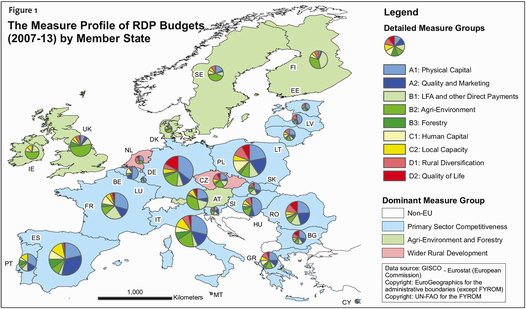

Figure 1: Profiles of Expenditure 2007-13 Rural Development Programmes

Source: RuDI Project

The disadvantage of this has been the failure of Axis 3 (which addresses broader rural issues) to flourish, and a tendency for national/regional programmes, often administered by agriculture ministries/departments, or there successors, to "retrench" by focusing disproportionately upon Axis 1 (farm structures and competitiveness) and Axis 2 (agri-environment). In addition many observers have expressed concern that the mainstreaming of the LEADER Community Initiative as Axis 4 has so fundamentally changed its character that it is no longer an innovative driving force for change in rural communities.

The current programming period runs until 2013. Behind the scenes discussions about the shape of rural development policy from 2014 have been taking place in the Commission, and between the Member States for at least a year. Various publications, notably the Barca Report, and reflections by both Commissioners Hübner and Samecki1 and conferences such as DG Agriculture's The CAP Post 20132, have been used as vehicles to developed arguments and test the reactions of key stakeholders. The coming months represent a window of opportunity for change. Decisions will be made which will have substantial implications for the future of rural Europe in the medium term.

Recent programming periods have produced rather conservative "incremental" changes; new measures have successively been added; the existing "menu" has been restructured. There is however a risk that this form of policy development gradually becomes out of touch with the reality of the rural areas and issues that it is intended to address. The danger is heightened by the new challenges posed by the post-recession economic environment, and climate change.

It is hardly surprising that the current debate has produced demands for a major rethink on how best to address the broader needs of rural areas in Europe, including calls for Axes 3 and 4 to be brought back into the Cohesion policy fold, by transferring responsibility for them to DG Regio.

Both directorates are expected to make significant announcements regarding plans for the new programming period during November of this year. No doubt the proposals that emerge will be orientated towards the overarching aims of EU2020 ("smart, sustainable and inclusive growth"), and DG Regio's at least will reflect the philosophy of supporting potential rather than compensating disadvantage.

Within this context then of a need for a radical rethink of EU rural policy Nordregio has participated in two research projects which in their different ways have each contributed substantially to the necessary "evidence base" for the debate. The first is RuDI (Assessing the impact of Rural Development Policies), and is part of the 7th Framework Research Programme. The second is the ESPON project EDORA (European Development Opportunities for Rural Areas).

The reports and working papers of these projects are a rich source of relevant information, and it is only possible to provide some key points here as examples of the direction of travel: There is a substantial "gap" between the concepts and theories presented in the academic literature and the policy rationale presented in the documents supporting the 2007-13 programme (RuDI report on WP1).

During the 2007-13 programme the expenditure plans of the majority of Member States are dominated by either agri-environment or agricultural structures and competitiveness – the wider rural economy, social and human capital, are very much "poor relations", and on the evidence so far, are unlikely to reach even these modest spending targets (RuDI report on WP4-5 – Figure 1).

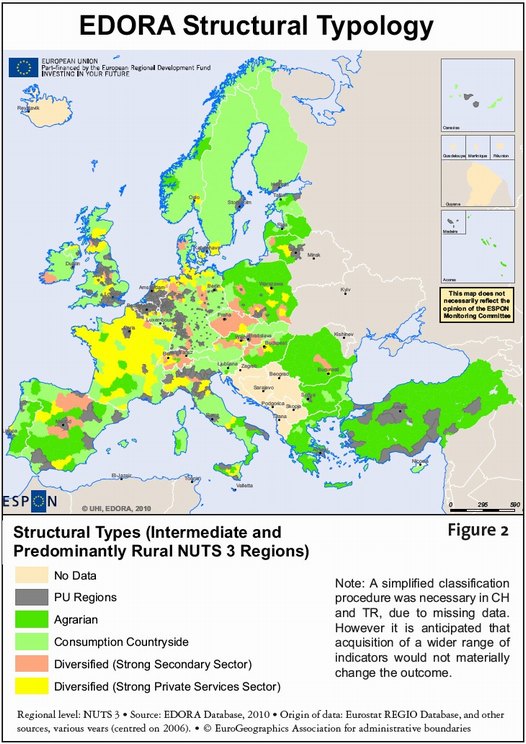

Substantial differences exist between rural areas in different parts of the Union (Figure 2). The EDORA Structural Typology of "non-urban" NUTS 3 regions shows that "Agrarian" (dark green) regions are largely confined to the New Member States and the South. In the less accessible regions of the Nordic Member States, and in some other parts of Western Europe, the rural economy is more likely to be orientated towards delivering "rural amenities" (light green) including leisure, recreation, tourism, and the conservation of countryside public goods. In more accessible areas the rural economy tends to be much more diverse (yellow). In the New Member States of Central Europe secondary (manufacturing) activities (pink) generally play a more substantial role than traditional land-based industries, whilst further west the "New Rural Economy" is characterised by service activities.

The above typology represents a high degree of simplification and generalisation. Although the "menu approach" of the current Rural Development Regulation (2005/1688) is intended to accommodate the rich and increasing diversity of rural Europe, the reality is that, with one or two exceptions, national and regional rural development programmes are still strongly sectoral, rather than territorial. On the whole they address the needs of a minority economic sector/social group, rather than those of the majority of the "non-urban" enterprises and population, and hence they fail to reflect the differences in the local rural economy.

A common phrase in the recent discussion, especially from the DG Regio side, has been "rural-urban relationships". These are seen as a potential driver of territorial rural development. On closer examination (in the context of EDORA) the terminology turns out to be frustratingly ambiguous and to present some weaknesses in terms of its "functional/city region" rationale. Whilst there is some development potential to be derived from the "relocalisation" of regional and high quality food industries, and perhaps other "rural amenity" activities, most rural economies will benefit more from a balance between connections with both nearby urban areas and more distant sources of information, innovation and demand (whether urban or rural). Rural-rural and rural-global linkages are likely to be as important as rural-urban.

Globalisation and increasing "connexity", even in remote rural regions means that development opportunities are increasingly ubiquitous. The determinants of the development path, and thus of the prosperity, or otherwise, of any individual region are likely to be place-specific assets and capacities, broadly defined, and including "soft" factors such as human and social capital, quality of governance, "institutional thickness" and so on.

If it is to address cohesion objectives, such as balanced regional development through enabling rural areas to exploit their potential, EU Rural Policy will need to steer carefully between the risk of a narrow agrarian focus on the one hand, and becoming swallowed up by regional/cohesion policy which sees rural areas as having a supporting role in an urban dominated regional growth process, on the other. It is rather disheartening that the current debate tends to overlook the fact that rural regions can, and often do, exhibit an endogenous dynamic in activities well beyond the rural amenities "comfort zone".

Figure 2: The EDORA Structural Typology

Source: EDORA Project Working Paper 24

1All these documents may be found at http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/policy/future/index_en.htm

2 http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/cap-post-2013/conference/index_en.htm