Shaped by its particular topography at the meeting point of Lake Mälaren and the inner waters of the Baltic Sea, the City of Stockholm is situated within a unique natural landscape - characterized by islands and water - and thus by dramatic elevation level changes throughout the city.

The urban silhouette is particularly distinctive with a smooth horizon of buildings conforming to the natural contours of the landscape. Areas of higher altitude and abrupt elevation changes are accentuated by taller and more elaborate buildings though churches and other public buildings still dominate the skyline. In previous centuries, these features have been highlighted on the skyline and refined through deliberate planning and the rational use of these natural conditions. It seems unlikely however that such an approach will continue.

A thirty year hiatus

In Stockholm's inner city only a few older high-rise buildings, built between 1924 and 1964, are currently identifiable. For example, Europe's first skyscrapers, the Kungstornen, are two seventeen storey (60m) buildings constructed in 1920. A considerably taller intervention into Stockholm's urban landscape, the Hötorgskrapor is five identical high-rise buildings, each nineteen stories high (72m), and the twenty-five storey Skatteskraparan in Södermalm. Each of these projects was constructed during the 1950s.

Around the same time, a series of other high-rises were built on the outskirts of the inner-city, including the Wenner Gren Center (82m), the Folksam building in Södermalm, the Dagens Nyheter building (84m) in Fredhäll, built in 1964, and somewhat later, Foahuset. Thereafter there was something of a hiatus in high-rise building for a period of some thirty years until the Söder Torn was completed 1997.

The modern suburban districts at the time were characterized by somewhat dense, horizontally-orientated apartment buildings in green surroundings. Their centres usually received a tall building as a landmark, generally however not exceeding ten storeys (30m). The most well known example is Vällingby, but others include Bagarmossen, Björkhagen, Fruängen, Gubbängen, Hagsätra, Kärrtorp, Västertorp, Alvik and Blackeberg. In the same way as in central Stockholm the more elevated parts of the landscape were often further accentuated with the tallest buildings.

More recent developments however identify a trend towards still taller buildings also in the outer districts of the city. The landmark Kista Tower (see p 20) constructed in 2002 stands 156 metres high and is currently being followed by a neighbouring tower, as well as a high-rise building at the Älvsjö Conference Centre in southern Stockholm.

For many years, the planning principle was to restrict the further development of high-rise buildings in central Stockholm. However, the economic boom that began in 2000, made it easier to finance luxury residential and commercial high-rise developments in desirable locations across all parts of the city.

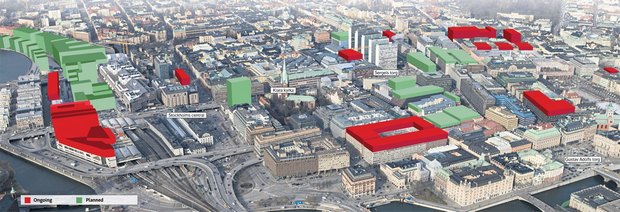

The future of Stockholm city – ongoing and planned. At present the most intensive densification is along the railway-lines from the north towards Central station. On the western side of the railway-lines four storys (red block to the left) have already been added to the previous nine storys and the 150m long Kungsbrohuset. The green block between Stockholms central and Klara kyrka reflects the plan to expand the Scandic Hotel to 100 metres. If built, it will be the first new skyscraper in the city since 1966. Photo and information provided by Stockholms Stadsbyggnadskontor. Graphical montage by Anna-Lena Lindqvist, Dagens Nyheter.

Building higher than 100 metres in the city?

Currently then we can see that there are several high-rise projects in the planning phase close to the inner-city – those in Alvikstrand, North West Kungsholmen, Norrtull and the harbour area are all examples of this. These buildings are expected to be significantly taller than previous high-rise constructions in Stockholm.

Current city plans include the construction of a high-rise tower exceeding 100 metres next to Stockholm's Central Station and another proximate to the City Terminal. Both buildings will be higher than the 'Tre Kronor' pinnacle at City Hall and the Klara Church crown, and will clearly disrupt the overall experience of these monuments as the defining points of Stockholm's skyline. Another is planned in the middle of Kungsholmen. Whether or not these developments will come to fruition however remains to be seen.

The development proximate to the Central Station, called 'Western City', will entail a significantly higher building envelope than the surrounding community. The project's first phase includes a 16-storey hotel as part of the new waterfront conference facility and is already under construction despite vociferous objections prior to development. This however highlights an all too common trend of political manoeuvring within Stockholm's planning process as it is currently laid out with the city first binding itself to development contracts and once they are in place only then attempting to implement a 'democratic' planning process.

For and against

Organizations that have voiced their opposition to high-rise buildings include the Stockholm Beauty Council, the Stockholm City Museum, and the S:t Erik Association.

From a political perspective, the spectrum of support for high-rise development in Stockholm is extremely varied. At one end, the Conservatives and the Center Party are favourable to the notion of high-rise buildings in the inner city, while the Liberal Party and Green Party are strongly opposed. Between these poles are the Social Democrats and the Christian Democrats. Similarly, The City of Stockholm's Planning Department has publicly expressed caution regarding high-rise development and remarked that further feasibility and public acceptance studies are required.

