These tensions came to the fore in May 2013, when riots broke out in a number of suburbs in Stockholm. Numerous elements have been identified as contributing to the 10 days of unrest, which involved several hundred (predominantly) young people. There is little doubt that factors associated with poverty and social exclusion, including labour market access, urban development patterns and segregation, played a role.

As part of the ESPON TIPSE project, we explored the multidimensional and cross-sector issues of poverty and social exclusion, with a particular focus on urban segregation, in the Municipality of Botkyrka. Although Botkyrka continues to face problems associated with poverty and social exclusion, it became apparent during the course of the study that innovative policies and initiatives appear to be paying dividends. Concerted approaches from all levels of government are necessary to resolve these challenges, but this article focuses on steps undertaken in Botkyrka Municipality. In the following article in this issue, Evert Kroes from TMR elaborates on regional and national approaches. These efforts, which are mainly characterized as people-first and/or integrated across sectors, have relevance for other Nordic regions dealing with similar situations.

Botkyrka

Of the 26 municipalities in Stockholm County, Botkyrka had the lowest median income in 2010 and among the highest municipal concentrations of persons with a foreign background, in a county with one of the highest concentrations of persons with a foreign background in the country. Despite solid economic growth in the county, unemployment in Botkyrka remains higher than the county average.

View of Hallunda-Norsborg in Botkyrka.

At the submunicipal level, there is a strong north–south distinction in Botkyrka with respect to socio-economic status, demographics, transportation and built form. South Botkyrka is characterized by higher income and employment levels, as well as by a larger percentage of people with an ethnic Swedish background. The built environment predominantly consists of villas and smaller multifamily buildings, and with the overland train, the area has a more rapid connection to the city centre. North Botkyrka has a low median income and a very high percentage of persons with a foreign background. Most of the residential built forms are modernist high-rise buildings that were constructed during the Swedish Million Homes programme in the 1960s and 1970s. North Botkyrka is connected to the city centre via subway, which takes more time than the overland train. It is also important to note that there are only limited pedestrian, cyclist and public transit connections between North and South Botkyrka and even between districts within these respective areas. These mobility challenges, influenced by Stockholm's 'string of pearls' development strategy, limit the accessibility of centralized services in the municipality, leading to greater district competition for the municipality's scarce resources.

