The European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP) identifies a European core area, delimited by the London, Paris, Milan, Stuttgart and Hamburg metropolitan areas and designated as the 'Pentagon'. Within this zone, one can observe a concentration of people, wealth production and command functions. This concentration is judged detrimental by the ESDP. The ESDP moreover claims that the main driving force behind the Pentagon's development is its status as 'global economic integration area'. In consequence, the solution to improving the territorial balance in Europe would be to develop alternative zones of 'global economic integration' through an increased level of integration between existing metropolitan areas. The ESDP in other words favours the idea of multiple 'Pentagons' across Europe.

Where does this leave the Nordic countries? None of the Nordic cities can claim to be 'Global cities'. There is also very little hope that integration between the existing urban regions would ever allow them to achieve a higher degree of global significance. There is, in other words, no potential for creating Zones of global economic integration able to counterbalance the Pentagon in Norden. But does this imply that the Nordic countries are bound to be increasingly subjected to centralising European trends?

Economic trends over the last decades tell a different story. The lack of globally significant nodes has not prevented the Nordic countries from experiencing an overall level of economic development that is either equivalent or superior to that of the European core areas of Germany, France or the Benelux countries. Given this relative Nordic successs, how then should they now relate to European spatial planning's focus on globally significant urban nodes?

What is globalisation about?

The globalisation debate can be traced back to the mid-1970s when some academics observed that multinational companies had begun to transcend the nation state. From the mid-1980s onwards, there was an increasing awareness that a new hierarchy of global cities was emerging.

Demographic size is not the core element of this hierarchy. A city's importance depends rather on the number of transnational company headquarters, high-level financial services and other advanced business-to-business services it hosts. The presence of such 'global activities' implies a concentration of economic command functions.

In parallel, the role of the nation state is shifting, from impulse provider and decision maker to enabler and regulator. The awareness that cities can transcend states becomes a central element in geographical debates over globalisation.

As such, one can easily demonstrate that these so-called 'global activities' are largely overrepresented within the European core or 'Pentagon'. But is this sufficient to earn global city status?

It has been demonstrated by global city researchers that the types of activities that are characteristic of global cities require large labour markets because of the wide scope of specialised competencies that need to be pooled. This however implies the need for a large number of persons living within commuting distance of each other, within the same city or metropolitan region. Inter-urban entities such as the Pentagon are difficult to relate to this view of the global city.

'Global integration zones':An answer to territorial challenges?

What does the ESDP then imply when it characterises the 'Pentagon' as a "zone of global economic integration"? One does indeed find a higher concentration of people there than in the rest of Europe, whose share in the continental production of wealth is more than proportional.

