This study, initiated by the Brussels representation offices of the concerned regions, is part of theircontinued effort to profile this part of Europe. It focuses on the NSPA's unique opportunities for economic development and growth, as a counterweight to previous problem-oriented approaches. Over 50 civil servants, politicians and academics from the regions have participated in workshops where they have identified their shared ambition for the NSPA in 2020. This time-horizon was chosen to fit the next European Union Structural Funds programming period (2014-2020).

The stakeholders were asked to determine what they would like to have achieved by 2020 and to identify the most efficient public policy levers to promote these objectives. This had a twofold purpose: Externally, the NSPA regions of North Finland, East Finland, North Norway, Mid Sweden and North Sweden need to define a common position to increase their ability to influence European Union decision-making processes. Internally, the foresight study will hopefully help to increase the awareness of belonging to an area with common features from a European point of view.

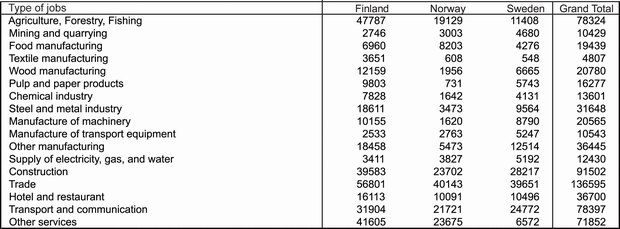

The perspective of economic growth based on current development opportunities occupies an obvious and important place in the foresight study. Mining activities in Sweden and Finland could potentially produce thousands of new jobs; growth perspectives in the North Norwegian fish farming sector are also important; throughout the NSPA, there is evidence that winter and summer tourism could be increased enormously with the help of integrated local product development. Based on these possibilities and on the economic performance levels of the last ten years, public policies in the NSPA cannot be justified on the basis of supporting lagging or weak economies.