Lack of plans for the skyline

With the construction of the new Western City hotel we find ourselves at the limit regarding damage to the public interest. The municipal plans lack a clear understanding in respect of how the city intends to care for Stockholm's skyline, commented Stockholm County's Land Secretary Carl-Gustaf Hagander in an interview.

He continued: - As for the commercial and residential high-rises in the peripheral zone that are now under discussion, it is difficult to assess the impact they will have on the suburban built environment. However, examples of isolated buildings penetrating the skyline, such as the Dagens Nyheter building in Kungsholmen, behind the Old City seen from the sea, urge caution about the potential impact.

Costly and not environmental

Given the well-reasoned arguments of regional planners who favour an emphasis on multiple cores of medium density development, one must wonder why some politicians are so persistent in their ambition to build a dense, vertically-oriented urban core. What is more, representatives of the construction industry also warn of the excessive costs associated with high-rise buildings because of the complicated foundations, heightened fire safety requirements, complex structural engineering, and costly future maintenance they necessitate.

If high-rise development is an attempt to accentuate an environmental building approach to help position Stockholm as an environmental capital, it is in all likelihood a terrible mistake. In contrast to their perceived environmental benefits, high-rise buildings are, in fact, expensive solutions requiring more not less building materials and technology when compared to other typical structures in Stockholm.

Furthermore, they generate uncomfortable wind corridors through the city and restrict sunlight from reaching the street level. In light of these factors, it is clear that the drawbacks of high-rise developments far outweigh the potential benefits of urban concentration in the inner city.

Densification and the suburbs

The clear answer to the question then, in respect of the merits of the further densification of the inner city, is that Stockholm entails more than just the inner city. Consequently, we must accommodate the pressing need for new apartments and architecture drawing attention to suburban centres and thus signalling the status and future prospects of these important locations.

This demands that significant investment is made in suburban locales to make them attractive spaces through the creation of urban values with a variety of residential choices, creative meeting places, greater densities and short travel distances. Only then will dynamic living arrangements that depart from a traditional core and periphery urban arrangement be created.

Manhattan as the vision?

From some politicians we often hear the expression "we must plan to benefit a metropolis" or "it is outdated to allow church towers to dominate our skyline." In this view, cities like Manhattan become a guiding vision of what, moving forward, we should aspire to.

Some of the original followers of the vertical paradigm are however losing interest in high-rise buildings. What is clear is that if Stockholm decides to follow the trend of high-rise development in the inner-city it will certainly be unable to compete with those cities that have been building vertically for decades. Accordingly, any attempt to oversee a transition of inner Stockholm towards high-rise development would show that we are unable to create our own vision for the future of Stockholm.

Continues p. 18

Preserve the skyline for business

The world famous skyline of Stockholm's inner city enriched by views of landmarks such as the City Hall, the City Library and Slussen Ridge prick us with nostalgia and should be preserved as such. Even so, while the emotional value of Stockholm's historical urban environment is clear to most, its contribution to overall economic success and employment is less well understood.

Research shows that economic benefits penetrate far beyond the tourism industry, as culturally and historically rich built environments are vital in attracting businesses and a prized highly educated workforce. This is evidenced by major efforts to preserve the historic environment in depressed industrial cities such as Glasgow, Barcelona, Birmingham and Singapore.

When viewed in this way, the previously mentioned high-rise development around Central Station presents a major threat to Stockholm's skyline. The focal aspects of the City Hall and the surrounding church towers will inevitably be weakened as new high-rises will obscure the gentle, varied and historic terms that characterize the current urban silhouette.

Brand on symbolism and history

Consequently, the increased level of high-rise density to the extent now being discussed in central Stockholm seems inadvisable. Instead, we must find a development plan based on Stockholm's own historic specificities, a plan that promotes the branding of Stockholm through its traditional silhouette to maintain its symbolism and history. In addition the fact that the necessity remains to preserve the city's ability to meet the unknown challenges of the future, not least, the issues of climate change and resource consumption, should not be forgotten.

Generate suburban centres

If Stockholm is to re-establish itself as a leader in urban planning then we must re-think our current development plans in respect of the inner city and its periphery. The ambition here must be to generate suburban centres with a big city 'pulse' and attractiveness that can compete with the desirability of the inner city.

To achieve this, built linkages must be developed between presently isolated suburban enclaves and greenery must be better integrated into the suburban environment instead of acting as a barrier. Furthermore, diverse housing options and a mixing of residential, commercial and recreational land-uses in suburban centres will provide pedestrian and bicycle options that can become viable transportation alternatives.

To now make major changes to Stockholm's urban silhouette, when, unlike most major cities, it has managed to maintain a relatively intact traditional character in the inner city, should be considered both arrogant and foolish. Stockholm's urban silhouette simply cannot tolerate new high-rise buildings and any attempt to build high in the inner city will come at a serious cost to its historical and cultural specificity.

By Kerstin Westerlund Bjurström, Ark SAR/MSA, President of the S:t Erik Association Stockholm. Translated by Ryan Weber