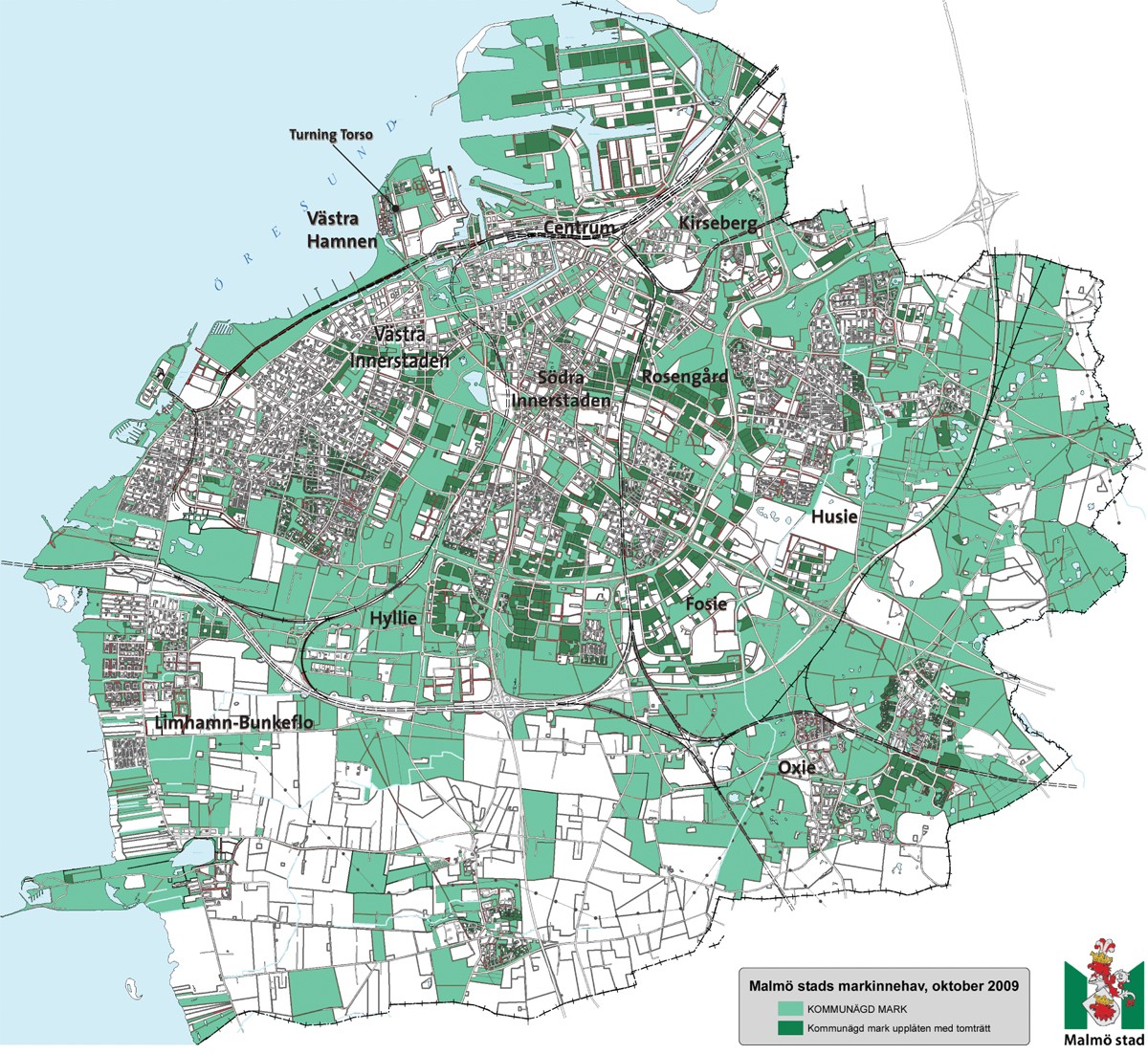

Above aerial photo of Malmö. Picture from the City of Malmö. The white tower is the Turning Tower. On map below: Green areas are owned by the Municipality.White indicates predominately private (or state) ownership. Provided by Malmö Fastighetskontor.

To put carbon neutrality into practice and make it sustainable does not however simply mean exchanging out of carbon-based sources of energy. Energy consumption also has to decrease, many argue. In new and old buildings alike this is visible in at least two ways. The buildings should consume as little energy as possible, and preferably actually store energy; and the inhabitants should limit their energy consumption. What then does Malmö's road to carbon neutrality look like?