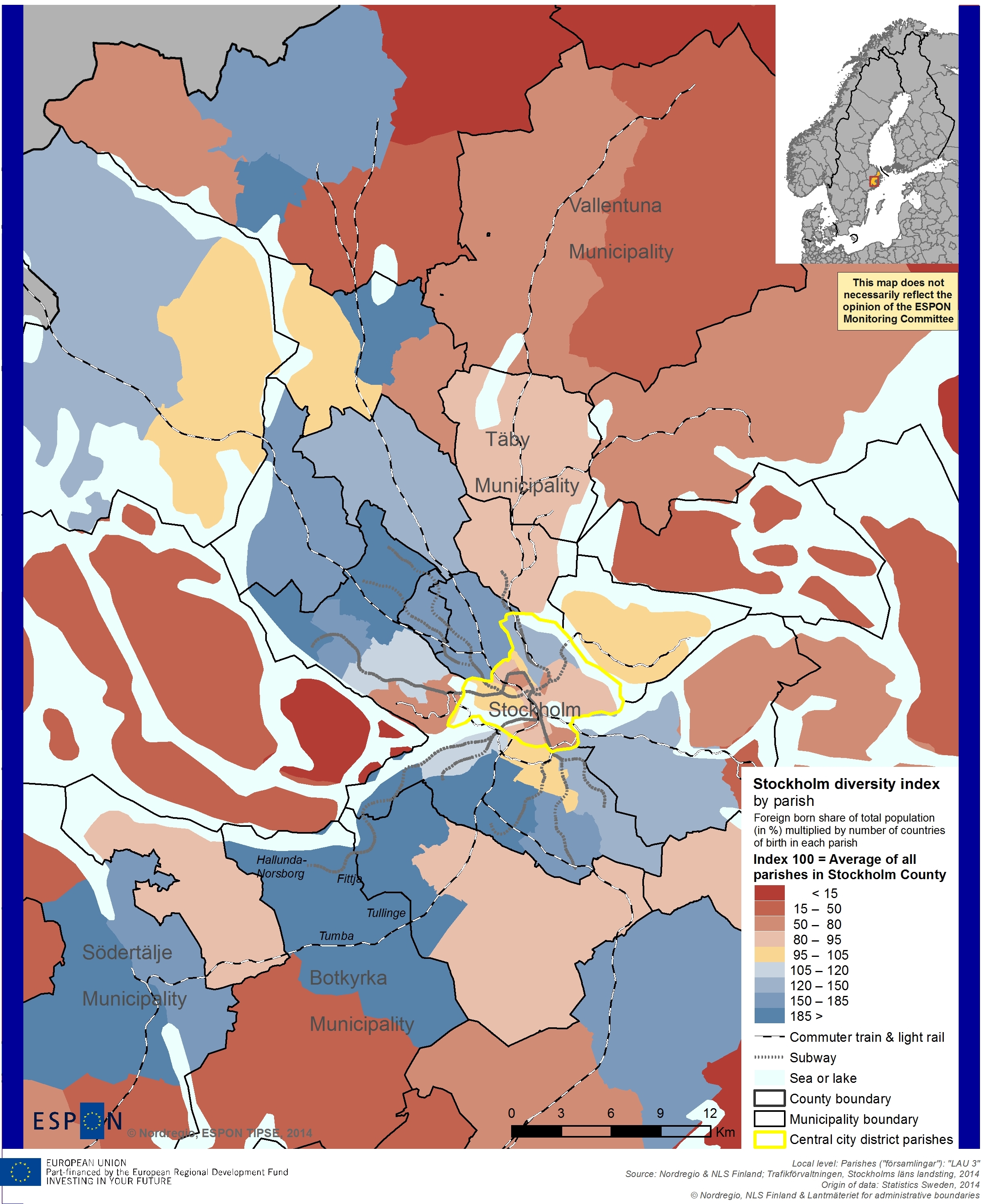

Botkyrka is a highly diverse municipality as can be seen in Map 1, where unlike many other cities, people with different foreign backgrounds tend to mix rather than to isolate themselves in clusters. To illustrate this mix we have developed a 'diversity index'. To create the index, the share of foreign born population by parish[x] was multiplied by the number of nationalities present in each parish in Stockholm County.[xx] Results were tabulated for all parishes within the County and the subsequent parish average was set to an index of 100.

As the map shows, North Botkyrka is one of the most diverse parishes in the Stockholm Region. Here, the populations of people with backgrounds from Iran, Iraq, Turkey, the 'Rest of Asia', Latin America and Africa all increased significantly between 1991 and 2001 in North Botkyrka.[3] There has also been notable growth from the 'Rest of Europe' (Non-Nordic, Polish or German). Botkyrka is also a global media hub for the Middle-Eastern Christian diaspora. In contrast to this diversity, there is a striking difference with respect to the presence of Swedes, which Hårsman described succinctly: "The ethnic variety increases when the fraction of the comparatively large Swedish group decreases."[4] With this in mind, it appears that more 'excluded' areas, such as North Botkyrka, are, in fact, quite diverse and inclusive, but the missing piece in this diversity puzzle is Swedes. However, areas with few ethnic Swedes also are often characterized by lower levels of education, employment, income and access to Swedish media at a regional scale.

Map 1. Source: Map developed by Linus Rispling, Nordregio, based on data from Statistics Sweden, 2014. Click to view larger image.

An Integrated Response that Puts People First

Recognizing the poverty and social exclusion challenges that it faced, Botkyrka Municipality has embarked on a wide-reaching and cross-sector strategy that centres on the well-being of the people who live in Botkyrka and celebrates their differences. Botkyrka is the first municipality in Sweden to promote interculturalism, an approach that respects different cultures and seeks to harness the strengths that these many different backgrounds offer. Botkyrka's approach to interculturalism focuses on the exchanges and interactions between people with different origins. It can be distinguished from the more familiar term 'multiculturalism', which implies a more passive strategy.[5] These cross-sector, people-first strategies are reflected in the work of the municipality's societal and spatial development unit, which integrates socio-economics, culture, physical planning, the environment, youth and community outreach, segregation and education. This also means that when a development project is proposed, its impact on the community is evaluated, as well as its impact on the environment. Through these approaches, the wide range of prospects for, and needs of, Botkyrka's residents is considered to a greater extent than is legally mandated.

