Click on picture - to see the panorama of Copenhagen - as seen from Vor Frelsers Kirke in Christianshavn. To the far left SAS Scandinavian Hotel, Amager, 26 storeys high. To the right with the white roof, the new Opera house. Photo: Rasmus Ole Rasmussen

On the edge of the city centre we can see the Hotel Europa (1955), the Royal Hotel and the SAS Hotel (1960). Between the towers Copenhagen is characterised by a relatively unbroken flat profile. The city did not participate in the international trend in the construction of tall buildings which began in the 1920s. The general principle, adhered to since then by city planners, is that the size of new buildings should relate to their surroundings.

During the last economic boom tall building projects did however finally start to appear in the centre of Copenhagen. In particular controversy erupted because of six tall buildings planned for Krøyers Plads in Christianshavn. They were only 55m tall and were sketched by the Dutch architect Eric van Eferaat. The project was however terminated at the planning stage. If nothing else, what came out of this was that from this point on Copenhageners were seen to be ready to seriously discuss any suggestion for a new tall building project which emerged.

Tivoli and Scala

In November 2006, Tivoli initiated an architecture contest which was won by Foster and Partners. This caused heated debate, not least because the 102m tall tower would challenge the town hall tower and because the castle in Tivoli would have to be demolished.

In 2007 an architecture contest was issued for a tall building across from Tivoli, where a cinema, Scala, is located. Architects from the firm BIG won the contest with a 130m tall building swung with an exterior stairway sequence from Axeltorv halfway up the building.

In spring 2007, the Lord Mayor launched a debate on tall buildings in Copenhagen. In the discussion paper Tall buildings in Copenhagen – strategy for the city's profile, tall buildings are attributed many qualities: They create identity when big city regions are competing, they can serve as driving forces for urban development, they have great symbolic value, they create proximity, they express urban life, they create identity and are sustainable. These are just a few of the 'magical' qualities often assigned to tall buildings, which in reality however, remain rather dubious.

Desire for Landmarks

It seems then that, in Copenhagen at least, ambition in respect of tall buildings is driven by the desire to build landmarks and symbols. After all, Malmö has its 'Turning Torso'. Moreover, in the suggestion for the municipal plan 2009 a common argument in support of tall buildings is that they strengthen the image of Copenhagen as a dynamic metropolis and e.g. attract more international companies and tourists. Buildings can be used for a lot of things, but with this kind of objective such narratives rarely have a happy ending.

Copenhagen's tall buildings thus find themselves in the middle of an ongoing struggle between two rather different sets of interests. On the one side are, typically, the city's residents who want a relatively low city and who in any case want to maintain the medieval town ambiance represented by the verdigris towers. They believe that this is Copenhagen's distinctive feature and the city's strongest brand. A survey from 2007 showed that 7 out of 10 Copenhageners were against tall buildings within the embankments.

On the other side of the debate are the representatives of local government, developers and branding consultants. They believe that the city needs to show itself as a dominant modern metropolis and must therefore have tall buildings that visibly tower over the old city and serve as architectural showpieces.

Low city-centre zone

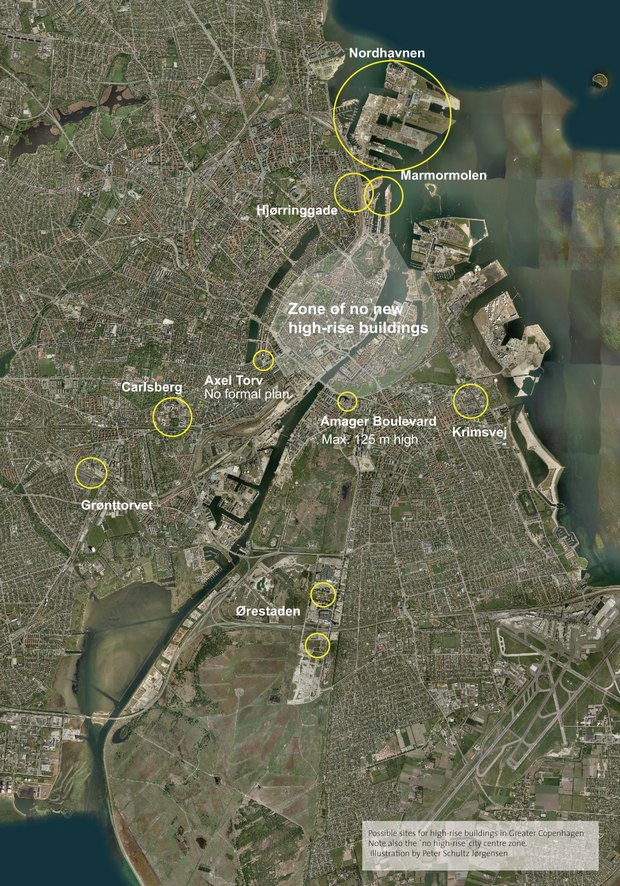

This spring, the municipality of Copenhagen presented a new suggestion for the municipal plan 2009. It was at this time that the debate on tall buildings was to be actualised in the binding plan. It is clear however that the recent public debate on tall buildings in Copenhagen has taken its toll. The main proposal however only forwards a single negative plan by marking out a zone where no tall buildings can be built. This zone comprises Christianshavn and the inner city to the lakes.

