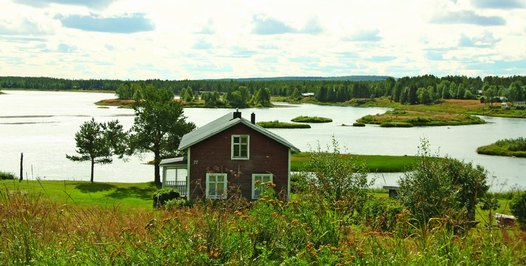

In Norden, rural development has not, traditionally, been viewed as a policy field in its own right. Photo Tornedalen, Sweden by Odd Iglebaek

With the EU accession of Denmark, and subsequently also some twenty years later of Finland and Sweden, greater attention has been given to the issue of rural development than was previously the case while recent years have also seen a move away from regional balance towards a greater focus on competitiveness and regional growth.

In contrast, since 1945, Norway has attempted to maintain established settlement patterns, thus distinguishing it from the other Nordic countries. Danish strategy has shifted from supporting national redistribution and welfare service provision towards a greater focus on grassroots developments. Swedish politics has become increasingly characterised by the move from a focus on regional equalisation policy to the creation of competitiveness based on the intrinsic strengths of each region. Environmental issues are also important in rural policies. In Finland rural development politics have attracted greater attention over the last twenty years. Finland remains characterised by a holistic view of rural areas and by the search for a coherent policy covering a number of administrative sectors.

Denmark1

The Danish welfare state developed after the Second World War supported decentralisation and aimed at distributing the wealth of the country evenly between places and people. This idea was further strengthened by national and municipal reforms in the 1970s and until recently signs of convergence between the different regions could be seen.

The so-called 'village movement' was the first policy initiative to draw attention to the need for a more explicit rural development policy in Denmark, a policy which went beyond regional and agricultural policies. Local associations mobilised to make the voice of the countryside heard during the 1980s and 1990s. In 1997 the first national rural development initiative was born and designed to support development initiatives at the local level. Recently the role of the village movement was enhanced when the local action groups (LAGs) were strengthened in the implementation of the EU rural development programme.

The state, the primary sector and civil society have all taken part in shaping the rural development work that today mainly consists of support programmes for local development projects combined with business and environmental support to the agricultural sector. In recent years the socioeconomic difference between regions has increased as state service supply decreases and competition between places increases imposing a whole new set of challenges for rural development policy.

Finland 2

The 1960s and 1970s saw a period of heavy urbanisation and structural change in Finland. This gave rise to the first measures directed at peripheral areas concerning issues beyond agriculture. In addition a more holistic approach highlighting the desirability of conceptualising entities as being composed of nature, people and different activities emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. These changes also gave rise to the Finnish village movement, today one of the cornerstones of the country's rural development policy.

At the beginning of the 1990s a national rural policy committee with representatives from a number of different administrative sectors was created. The rural policy system has since then expanded, and today consists of both a broad policy outlining the direction and a narrow policy containing different project support measures. This is designed to ensure cross-cutting territorial rural development at all levels.

The key focus here has long been on enabling rural areas, including remote areas, to keep pace with urban areas. In recent years however regional policy has, as elsewhere, focused increasingly on competitiveness.

Norway3

The Norwegian welfare state was developed after 1945 while the country recovered through economic growth based on the transfer of labour from the primary sector to industries in more urban settings.

The first actions to reverse the relative decline of rural areas came in 1961 when a public fund was established to prevent the loss of rural jobs and depopulation. The term rural was never, and is still not, used. The term districts has historically been used instead. Specific policies for agricultural, fisheries and businesses were developed with the aim of creating a balance between rural and urban areas.

In the 1960s and 1970s the development of infrastructure and industry as well as the decentralisation of higher education was high on the rural policy agenda. Since the 1980s competitiveness, deregulation and the development of regional urban centres has again, however, been the main focus. Compared with the other Nordic countries however Norway remains, to a much greater extent in their sectoral policies, focused on adapting to the situation in the different regions.4

The political debate in Norway, over the last fifty years, has been dominated by two camps; one promoting decentralised growth and local development initiatives, the other promoting policies focusing on the provision of infrastructure and growth centres. Current policies are a mix of the two but the focus is still to some extent placed on sustaining existing settlement patterns.

Sweden5

A strong welfare state policy dating back to the 1950s, a redistributive regional policy and a well developed local public sector have helped for many years to minimise urban-rural disparities in Sweden. Specific policies supporting the primary sector played a role in the early part of the second half of the 20th century but were phased out by the 1990s. Reappearing after EU membership was attained, these types of policies gained public acceptance when designed to support environmental solutions to various problems. While the focus was primarily on incomes for farmers this was not however the case.

In the 1970s the welfare state model started to weaken, partly in the wake of increased globalisation and the influence of neo-liberalism. One result was a gradual change in regional policies, from redistribution towards competitiveness and endogenous growth. The aim of achieving regional balance in economic development was thus largely superseded.

In the late 1980s policy started to attach more importance to local village associations and community initiatives. "Regional enlargement"; increasing labour markets, has also attracted more interest as a tool for sustaining rural areas. Today remoter rural areas are characterised by net out-migration.

The author would like to thank Nordic Working group on Rural Development Policy, Hanne Tanvig, Senior Researcher and Adviser, Forest & Landscape, University of Copenhagen and Professor Reidar Almås, Centre for Rural Research, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, for providing background information for the Danish and Norwegian analysis undertaken herein.

1) Based on information provided by Hanne Tanvig. 2) Petri Kahila, Deliverable D1.1 Country profile on rural characteristics, Finland, RuDI project. 3) Based on information provided by Reidar Almås. 4) Means and instruments for the implementation of the national policy. 5) Petri Kahila, Moa Hedström, Deliverable D1.1 Country profile on rural characteristics, Sweden, RuDI project, Jon Moxnes Steineke, Petri Kahila, D2.2

National report on RD policy design Sweden, RuDI project.