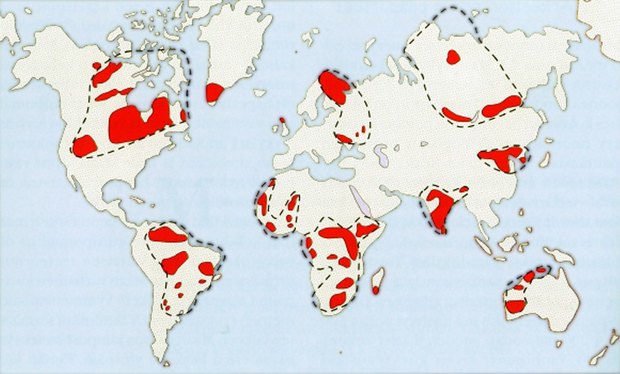

The world´s highly prospective mineral regions. Map provided by Risto Pietilä

Why did Fennoscandia attract investment in the order of 55M€ per year in the field of exploration during the period 2006-2007? The basic reasoning here is that everything, ultimately, comes down to geology. Without a suitable geology and the culture and history of mining across this region there would be no interest in investing here (Fig. Geology matters). The key issue here is the age and the evolution of the bedrock. The Fennoscandian Shield was formed together with the Canadian Shield; globally they formed the major ore field.

Crucially, the continents were joined to each other during the period of time when most of the geological processes producing the ore deposits were active. Over the passage of time various tectonic events caused the continents to drift apart separating ore provinces in the course of the crustal evolution of the Earth.

GTK-Finland

So, we are in the right area then in terms of geology but this alone is not enough. Geologists need data like medical doctors need x-rays or blood tests etc., in order to build up the information upon which further measures are based. In Finland the Geological Survey of Finland (GTK) has recorded a wide range of geological, geophysical, geochemical and GIS data over its 120 year history (Fig Data bases). This database, affording easy and reasonably inexpensive access, provides an opportunity particularly for small companies to start their exploration projects without the need for major investment.

Prior to 1994 mining and exploration in Finland was mainly carried out by state-owned companies like Outokumpu Oy and Rautaruukki Oy in addition to GTK in relation, specifically, to mapping and exploration. The risk-taking culture of small companies has thus been absent. In Canada on the other hand small companies have historically been the driving forces in producing new discoveries in the mining industry.

Access to land

Uncertainty over the issue of gaining access to the ownership of the land in Finland was removed in 1994 thus, finally, opening the door to the entry of small companies into the industry. This indeed proved to be the last significant obstacle to getting investors to loosen their purse strings. This was a significant issue in the Finnish context the satisfactory resolution of which increased trust in the investment community and thus increased the country's potential in both economic and legal terms.

After several quiet years in the mining sector the rise in metal prices in the decade from 2000 onwards certainly surprised many. Suddenly we had several advanced mining projects in Northern Finland and Northern Sweden ongoing. Throughout the period however this remained highly challenging particularly in terms of how to get the necessary number of skilled people to every project. The lack of a professionally trained workforce remains a persistent problem for all companies in this sector.

It was in the 1990s when Outokumpu, the largest mining company in Finland, started to release hints that it was going to discontinue its mining business. This triggered, perhaps not surprisingly, a discussion focussing on the need for further education.

It is quite common for Finns given the relatively short time they have spent dealing with industry and the business world, that they cannot necessarily see the wood for the trees. It is undoubtedly the case here that a retrospective view is lacking, something which generally encourages recourse to institutional 'quick fixes'. In Canada there is a saying "old mines never die, they just rest awhile". This is a good example of their more profound understanding of the mining business.

We are now bearing the bitter fruits of the short-sighted decisions taken in the 1990s as regards education in respect of the mining and mineral processing sectors. We are however lucky to have forward looking and independent-minded universities (such as those in Oulu and Luleå), which have launched new courses in mining in order to address the shortage of engineers in these areas.

EU is a global player

The EU is a major global player in the drive to upgrade the industrial sector which produces a remarkable proportion of the high tech metal products used across the world. This vast industrial sector is however based, primarily, on imported raw materials. Only a small percentage of the total amount of raw materials consumed come from domestic production sources. Figures for iron imports for example give a good idea of the situation here. This near total dependence on imported raw materials has raised questions and highlighted significant concerns in the EU Commission. As a result of this awakening the Commission has stated - in SEC (2008)2741 - as follows:

"Securing reliable and undisturbed access to raw materials is increasingly becoming an important factor for the EU's competitiveness and, hence, crucial to the success of the Lisbon Partnership for growth and jobs. The critical dependence of the EU on certain raw materials underlines that a shift towards a more resource-efficient economy and sustainable development is becoming even more pressing. It is therefore appropriate to develop a more coherent EU policy response as suggested by the Council in May 2007."

Natura 2000 is a challenge

What, however, can the EU really do here? The fact is that there are no easy solutions to the problem. It is likely that the EU will have to try to enter into long term contracts with ferrous and non-ferrous raw material suppliers while at the same time planning to increase domestic production or at least clearing the way,in terms of legal issues, for the full rehabilitation of the European mining industry in the long run. This may however have a significant impact on the way in which legal issues in respect of nature conservation, for example, are dealt with. The Commission should thus make it clear that the Natura 2000 conservation programme is simply a guideline, the administration of which could be assumed by local authorities, i.e. provincial governments as part of the environmental permission procedure.

Increase EU-supplies

What then are the chances of the EU being able to increase its own raw material supply? This, at root, is a basic question of geology. The EU actually has rather few countries with world-class ore deposits (ferrous or nonferrous). Bearing this in mind the historical rule of thumb here is that the most probable location for new discoveries is in areas where known ore bodies or old mines are already situated. As such, this does not auger well for the success of a policy calling for the breaking of EU dependence on the import of raw materials.

What else is needed here?

- Focus on the EU's mineral policy.

- Mining elevated to one of the core industrial sectors in the EU.

- Building of the infrastructure essential for the development of mining regions

- Impact assessment of the EU's raw material supply in the long run

- Positive impact on local tourism and public services etc.

- Development and application of cutting-edge exploration and mining technologies

- Mutual benefit creation for mining and tourism and the municipalities.

It is often the case that people today do not realise that the welfare of today is based on the past extraction of raw materials through hard labour. Though, currently with the benefits brought about by modern technology the end result is achieved a lot more easily and in a sustainable manner with less stress placed on the environment.

Ore and waste-rock is transported out of the open pit at the gold-mine in Kittlä. To get 1 ton of ore 9 tons of waste has been removed. Annually 10 million tons are brought out of which 1 million goes to the mill. After processing some 5000 kilos (250 liters) of gold is the net product. Photo: Odd Iglebaek

By Risto Pietilä, Regional Director, Geological Survey of Finland, Northern Finland Office