From the fishing industry on Suderoy, Faroe Islands. Photo: Rasmus Ole Rasmussen

Both settings can be found, but the reality is that in the Arctic most communities have moved on from the traditional rural lifestyle embodied in the first image and adopted a lifestyle with more urbanised characteristics. So instead of closed, self-centred, and introverted communities, they have transformed themselves into more open and extrovert societies. By far the largest proportion of the population now works in the 'third' sector, providing public and private services to each other, for instance in relation to education, health care and social services.

These developments have also resulted in a situation where the traditional gender-based division of labour is disappearing, and is, step by step, being replaced by a situation where the social and economic role of the inhabitants is increasingly determined by individual interest and qualification. A shift is therefore occuring from structured hierarchy where males and elders have been decisive, to a situation with a much higher degree of hierarchical indepen-dence, where the decisions taken are based much more on aspirations, indi-vidual skills and knowledge.

Female flight

One consequence of these changes is the emergence of a situation where more females consider, and also now tend, to migrate permanently away from their home community and region. A first step in this process may be to move from smaller to larger places (within the region) with better opportunities better fitting their qualifications, and also providing potential employment outside the realm of the traditional economic activities undertaken in the communities.

Gender-based differences in migration choice are nothing new in the Arctic. In connection with large scale resource development projects, young and middle-aged males in search of employment and income opportunities have chosen to become migrant workers, leaving their communities for either a shorter or a longer period of time in the process. Seldom, however, have they left the community permanently. Only if the job turned out to be more permanent in character, and generated substantial incomes, have they done so. Often in such cases moreover they arrange with their families to follow them and settle in the new town or village.

Females, however, seem to migrate more permanently. Moreover, such choices have significant implications for the communities they leave, for instance decreasing opportunities for marriage, the maintenance of family life and family structures, and also fundamentally influencing other cultural activities.

