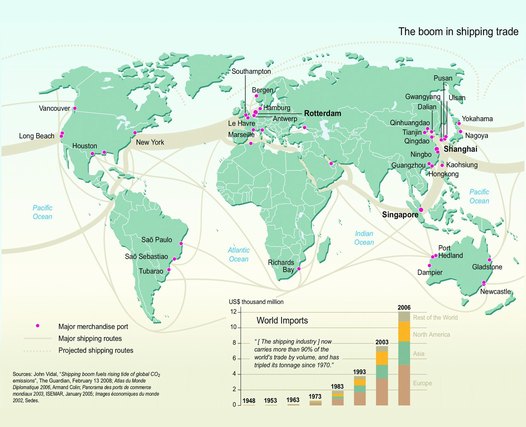

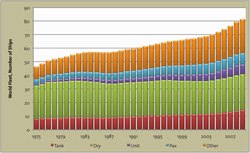

Over the last 25 years, the volume of maritime transportation has increased rapidly. The world trade fleet of vessels above 100gt increased by 75% to more than 81 400 vessels. Freight capacity increased by 129% to 1 306 million deadweight tons, while the current trend is towards even larger vessels. Due to investments made before the recession the fleet is expected to continue to increase by another 10% and freight capacity by 32% up to 2014.

The Nordic countries have a long maritime tradition and sea transport is important for numerous economic activities. For example, Norway has a history as a world leader in shipping, about 90% of Sweden's international trade volumes pass over the sea while Denmark has one of the largest operating trade fleets in Europe. Due to their geographic location, heavy process industries in the north of Sweden and Finland are also highly dependent on sea transport.

Even if the number of persons employed on board is limited, and indeed declining, sea transport remains important for employment. Using the broad definition contained in the EU Bluebook An Integrated Maritime Policy for the European Union, which includes directly related activities, e.g. ship brokers, harbours, offshore activities and shipyards, as well as sectors such as water-based natural resources, tourism and the public sector more generally, the number of employees is actually much larger.

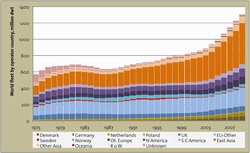

Shipping is one of the most 'international' business sectors in the world and competition is increasing. In line with the rest of Europe Norden's share of sea transportation is declining. Since 1975, East Asia has more than doubled its share of the global trade fleet to 33% of the vessels.

During the same period, the EU27 and Norway have, together, seen a reduction in their share from 27% to 18% of the global share of vessels. In spite of a generally positive economic development trend during the 2000s the Swedish share of the world trade feet fell from 1.3% to 0.6%, or 451 vessels, while the Norwegian figure fell from 2.1% to 1.9%, or 1 536 vessels, since 1975. Only Denmark has seen a small increase, from 0.7% to 0.8% of the world fleet, or 618 vessels.

During the same period, the EU27 and Norway have, together, seen a reduction in their share from 27% to 18% of the global share of vessels. In spite of a generally positive economic development trend during the 2000s the Swedish share of the world trade feet fell from 1.3% to 0.6%, or 451 vessels, while the Norwegian figure fell from 2.1% to 1.9%, or 1 536 vessels, since 1975. Only Denmark has seen a small increase, from 0.7% to 0.8% of the world fleet, or 618 vessels.

In terms of freight capacity, the greatest expansion, since 1975, has been among countries in South and Central America. Today, one third of the world's freight capacity is registered in these countries, compared to 21% in East Asia and 18.5% in Europe.

Still, in Europe as well as in South Asia, the number of vessels operated is higher than the number of vessels registered. Overall, 21 300 vessels are operated by shipping companies in the EU27 and Norway, compared with the 15 000 vessels actually registered in the area. These are mainly vessels operating in trans-ocean markets for tank, dry bulk and container transports. The largest European operators are the UK, Denmark and Germany, with 63.6, 57.4 and 44 million tons. In Norway, the operated volumes are 33.1 millions and in Sweden 9.4 million tons.

In 2009, the EU presented a Maritime Transport Strategy for 2009-2018, with a focus on shipping and related industries. According to the report, about 1.5 million persons are employed in the maritime transport sector (broadly defined) across Europe, about 70% of them onshore, for example in shipbuilding, design, research, distribution and logistics. The maritime sector is also a motor for economic growth, representing large shares of GDP (gross domestic product) and exports.

At the same time, it is argued that the sector faces several challenges including a volatile demand structure, increased globalisation, the effects of the financial crisis, the risks associated with protectionist behaviour, environmental demands, energy insecurity and the risk of losing competence in the maritime sector.

To increase competitiveness in the maritime sector, many larger maritime nations in the EU have developed maritime strategies and introduced different incentives to support the shipping industry. Denmark, for example, has developed the vision "Blue Denmark" while Norway has developed a maritime strategy for environmentally friendly growth, "Stø kurs". Both countries have introduced international registers, to reduce costs by employing onboard personnel from low cost countries. In an attempt to facilitate long term investments in vessels and compensate for high capital costs and a volatile market, several countries, including Denmark, Finland and Norway, have also introduced tonnage taxation.

To increase competitiveness in the maritime sector, many larger maritime nations in the EU have developed maritime strategies and introduced different incentives to support the shipping industry. Denmark, for example, has developed the vision "Blue Denmark" while Norway has developed a maritime strategy for environmentally friendly growth, "Stø kurs". Both countries have introduced international registers, to reduce costs by employing onboard personnel from low cost countries. In an attempt to facilitate long term investments in vessels and compensate for high capital costs and a volatile market, several countries, including Denmark, Finland and Norway, have also introduced tonnage taxation.