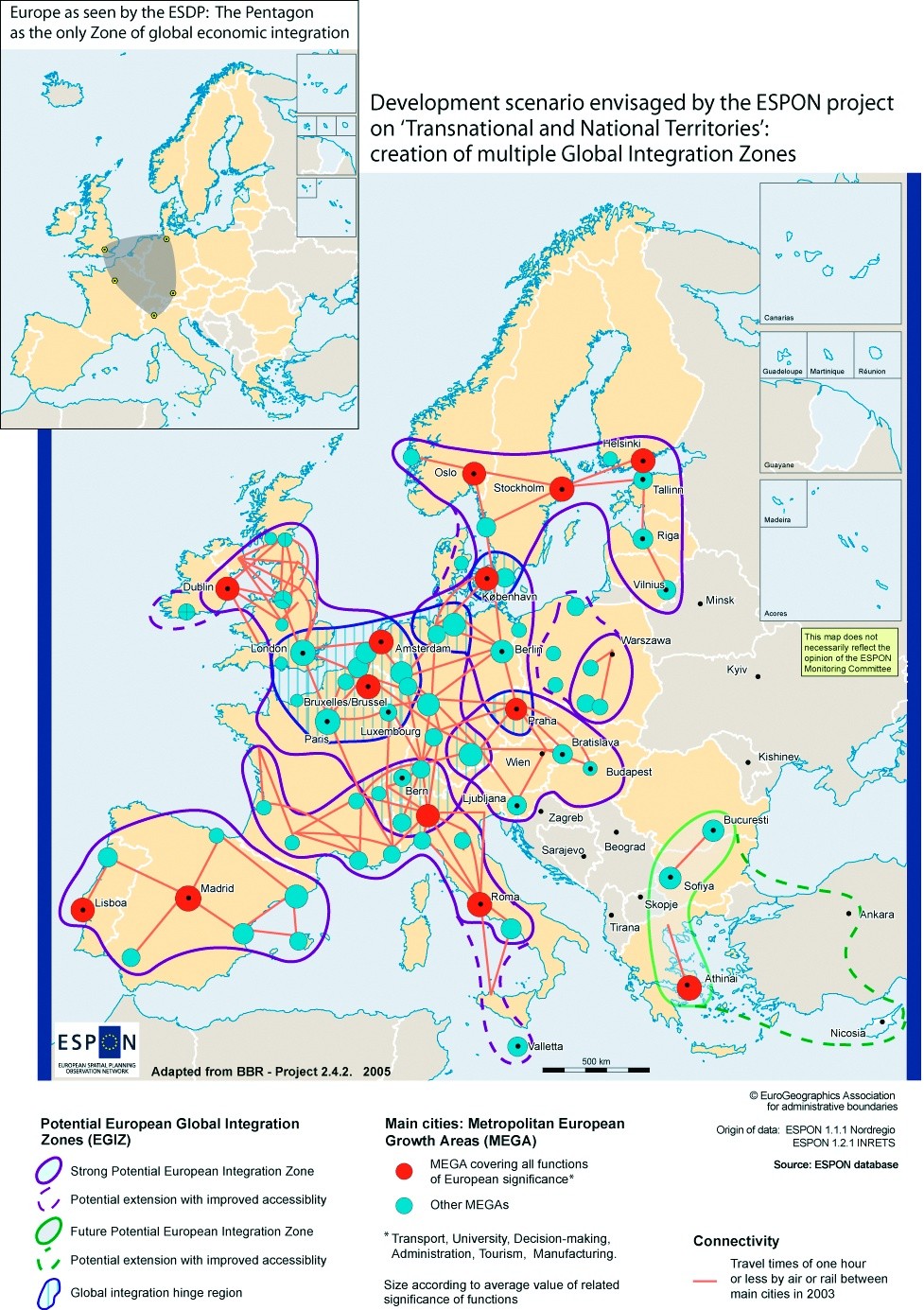

This production however develops within competing cities; the rest of the European territory does not relate to the 'Pentagon' as such, but to a given city or metropolitan region within the Pentagon. The 'Pentagon' is a geographical concentration of globally significant cities. But it is strikingly heterogeneous, and contains a number of regions with structural challenges and a weak connection to global economic circuits. ESPON however tends to consider the 'Pentagon' as a "recipe for growth". The development scenario map of Figure 1 assumes that global integration can be further developed if neighbouring metropolitan regions integrate and cooperate. It therefore builds zones with major, functionally well-endowed, metropolitan regions within one hour from each other by rail or air.

These zonings are selected so that access to the large cities is better within each zone than between the zones. Actors at all scales are presumed to turn to the metropolitan regions within their zones for global connections, rather than to other cities. More generally, global integration is seen as contingent on spatial proximity to metropolitan regions.

Figure 1: A Europe of Global integration zones

According to this approach, global integration occurs through major metropolitan regions. It can be further developed if neighbouring metropolitan regions integrate and cooperate. The zonings also suggest that areas situated around and between the concerned metropolitan regions can benefit more from global integration than other parts of Europe. Nordic regions north of the capitals are therefore considered as having a lower potential for global integration.

Northern Norden: An alternative model?

This produces a scenario in which Mid- and North-Norden are excluded from global integration, in spite of these regions' high proportion of industries operating on the global market. These traditionally export-oriented economies have forced Nordic regions to integrate into global economic circuits, and to develop a deeply rooted culture of adaptation to external change.

Their economic performance is linked to a process of global integration in which distance to the European 'Pentagon' has not been a significant obstacle. They demonstrate the need to differentiate between "global command functions", of which they have few, and "globally integrated activities", with which they are richly endowed.

This in turn should encourage a revised approach to European territorial balance. If "global integration" is more important than "global command functions" in achieving regional economic growth, the objective should not be to "counter-balance the Pentagon", but to promote better integration in global economic circuits in all parts of Europe.

