Myggedalen in Nuuk provides a typical example of the rapid growth of the private housing market in the Arctic. Photo: Minna Riska

Urbanisation is a global trend which will contribute significantly to the future shaping of human life. Half of the world's population now lives in urban areas, drawing most of their food and natural resources from the surrounding rural areas. By 2050 it is estimated that eight out of ten of the world's people will live in cities.

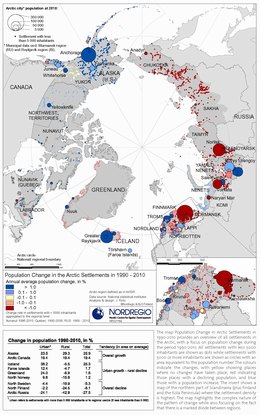

The trend is similar in the Arctic. Most of the population growth experienced in the Arctic occurs in urban centres, is tied to new economic activities, and contributes to a re-structuring of the settlement pattern that will continue for decades to come.

In parts of the Arctic a high birth rate has compensated for the general pattern of outmigration from the smaller settlements, for instance in parts of Arctic Canada and Alaska. It is however just a question of time until the patterns here will resemble those in the rest of the Arctic. Birth rates are declining, the level of outmigration remains high and the smaller settlements are becoming even smaller while the larger settlements are growing. While differences used to exist in the choice of settlements between the indigenous and non-indigenous populations, the current trend of concentration in urban settings has now become common for both groups.

People move for many reasons, often attracted by the promise of work, higher salaries and a better social life, as urban areas usually offer better opportunities, a diversity of economic activities and more options for education and social networks. At the same time cities are often characterised by social stratification. While they can be viewed as hubs in the economic development of their regions they also potentially foster social inequality.

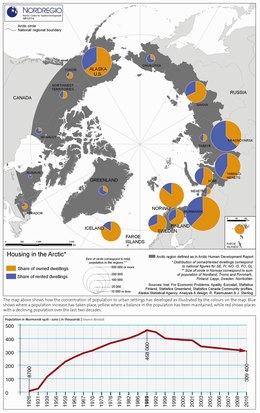

In most parts of the Arctic the public sector still tends to dominate in respect of responsibility for housing. The historical reasons for this vary and include geopolitical considerations, colonial characteristics, regional policies etc., but the consequences have been quite similar; a large public sector with the state and regional authorities involved in most regulation and planning measures.

In Iceland and the Faroe Islands private ownership has generally predominated, and only recently - as a consequence of the economic crises and the problem of ensuring that affordable housing is made available for the new generation – publically owned houses and dwellings for rent have become more common.

In other parts of the Arctic, the privatisation of the public sector housing market has been ongoing since the 1990s. The case of Greenland is illustrative here as indeed is that of Russia, where the shift from public to private housing has developed with unprecedented speed over the last decade or so.

One of the major rationales for this has been the possibility of using the housing sector as a way of establishing local wealth that enables both individuals and communities to be more independent in relation to the development of activities requiring investment. At the same time it adds to the place-based ties which may contribute to a more stable situation with regard to both job opportunities and demographics.

Most small settlements in both Fennoscandia and Russia continue to decline markedly in size while a substantial number of larger settlements have also suffered the same fate. Changes in the prevailing demographic parameters especially in terms of declining birth rates have been a major factor here though out-migration from smaller to larger settlements and continued migration out of the region as a whole have also been important.

The places which have experienced major growth in Fennoscandia and NW Russia are those where educational opportunities are available. Similar patterns are shown in the North Atlantic region where Nuuk, Sisimiut and Thorshavn have been the big receivers, while most of the smaller settlements have experienced a decline.

In the Western part of the Arctic a few of the smaller settlements and most of the larger ones have experienced population growth while some smaller settlements have experienced either moderate growth or decline.

There are differences in the reasons for growth. In Alaska in-migration is an important factor, just as the still relatively high birth rates contribute to growth even in the smaller settlements despite the fact that out-migration plays an important role here also. A similar situation is experienced in the Canadian territories, although with a different weight on the various parameters involved; Yukon and NWT with in-migration contributing while high birth rates remain important for Nunavut, Nunavik and Labrador.

Just as public employment has been something of an Arctic trademark public housing has also made an important contribution to improving housing conditions in the Arctic. Rented dwellings – apartments, terraced or semi-detached houses as well as individual houses – often in connection with employment and with favourable rental conditions as part of the employment contract also remain important in many regions. The current situation is shown on the map, and illustrates a divide between the regions – Greenland, Nunavik, Nunavut, NWT, Chukotka, Taimyr and Nenets – where most individual dwellings are rented, and the other regions where there is a dominance of owner-occupied dwellings.

In the Faroe Islands almost all dwellings are privately owned. Only a few apartments are rented out and these are typically basement apartments rented by students or single persons. Nunavik, Nunavut and Greenland are among those regions where the majority of dwellings are owned by public organisations, for instance in Greenland by the Government or the municipalities, or in a few cases by large companies.

Looking back just 15 years the picture would have been very different. In Russia where the majority of dwellings today are privately owned, fifteen years ago most would have been either state owned or owned by cooperatives. And fewer dwellings in Greenland were also privately owned at that time. The processes of privatisation in Russia and Greenland have however been very different, in Russia the process occurred over a very short period of time, while in Greenland it has been much more evolutionary in nature. A similar process is only now taking place in the Western Arctic areas of Canada.