Improving individual well-being is a complex issue, particularly in a diverse community. To enhance its capacity to reach a wide range of individuals, Botkyrka Municipality co-operates broadly with community groups. The Botkyrka Public Library in Hallunda is heavily involved in outreach efforts and continues to extend these efforts into the community. Notably, they recognize that learning takes place in many ways, and by recognizing the local residents' range of backgrounds, they place an equal emphasis on the spoken and written word. A degree of cultural understanding is also evident in the school system, where learning and outreach approaches, as well as language training opportunities for teachers, are intended to engage the community. The library also works closely with the Women's Resource Centre, a non-political organization that helps to integrate women (both newcomers and long-term residents) in Botkyrka into the work-force, with a particular focus on those who have been out of the labour market for extended periods of time. They offer training in desirable employment skills, guidance on how to start a small business, and Swedish language training that is more accessible for women in northern Botkyrka. There have also been strong efforts to engage young people through accessible sports, exchange programs and summer employment opportunities.

Positive Results

By simultaneously considering various elements that influence poverty and social exclusion, including social issues, the environment, labour market access, built form and mobility, Botkyrka Municipality is using its financial resources to respond to the challenges at hand. By focusing on the well-being of individuals, Botkyrka is trying to meet better the needs of its diverse population, which is underlined by its interculturalism strategy and wide range of community outreach initiatives. Botkyrka's focus on the well-being of its residents is further demonstrated by its strong co-operation with grass-roots and community groups, which facilitates targeted responses to specific challenges in financially effective ways.

There are a number of prominent indications that these efforts are having positive impacts on residents and fostering greater attachment to the area. Of the 30 municipalities with the highest rates of child poverty in Sweden, Botkyrka was one of only two where the trend was reversed and the rate declined between 2005 and 2010.[6] Furthermore, for the first time since the Million Homes Program, new dwellings are being built in North Botkyrka, and as illustrated by Fittja's Sjöterrassen development (which sold out in record time), they are in high demand. Finally, during the second night of disturbances during May 2013, the subway station in Fittja was heavily vandalized. In a poignant example of commitment to their community, and in an effort to dispel the myth that many local youth were involved in the unrest, 60 14- and 15-year-old students from Fittja (and their teachers) cleaned up the area. As one student, Dilnaza, said, "I felt angry and sad that people had destroyed and trashed things where I live. But it felt great that everyone was helping out to clean up all the glass, erase the ugly things they had written and make it look nice here again."[7] Although challenges persist, the Municipality's approach appears to be paying dividends.

[x] Parishes are sub districts to municipalities and are based on traditional settlements, where a church was at the centre, rather than being built on today's administrative borders or demarcated around today's developing nuclei. The reason why parishes are still used for demographic data is mainly because the state church until the 1990's was responsible for keeping track on births, marriages, etc. This implies that the geographic boundaries of parishes are still used. In this case, data availability was the central reason that the parish scale was used, as opposed to sub-district boundaries.

[xx] The data was captured on December 31st, 2013. For reasons of personal privacy Statistics Sweden has excluded data that fulfils one of the following two criteria. (1) The number of persons with a specific country of birth that is less than 20 in the whole county (2) The number of foreign born are less than 20 in the parish.

[1] OECD (2006) Territorial Reviews: Stockholm (OECD Observer). Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

[2] Stahre, U. (2004) City in Change: Globalization, Local Politics and Urban Movements in Contemporary Stockholm. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research: 28(1), pp. 68–85.

[3] Botkyrka municipality (2010b) Strategy for an intercultural Botkyrka. Accessed August 8th 2013.

[4] Sveriges Radio (2012, June 26) Barnfattigdomen ökar I utsatta kommuner. Accessed May 26, 2014.

[5] Chaaban, S. (2013, May 22) Students clean up Fittja. Metro. Accessed: May 22, 2013.

[6] Statistics Sweden (2013) Folkmängd efter region och tid. Accessed May 28th, 2013.

[7] Hårsman, B. (2006) Ethnic diversity and spatial segregation in the Stockholm region. Urban Studies, 43 (1341).

Back to Nordregio News Issue 3, 2014