne Västra Götaland and Västmanland, and in Norway they are statistically overrepresented in Akershus, Oslo and Buskerud. In Denmark the foreign-born population is statistically over-represented in only the Copenhagen area, while the foreign-born population in Finland is statistically over-represented in Uusimaa, Varsinais-Suomi, Etelä Karjala, Pohjanmaa and Åland.

In Iceland the foreign-born population is statistically highly over-represented in the East region, something that is undoubtedly a function of the building of heavy industries and power-stations in the area (See Journal of Nordregio No 2-07.), while, in addition, there is a small over-representation in the South, Southwest and Westfjord regions.

The underlying reason for the tendencies described above is the that the low productive and unqualified industrial jobs, the jobs that labour immigrants traditionally pick up, have disappeared due to structural transformation of the Nordic economics over the last 30 years. Metropolitan areas and major cities, with an expanding service sector, have thus become more important for economic growth.

Parallel to this process, the potential to substitute native labour with foreign immigrant labour has decreased. In the post-industrial society, labour and capital are complementary as compared to the industrial society where they substitute for each other. New technology and highly-skilled labour complement each other, which increases the segmentation process. This process is also regional in its character since different regions are distinguished by different economic structures. As a result, a regional labour shortage can occur even though unemployment remains high, which, in turn, creates an inter-regional as well as an intra-regional mismatch on the labour market.

What we are currently witnessing then is a situation where both refugees and labour immigrants head for the metropolitan areas and major cities of the Nordic countries – with one group targeting the low-skilled, marginally productive and unqualified jobs in the lower segment of the service sector and the other targeting high-skilled jobs.

There is then an obvious risk that the new immigration and settlement patterns will fuel – not alleviate – the already existing regional polarisation of the labour market if the mismatch on the labour market is further accentuated as a consequence of the regionally unequal distribution of jobs. This will then stimulate the concentration process once again rather than evening out the intra-regional concentration process.

By Daniel Rauhut, previous Senior Research Fellow at Nordregio