In addition no overview was made of where tall buildings could be built beyond this zone. Instead tall buildings are laid out half hidden in loose area plans and framework conditions. The tall buildings which for the moment have been laid out are placed in large new extension areas. Along the way however, more tall buildings will ultimately appear.

Ørestaden and Carlsberg

As an expansion area Ørestaden has come quite far. Here, south of Fields, which is the largest shopping centre in Scandinavia, tall buildings as high as 85m are being built. The Copenhagen Towers project, with hotel and office space, has to be completed before the COP15 meeting in December. The so-called 3rd generation office structures have been designed by the architects Foster and Partners in cooperation with Dissling and Weitling. Between Fields and the Bella Center tall buildings of 40-70m can be built. Ørestaden as well as the waterfronts of Marmormolen and Nordhavnen is owned by the municipality of Copenhagen and the state.

The area of Carlsberg used to be the site of a large brewery complex. Now labelled 'our new city' in the coming years it will be extensively transformed. The development of Carlsberg is managed by Carlsberg Properties. New buildings will be built between the large, attractive, production buildings.

In total, Carlsberg contains 600 000 m2 of new floor space. Nine tall buildings can be placed here. The tallest may be up to 120m and the others between 50 and 100m. They will appear as scattered and pronounced towers in an area which will otherwise have the same character as the surrounding parts of the city.

BIG's architects 130 metre high Scala-project in the centre of Copenhagen (above) will probably not be build. At the rear the gates of Tivoli.

Highest building in Denmark?

Marmormolen and Langelinie will be connected by an elevated walkway, designed by the architect Steven Holl, running between two tall buildings. They are quite distinct and it is hoped they will serve as a landmark for the new harbour development at Marmormolen, Kalkbrænderihaven and Nordhavn. This is the newest and largest urban development area where tall buildings may be constructed. The high-rise building at Marmormolen, at 148m, will be the tallest in Denmark.

A final urban development area which must be mentioned here is in Valby. Tall buildings can be built north of Torveporten and in the area of the old vegetable market which will be transformed into a dense new urban area.

Plans also exist to build nine slim, tall buildings of up to 21 storeys in the old industrial area at Krimsvej, which is located across the new Amager Strandpark. The tall buildings at Krimsvej appear to be a central ingredient in the transformation of the industrial area as was the case with Carlsberg. The outline for their suggested function is however somewhat strange.

The local plan, which was up for discussion until 30 September 2008, noted that: For the tall buildings it is important that they have slimness, limberness and an architectural quality which lives up to their function as the city's points of orientation along the coast.

Who wants to live the 'high' life?

The municipality asks itself who wants to live in tall buildings: Tall buildings used for residential purposes can offer attractive living spaces with a panoramic view for people who would like to live in a place with a strong urban identity. Surveys point to the fact that such residences are especially desired by people with a modern, urban lifestyle who give high priority to work life, urban life and proximity to cultural opportunities. Meanwhile, there is reason to believe that more people will be interested in living in such tall buildings in the future as lifestyles and consumption patterns change.

This may be the case, but the municipality itself however refers to an interview survey from Rotterdam which shows that only 1-2 percent of the population would like to live in a tall building.

The municipality's strategy for tall buildings thus remains problematic. It is as if they had not yet realised why tall buildings were necessary or what it is they actually contribute. The proximity which is spoken of can more easily be achieved by means of other settlement forms.

The role of the Metro

Copenhagen has recently built a number of new metro stations with even more on their way. This represents a radical change in the city's modus operandi. Without metro stations Copenhagen would have few centres where the construction of a concentration of tall buildings successfully exploited the increase in traffic capacity. Thus the metro stations provide the city with significant development opportunities giving rise to more fundamental discussions over the city's structural development and character.

There is not, as is sometimes suggested, an automatic affinity between popular and low construction. The advanced popular perception can definitely be expressed in tall buildings as a delicate way of building, if the problems that are connected to it, such as price, climate condition and the urban space at street level, are resolved.

The ecological issue

By mixing functions in the building and by looking at the tall building as a completely new ecological type of construct it becomes, it is argued, an interesting type of building that seems well suited to Copenhagen. But we also see a lot of tall building projects which represent rather more the suggestion of a 'vision for the future of urban life' – created by the methods and ideals of the past – only more imaginatively than before. BIG's Scala project is an example of this. The 'mountain' on Islands Brygge however does seem to suggest the future.

There is nothing mysterious about tall buildings. New York has a lot of them, and there they have no debate. In Hong Kong there are more skyscrapers than in New York. Here the agenda is clear – forwards and upwards – but also here there is not much to discuss. In Copenhagen there are very few no tall buildings but there is a lot of debate. There is also a need for this. Why, how and where shall we build good tall buildings?

By Peter Schultz Jørgensen architect and urban planner, currently works as a development consultant in the Culture Department in the municipality of Roskilde. In his spare time he has written extensively, in the Danish media, on Danish urbanism.