This opens up a whole new set of possibilities, as the current urban structure of Europe is seen as less of a constraint on balanced European territorial development. It however also implies that other challenges need to be analysed and dealt with. Two main types of issues can be identified. First, global integration can put small labour markets in a vulnerable position. This higher degree of risk, and the ensuing periodical crises that will occur in some communities, require adequate political responses.

Secondly, the transport infrastructure needed for global integration is not necessarily the same as for European integration. A critical analysis of the European infrastructure priorities could therefore be envisaged, with a focus on peripheral industries' needs in view of improved global integration.

Changing the European understanding of global economic integration is in other words an important issue. Indeed, as counterbalancing the Pentagon is not an option in most European peripheries, these areas will be excluded from any policy pursuing this objective. As shown, this thinking however derives from an unfortunate conflation of 'global integration' and the 'presence of global command functions'.

The Nordic countries are in a particularly favourable position to advocate a focus on global integration in all European regions, irrespective of their size and situation. Their relative economic success, in spite of their peripheral location and small populations, shows that the harmonious territorial development of Europe does not presuppose the presence of counterbalancing 'urban zones'.

Territorial balance in financial service provision

The Nordic example shows that growth can be achieved without a massive endowment of high-level services and transnational company headquarters. Nonetheless, all economic actors, in some way or another, need to relate to these factors of economic power. The ease with which they can access risk capital, bank loans or insurance services is of importance for regional growth. A policy for European territorial development therefore needs to relate to the geography of global economic functions.

The question then is whether European spatial planning has the right tools with which to approach these issues. Both in the ESDP and in ESPON, the predominant approach has been developed in terms of regional or urban endowment with global functions. One can however ask whether global economic activity is relevant only for the city or region that hosts it, or rather to all actors that have access to it and can draw advantages from it.

Typically, an industrialist or entrepreneur in a medium-sized city in northern Sweden, with a good command of the English language and access to an airport with frequent connections to Frankfurt, London and Paris via Stockholm, can benefit from the global service offered in these cities relatively easily. A colleague in the north-western outskirts of the greater Paris region ('Bassin Parisien') will be just a few hours drive from a 'Global city', but may find it considerably more difficult to access the same range of global services.

Irrespective of this, European spatial planning is likely to characterise the geographic context of the former economic actor as "extreme periphery" while the latter would belong to a "global city's wider functional region".