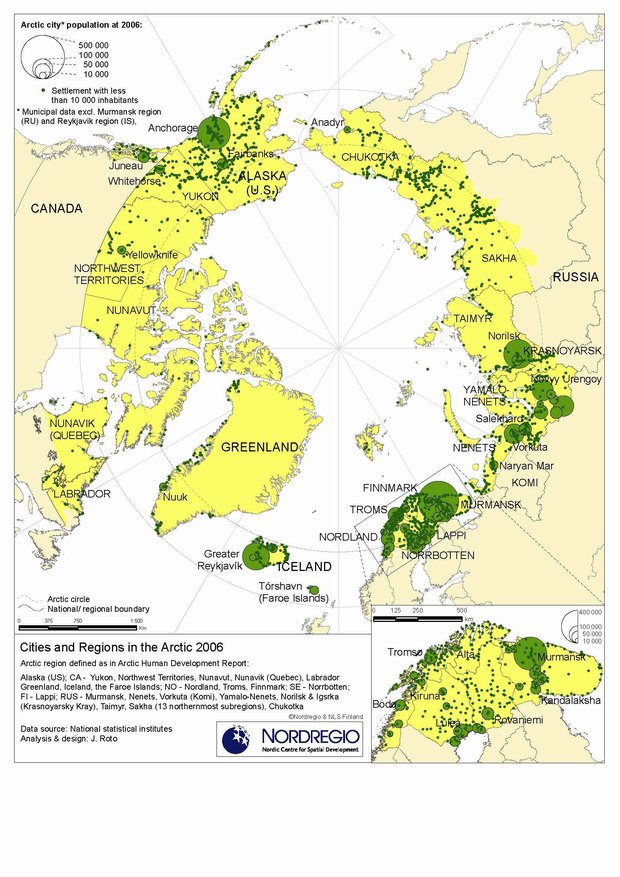

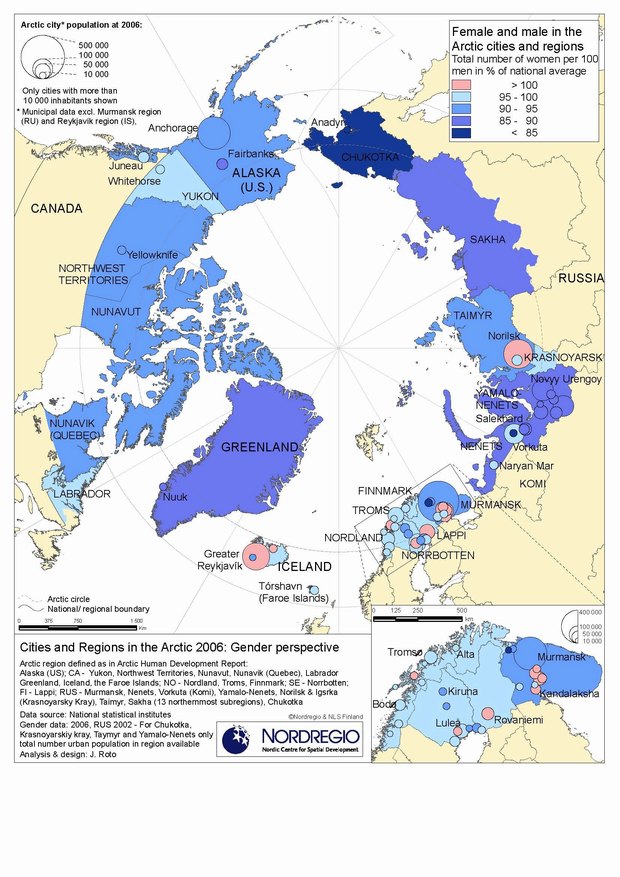

Canada and USA

In Canada the national average shows that there are 103 females for every 100 males, a level which is comparable to most countries in Western Europe and North America, and is due to women generally living 5-10 years longer than men. Moving to the northern part of the country, this pattern however changes markedly. In Nunavut, for instance, there are only 95 women for every 100 men, so the level is as low as 92% of the national level. Similarly the Yukon level is at 96%, Nunavik at 92%, Labrador at 98% and North West Territories at 92% of the national level.

In USA the national level is at 103 females per 100 men, but Alaska shows a female ratio as low as 90% of this, meaning that just 93 females exist for every 100 males. Looking at regional differences Kodiak Island and North Slope are at around this level, while the urban centres show a higher proportion of women – Anchorage 98% and Fairbanks 94% respectively. The Valdez-Cordova region, however, is at 89%, Bristol at 85%, and the Aleutians as low as 51% and 55% for East and West respectively.

Russia

The Second World War still has a significant impact on the population structure in Russia. In 1950 six out of 10 persons were females, and even today there are 115 females for every 100 males in Russia. As a consequence the relative proportion of females is generally at a higher level in the Russian North when taken in absolute terms. Compared to the national level, the relative proportion of females however turns out to be at an extremely low level.

Taken in absolute terms, the urban and western regions like Murmansk Oblast, Krasnoarskiy Krai and Nenetskiy Autonomous Okrug show a small surplus of women, somewhere between 104-110 females for each 100 males. But compared to the national average a clear deficit appears, at a level around 92 to 95% of the national average. Moving eastwards, the levels decline dramatically, down to 80-85% of the national average with the far eastern Chukotskiy Autonomous Okrug as low as 79% with an absolute value of 90 females per 100 males.

The Nordic Countries

In the Nordic countries the levels of women to men show national averages of around 103 to 111 females per 100 males, with Finland having the highest level, and as with Russia the Second World War is responsible for this deviation from the general Nordic Patten.

The northern regions of the Nordic countries show the same pattern as the rest of the Circumpolar North. At the regional level the "North calotte" area shows numbers around 95 to 98% of the national levels, but with the Faroe Islands down to 92% and with Greenland having as low as 88 females per 100 males. Looking at the municipal level many Northern and interior municipalities turn out to have less than 80 females for every 100 males.

Affinity to change

The most likely explanations for the changes described above are connected to two interrelated factors. On the one hand to the labour market characteristics and job opportunities offered, and on the other to a number of gender-related differences in aspirations and approaches to change.

The perception of northern communities as "frontiers" in the North has profound implications for the kind of business development focussed on, as well as the job opportunities offered. The North as a provider of raw materials is a development trademark while renewable resource cultivation activities – hunting, fishing, reindeer herding – as well as the harvesting of non-renewable resources – the large scale extraction of minerals and energy resources - each continue to predominantly offer what can be viewed as male jobs. Fisheries used to offer on-shore jobs to women in the fishing industry, but most of these processing jobs have been moved on-board to the factory trawlers themselves. The development of advanced technology and the automation of the labour force reduce the need for manual production, and job opportunities are thus declining.