In Sweden interest in the maritime sector has increased during the recent recession as the economic situation of some shipping companies has become acute. Even if the question of tonnage taxation has been postponed until after the coming election in the autumn of 2010 several investigations have been initiated including a study concerning a possible international register.

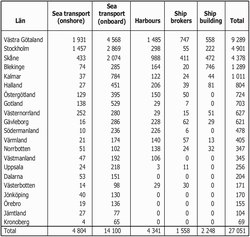

In April 2010 a background analysis of the Swedish maritime cluster was presented to the Swedish Government. According to the report the Swedish sea transport sector had a turnover around SEK 45 billion in 2008. Together with other directly related sectors, such as harbours, ship brokers and ship building, it accounted for around 27 000 jobs in Sweden. The main concentrations were found in the larger city regions, but some smaller regions such as Blekinge, Strömstad and Gotland also had high levels of regional specialisation in certain segments.

The level of education in the sea transportation sector is high and it has important cluster effects in terms of competence spill-over to other sectors. With a broader definition of the maritime sector, including suppliers, public sector and leisure boats, but excluding parts of the tourism and transportation sectors, more than 110 000 persons are affected. In spite of this, the shipping industry is relatively unknown to the general public and there is no national maritime strategy in Sweden.

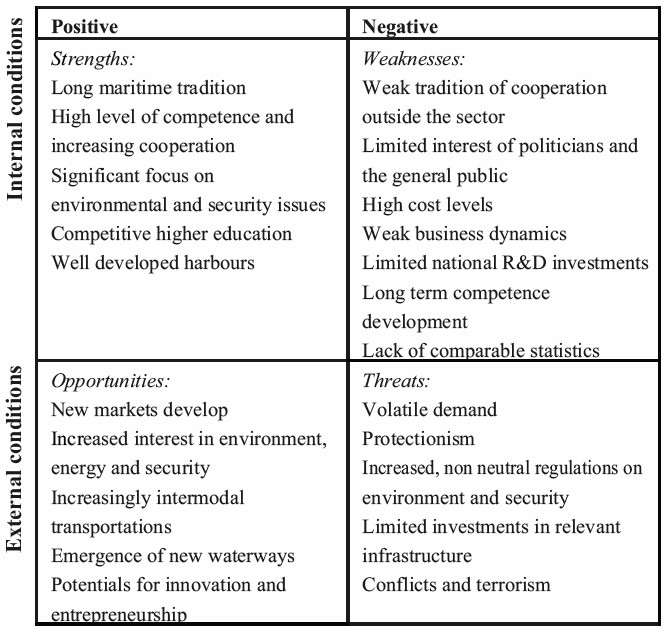

Based on a SWOT-analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats), the report indicates the potential for the future development of the maritime sector, but this requires regional or national initiatives to reduce the sector's weaknesses and the impact of current threats, for example the new sulphur directives in relation to the Baltic Sea.

One of the main recommendations of the report is to develop a Swedish maritime strategy using a cross sector approach involving both private and public actors. This could increase the Nordic influence on prioritised questions for the shipping industry, such as the environment, energy efficiency and security, within the EU. It could also provide the potential to develop an internationally competitive sea transport sector, by increasing entrepreneurship, stimulating innovation and facilitating the long term supply of competence in the field. Many of these initiatives could be taken at the Nordic level, to further increase the Nordic countries' leverage in the EU.

• Develop a Swedish maritime strategy

• Increase the knowledge level among policy makers

• Stimulate development through cooperation

• Look into the fee systems

• Create a stronger public structure in the maritime sector

• Develop the mission of the Swedish Ships´ Mortgage Bank

• Increase national R&D investments in the sector

• Reduce the effects of the new sulphur directives

• Secure future maritime competence

• Speed up relevant infrastructural investments

Table 3: Policy recommendations to the Swedish Government

Figure 1: The world trade fleet, per market segment (1000s of vessels) Källa: Tillväxtanalys and Lloyds Register Fairplay, 2010

Figure 2: The world trade fleet, per operating country in million dwt. Source: Tillväxtanalys and Lloyds Register Fairplay, 2010

Larger ships require new infrastructures

The M/V "OOCL Germany" (above) a Panamax class ship. It is 277 m long, 40 m wide and can carry 67 500 tons in a 14 m draught. Maximum speed is 26.1 knots. Photo provided by E.R. Schiffahrt

Container ships now transport the majority of the world's production of dry cargo and the container fleet is expanding faster than other parts of the world fleet, mainly due to the increasing size of vessels. The transoceanic container fleet can be divided into different categories according to loading capacity:

Panamax – the maximal size of vessels operating in the Panama Canal today. The current floodgates limit the size of ships to a maximal width of 32 metres, a length of 294 metres and a depth of 12 metres. This corresponds to a volume between 4 500 and 5 000 TEU (Twenty-Feet Equivalent Unit).

Post-Panamax – are the largest ships that may operate in the Panama Canal after the ongoing expansion of the floodgates has been completed in 2014. These ships may be up to 49 metres wide, have a total length of 366 metres and a depth of up to 15 metres, corresponding to a volume about 12 000 TEU.

Super Post-Panamax – are the largest Post-Panamax ships that can operate in the Suez Canal today. They may have a width up to 50 metres, a length of 400 metres and a depth of almost 15 metres, resulting in a total volume of 14 000 TEU.

Malaccamax – in the future, even larger ships, with a volume of up to 18 000 TEU may be expected. These ships are the largest ones than may operate in the Malacca Sound, but they are too large to operate in the Suez Canal before the planned expansion has been effectuated.

A continual increase in the size of vessels requires infrastructural investments, primarily, the expansion of canals and harbours. Today, there are few harbours in the world that have the capacity to handle the largest ships. In Sweden, for example, the only harbour with cranes large enough to service Post-Panamax ships is Gothenburg.