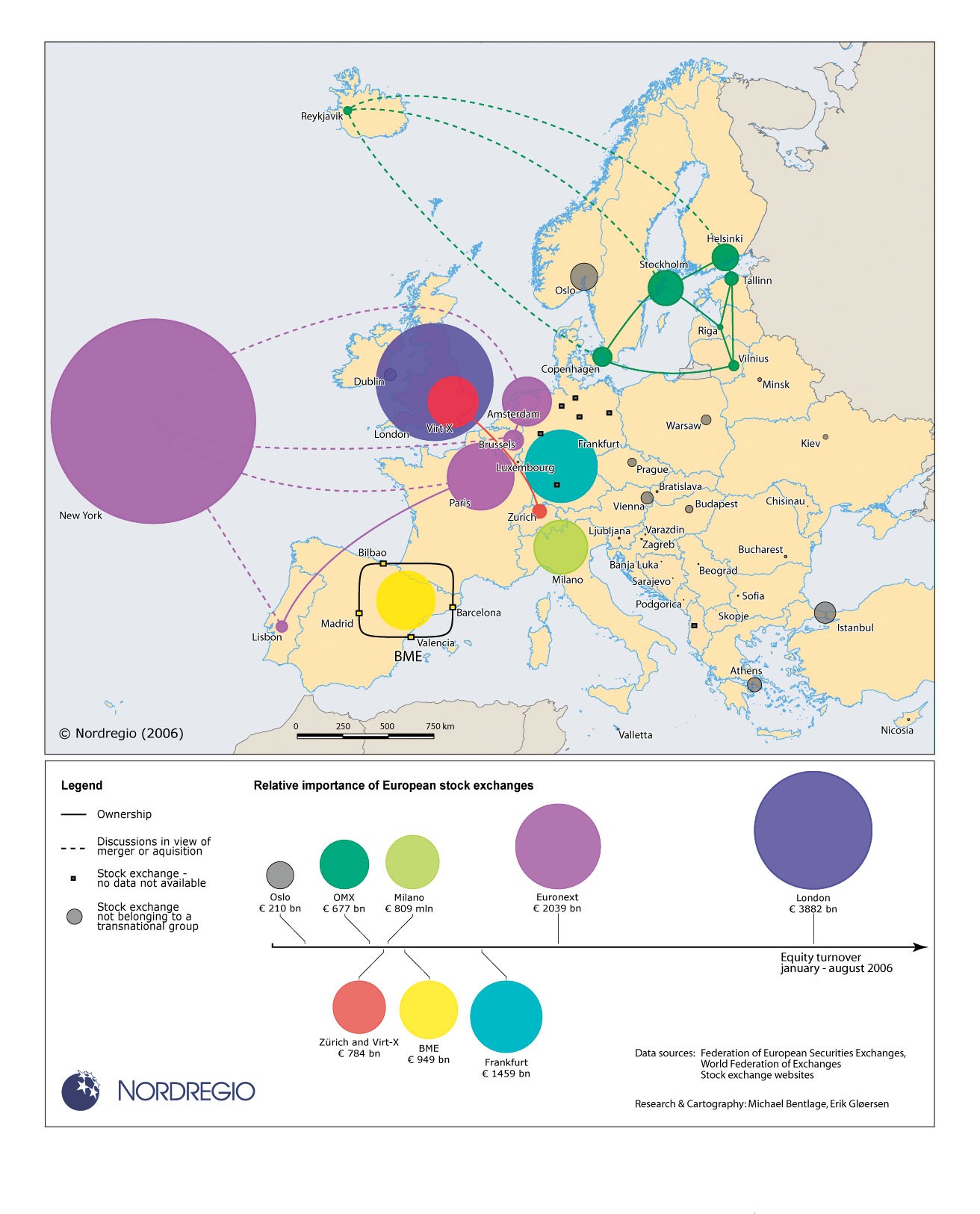

The second problem with a focus on regional and urban 'endowment' is that the functioning of high-level services is increasingly network-based. Stock exchanges, a typical high-level financial service provider, currently reinforce this network aspect through a series of mergers and acquisitions. Admittedly, geographic proximity plays a role in some cases. The integration of the main Nordic and Baltic stock exchanges (except Oslo) in the OMX group, and that of Spanish stock exchanges in BME illustrate the emergence of regional entities.

Other networks however develop independently of distance. The advanced discussion in view of a merger between the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and Euronext would for example create a trans-Atlantic entity transcending not only the nation states concerned, but Europe as such.

Another proposal suggests reinforced cooperation between Euronext, Milan and Frankfurt, and would constitute a more "Pentagon-like" type of entity. The discussions between the stakeholders however demonstrate that none of these processes are essentially linked to spatial proximity. Given these networking trends, the development potentials of a given region are related to the capacity of its economic actors to integrate with their counterparts, rather than with geographic proximity.

As shown by Figure 2, the geography of stock exchanges is characterised by extreme core-periphery contrasts. The contrast is especially striking between Eastern and Western Europe.

The total turnover of stock exchanges in all new member states, plus Bulgaria and Romania, amounts to less than 4% of the value of the London stock exchange. Oslo and Helsinki each have higher turnover values than all new EU Member States. In this context, networks in a given part of Europe, such as OMX in Norden and the Baltic countries, and BME in Spain, can at best compensate for the increasing integration between the most central and largest stock exchanges. Overall, current trends do not, it would appear, contribute to an improved territorial balance in Europe.

The zoning scenario of global integration defined by the ESDP and applied in ESPON is therefore increasingly inappropriate. The regional entities that are identified, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, will not counterbalance the Pentagon in a meaningful way. Furthermore, the transnational integration of global command functions is not based on spatial proximity, but on networks and shared strategic interests.

The core issue is therefore access to global economic functions, which depends on factors such as network connectivity, the reduction of linguistic and regulatory barriers and entrepreneurial cultures. Counting significant global functions in cities and defining 'zones' will not help build a more globally integrated Europe.

European spatial planning needs to integrate a more elaborate understanding of globalisation. Acknowledging that regions can still successfully integrate into global economic circuits without either a large population or by hosting global economic service activities and command functions would be a significant first step in this direction.

It is particularly important for Norden to promote a change of perspective. The prevailing view on global integration sets its capitals and southern regions off the rest of the national territory. Developing the individual profiles and roles of all cities and regions implies taking onboard their characteristics, rather than negating them artificially through 'zones'.

By Erik Gløersen, previous Nordregio