The gender-related perception of custo-mary male activities related to resource exploitation seems to be "sticky", in the sense that males have difficulty in moving on from what once were key activities, but now constitute only a small percentage of the available jobs. Females, however, seem less limited by specific job characteristics, determined by what may be considered to be "traditional" and "acceptable" activities.

Gender differences in adaptation to change become very clear when talking about the changes needed in respect of the "knowledge economy", where education has become a keyword. Today more females than males in all of the Nordic countries finish higher education courses, and fill the majority of positions in administrative and service-related public and private business activities. The shift from male to female dominance appeared in the late 1990s, and in a total of more than 1500 municipalities in the Nordic countries, there are only more educated males than females in a handful of cases.

The further north you go the more marked the differences appear. In Greenland three out of five persons getting a degree or diploma will be female. Boys still dominated the educational system up until around 1990 with 5-10% more boys than girls finishing a diploma or degree-level course of education. From 1991, however, a marked change occurred. During the 1990s and into the first half of the 2000s, between 10 and 20% more girls than boys finished an education, and since 2003 more than 60% of the persons graduating have been female. So from a situation where women were merely 'accepted' in the education system, they today have become the key persons ensuring that society as a whole gains the qualifications needed. This is not only a situation characterizing the Nordic countries, but a pattern found in the whole Circumpolar north – and a general trend in most of the industrialized world.

Who are the providers?

While resource exploitation is still viewed as the main economic basis for communities in the North, the reality is that the third sector – the service sector with wage work in administration, education, the social services etc., – has become the main income source for most families. With limited job opportunities for well educated women, however, the prospect of staying remains highly unattractive for many women, resulting in continuing out-migration as more or less the only option available to them.

For many men, however, limited options exist in respect of them leaving their current occupations. In the small villages in particular the situation is often desperate. Without proper qualifications unskilled jobs becomes the only option, and as these are also now disappearing, the prognosis for unskilled male employment is becoming ever bleaker. They are caught in a classic "catch 22" situation where their incomes from traditional activities are not enough to enable them to profitably continue in work, as these limited incomes do not enable them to re-invest in new equipment in order to expand their activities.

They also have difficulty in finding young girls who are interested in staying in the village, thereby severely limiting the option of generating the double incomes which are needed in order to maintain a life encompassing traditional activities. And without skills and money it is not possible to move to larger places to find a job. This situation then sees many in the villages, but also some in the towns, in desperate straights often resulting in violence and abuse, which only adds to female flight, not only in order to pursue a better future, but also to avoid the negative consequences of the process of decline.

The villages are the first to be abandoned, though the smaller towns are now also suffering from female flight. Only the towns with higher education opportunities and a broader supply of qualified job opportunities seem to be able to maintain an environment which seems to be attractive enough for younger women to enjoy.

Selected reading on the topic

Bjerregaard P, Holm AL, Olesen I, Schnor O, Niclasen B. Ivaaq (2007) "The Greenland Inuit child cohort: a preliminary report. 2007". National Institute of Public Health. Copenhagen.

Hamilton, L.C., Seyfrit, C.L. (1993) "Town-village contrasts in Arctic youth aspirations", Arctic 46(3):255-263.

Hamilton, L.C., Seyfrit, C.L. (1994) "Female Flight? Gender Balance and Out-migration by Native Alaskan Villagers". Arctic Medical Research, vol. 53: Suppl. 2, pp.189-193

Hamilton, L.C., Rasmussen, R.O., Flanders, N.E., Seyfrit, C.L.(1995): "Out-migration and Gender Balance in Greenland". American Journal of Sociology.

Rasmussen, R. O. (2004) "Socio-economic consequences of large scale resource development; cases of mining in Greenland", in: Beyond Boom and Bust in the Circumpolar North (pp. 101-131). Prince George, B.C., Canada: UNBC Press

Rasmussen, R.O. (2007) "Gender and Generation Perspectives on Arctic Communities in Transition". Knowledge and Power in the Arctic. Arctic Centre, Rovaniemi.

Tommasini, D and Rasmussen, RO (2006) "Adapting to change: cases of detached, dependent and sustained community development in Greenland. AAAS 2006 Arctic Science Conference, Fairbanks, Alaska.