The public housing corporation Malmö Kommunala Bostadsföretag (MKB) is, with its 22000 apartments, Malmö's largest provider of rental property. As a municipal company it has the role and the responsibility of realising public visions. Since 2008 MKB has only used wind-powered electricity and in the same year the first solar cell installation was set up to test a new technique for self-support.

In planning both the Western Harbour and the newer Hyllievång area, the national template dialogue, held between the local government and the building proprietors (ByggaBo-dialogen) was employed. Addressing the basic issues of sustainability, the purpose of this model is to construct a national sustainable construction and housing sector by 2025. Within areas such as architecture, green spaces and low energy consumption, the focus is on reaping high rewards at feasible costs.

Put forward as the national example of sustainable urban planning, the most common illustrations of its climate smartness are panoramic views of these two newly developed areas. But with most of the city's apartment blocks built after the Second World War the majority of the city's inhabitants live elsewhere.

In already built areas other forms of dialogue are taking place. In Rosengård, home to somewhat less than 10% of Malmö's population, a local stakeholder dialogue on sustainability was completed last year. The area has a high level of energy consumption and the goal of the City is now to provide Rosengård with entirely renewable energy by 2015.

One strategy is to make the flows of energy more visible by using sun panels, solar cells and urban wind mills thus moving the production of energy closer to the inhabitant. (The same strategy is applied in new areas under development in the Western Harbour). This stakeholder dialogue model is soon to be replicated in other parts of the city.

From the ground, the most visible example thus far of urban sustainability measures in already built areas is the eco-city of Augustenborg. Located south-east of the city centre, it is known for its green and blue adaptation measures such as green roofs and open surface water management. These tools are not only adaptive, but also control the flows of energy through insulation and heat storage. In this neighbourhood the focus on citizen involvement has been strong, providing the inhabitants with 'know-how' and support for their own initiatives.

Many large actors in the construction business are now putting energy streamlining and climate responsiveness at the forefront of their construction agendas. With shared visions and explicit environmental policies, private actors seek their share of the market.

The 'passive house standard' is one alternative here. In the new development area in the Western Harbour the ambition is that one third of the projects are built with a passive house standard and the remaining two thirds built as low energy houses (a total yearly energy consumption of 45 kWh/m2 and 65 kWh/m2 respectively, the nationally recommended level is 110 kWh/m2).

South-east of the city centre is the residential area of Tygelsjö. The construction company Skanska and furniture giant Ikea will soon start building apartments within the common endeavour BoKlok. As with most new developments the focus here is on sustainability and cutting carbon emissions is a priority in the project description. One important pillar in BoKlok is the aim that individual residential units are "affordable for the single mother with one child". To reach this target, buildings are factory-made in big volumes.

Between 1965 and 1975, large residential developments were built in the context of the national Miljonprogrammen ("the Million Programmes"). In the city of Malmö Almost 22 000 apartments were built during this period. Renovating these is one local government approach to unifying all parts of the city and making these residential units both attractive and sustainable.

More recently, the reconstruction of some of these often very high energy consuming houses into passive houses has gained in support. There are already a number of good examples of this in the Gothenburg area (see Journal of Nordregio 2/2008).

The city of Malmö, together with the Institute for Sustainable Urban Development (ISU) among others is currently increasing the options for small and medium-sized construction companies in the region to develop sustainable solutions for postwar housing areas through the EU project ERUF EKO (Ecological Restructuring of Buildings of the Postwar Era). Alternatives in respect of climate responsive solutions are under evaluation in an apartment block in southern central Malmö. These include self-regulation of ventilation, heat and water.

Increased partnership and dialogue hold the potential to bridge ideal visions and real politics. Following the explicit intent of the city of Malmö, will these initiatives become mainstreamed rather than remaining only as a list of good examples? To make the goal of carbon neutrality sustainable in its broadest sense, combining the climate responsiveness of the market-oriented building proprietors and the local development of ecologically sustainable practices and solutions, may well become a necessity in all areas alike.

Above aerial photo of Malmö. Picture from the City of Malmö. The white tower is the Turning Tower. On map below: Green areas are owned by the Municipality.White indicates predominately private (or state) ownership. Provided by Malmö Fastighetskontor.

By Tanja Ståhle, former Research Assistant, Nordregio