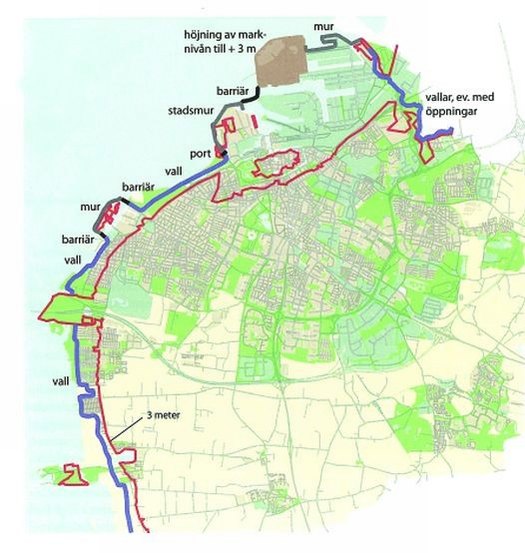

Västra Hamnen in Malmö with the Turning Torso.Will there be a wall to protect the seafront from rising sea-levels? Photo provided by the Municipality of Malmö.

Citizens constitute the city's backbone. Preferably they will have the choice to live and dwell in a climate-friendly and sustainable way. That makes the development of housing areas a significant challenge for physical planners. Neither spatial nor economic resources are unlimited however.

In coastal areas the threat of rising sea levels will in many cases contribute to less land being available for housing or for recreation and economic activity while less affluent areas may simply lack the resources to offer a sustainable choice.

In this context two important questions have to be raised: What are the challenges for housing development from a climate responsive and sustainable urban planning point of view? And, will the choice of climate responsive and eco-friendly living be available for all?

With approximately 290 000 inhabitants, Malmö is located in the heart of the dynamic Öresund region. This coastal city is renowned for its green parks, its bicycle-friendliness and its 43 kilometres of coastline. Formerly known as a heavy industry town with the Kockums wharf as its pounding engine, central Malmö is the site of a recent visual transition. The building projects in Västra Hamnen (Western Harbour), site of the Santiago Calatrava-designed landmark 'Turning Torso', have transformed the character and usage of the extensive harbour area.

East-west division

Moreover, as cities often are, Malmö is a heterogeneous place. The multiethnic diversity and differences in socioeconomic affluence is in Malmö geographically stratified along an east-west partition. The same goes not only for the character but also the quality of urban housing. Of Malmö's 146 000 dwellings, 82% consist of apartment blocks and the remaining 18% of self contained houses. The population is growing and in some parts of the city, household density is increasing above levels of what is already defined as 'confined living conditions'. Regardless of ambitions and detailed planning, last year less than 500 new housing construction works were initiated, partly due to the recession.

Therefore, not only from a planning perspective but also from the perspective of fairness in social and economic sustainability, the political goal of urban eco-sustainability and climate-sensitive housing development is under pressure to translate into real political solutions.

All parties say yes to densification

Among all political parties the political vision for spatial growth in Malmö is urban densification. Building the compact city has become a solution that is sensitive to citizens' preferences for the traditional multifunctional city structure and reflective of the reluctance to exploit the surrounding fertile farmland.

However, areas attractive for conversion, such as the old harbour areas or other industrial grounds, are close to the coastline and often located lower than three metres above sea level. Other attractive areas are located along the low-lying south-western coast. These areas are potentially subject to the same problems of flooding and storm surges and often consist of fertile agricultural land.

The municipal commissioner of urban planning the social-democrat Anders Rubin argues that with the current population increase of approximately 7000 people a year, urban densification of the already-built environment may not be enough and that some rural land has to be claimed. Talking about built area densification in the outskirts of the municipality the aim would be to build close to public transport networks. - With a normal population increase, the discussion would have been different, he says.

In already developed areas densification could pose a significant problem. Citizens may want to protect their open spaces and functionality opportunities might be constrained by earlier detailed planning.

Who shall pay?

The general development plan limits new construction work to areas more than 2.5 metres above sea level. Whereas a one metre increase in the sea level would put an area of 229 ha at risk, threatening the modest number of 20 taxation units, a 2.5 metre increase however raises the numbers to 1392 ha and 1820 units respectively. A scenario seeing an increase of 3 metres almost doubles these numbers.

The city of Malmö estimates that in current scenarios, anticipated problems are manageable through coastal protection by earthworks, walls and sea barriers. One issue yet to be dealt with however is that of cost.

- Legally it is the property owners who have the overall responsibility for their properties and formally the municipality cannot of course be responsible for an increase in the sea-level although we are planning counter measures. At some stage also the regional- and state-authorities will have the get involved, but when or where as yet remains unclear, says Anders Rubin.

Most property buyers are nevertheless putting their faith in the hope that potential problems will be taken care of by the authorities. The risk of flooding or run off is a question very seldom raised in negotiations, as pointed out by two separate private actors; real estate agent Håkan Sköld and the national representative for Skanska/BoKlok, Ulrika Norborg.

In spite of the potentially quite threatening picture, buyers in general are not really thinking about the exposure. - There is a clear expectation that the public purse will pay for efforts in the shape of embankments and other forms of protection, Håkan Sköld pronounces. This can be further illustrated by the long waiting list for individual building sites in western Malmö, also in the coastal zone. There, the average housing price is also about 30% higher.

Is climate responsiveness for all?

One conclusion seems obvious: it is not the effects of climate change in themselves that are driving spatial development. Speaking visions and determination, there is no doubt that urban spatial planning in the city of Malmö is at the forefront both in terms of climate responsiveness and ecological sustainability.

Nevertheless, when developing climate-friendly housing and marketing eco-sustainability, attractiveness such as closeness to coastal recreation areas provides a strong incentive. The capacity to pay is fundamental to the system. In attractive areas the market through the paying customers is a strong driver. This leaves the less attractive areas to be more dependent on the individual as a tax-payer, which in the long run may make room for different solutions and more deliberative approaches.

The most expensive climate change adaptation measure will probably be the safeguarding of the coastline. What if sea-levels rise above the manageable one metre level? Will resources be taken from the more needy eastern parts of the city to protect those in more affluent areas?

Anders Rubin argues however that it is not only Malmö that will have problems if the rise in sea-levels reaches three metres. - If this were to occur, national needs would revail over local needs , and the whole thing would become a question for the state rather than the municipality.

All in all then, while climate responsiveness is in many respects driven by economic interests a basic level of insecurity remains in respect of who will pay. If the emphasis turns out to be on individual responsibility, other measures regarding availability, choice and influence are needed so as not to consolidate social and economic segregation.

Therefore, synchronizing space, time and resources still poses a challenge for the city of Malmö in achieving eco-sustainable livelihood options for all.

By Tanja Ståhle, former Research Assistant, Nordregio