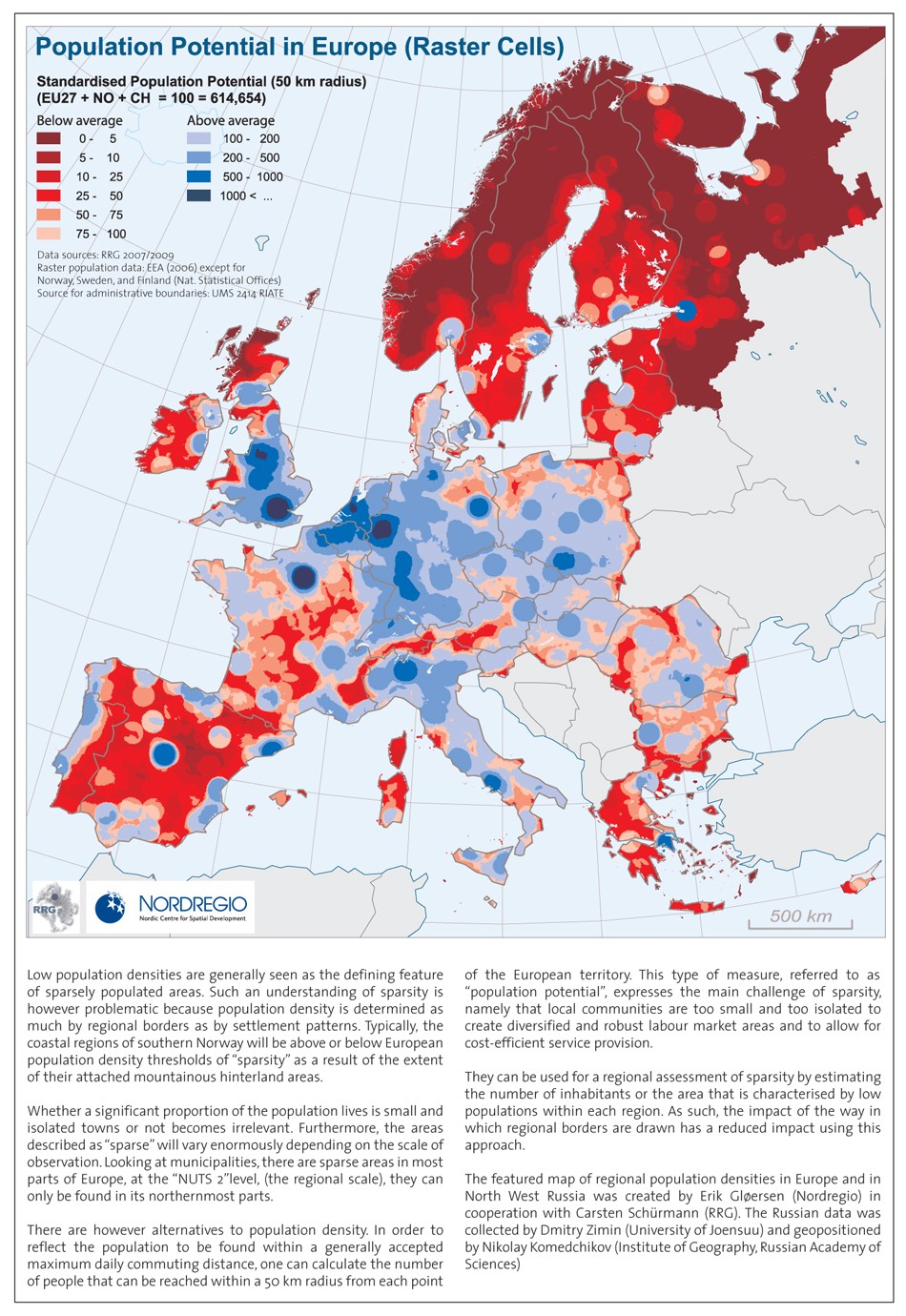

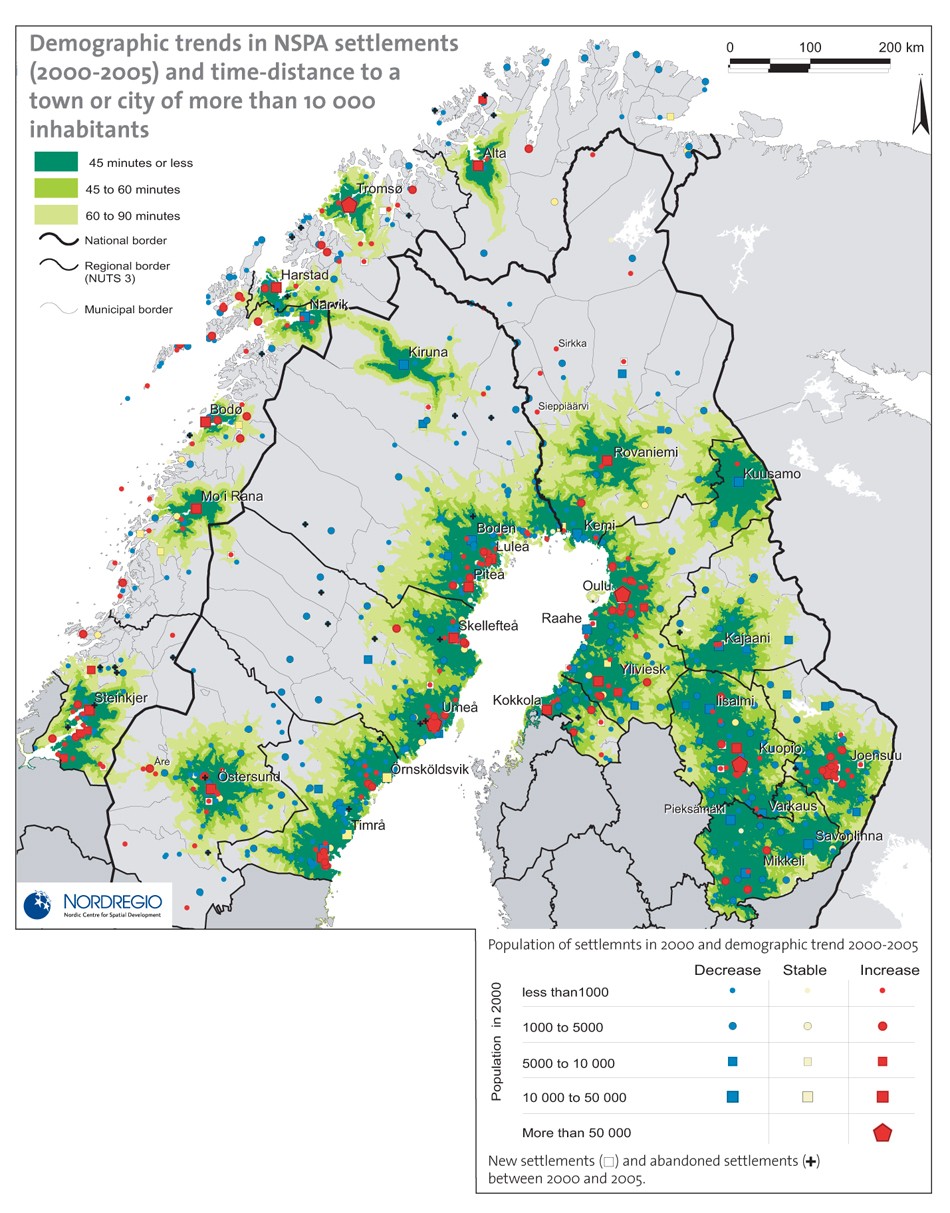

The concern is however to ensure that the income generated by these activities should help to ensure a socially and ecologically sustainable future for the NSPA. In spite of the development possibilities the majority of NSPA municipalities experience continuous population decline. Up to 2007, many NSPA entrepreneurs mentioned recruitment difficulties as the single most important limiting factor of growth in their company. Many parts of the NSPA are therefore insufficiently attractive for reasons that are independent of their economic performance.

The under-representation of women in most of these areas can be considered as both a symptom of and a causal factor in these imbalances. Similarly, in-migrants from outside the Nordic countries are significantly fewer in rural NSPA municipalities than in comparable areas in the rest of Norway, Sweden and Finland. Many NSPA localities therefore still need to demonstrate that they can offer a social environment allowing for a contemporary modern lifestyle and the personal and professional fulfilment of all their inhabitants. They have obvious assets in this respect, in terms of secure and cohesive communities and high quality natural environments. But there are also some critical weaknesses, especially in terms of access to services and the perception of certain localities.

In this respect, the development of more knowledge-intensive activities throughout the NSPA is then more than just a tool to increase the added value and robustness of local economies. It is also a strategic measure to modify the perception of local communities, which would be able to pride themselves on being at the forefront of technological development within specific industrial niches. Numerous examples of good practice in the NSPA demonstrate the efficiency of such strategies. The objective for the NSPA then is to demonstrate the advantages of small-scale research and development activities developed in close cooperation with local industries. This implies a positioning in respect of Research and Development policies favouring major centres of excellence. A recurring idea here is to establish a fund based on income from raw material extraction in the NSPA to finance local R&D initiatives.

The increased geographical spread of R&D functions and knowledge intensive activities however does not imply that higher education should follow a similar pattern. There is a general consensus that higher education institutions need to be of a certain size to function efficiently. Combined with the objective of raising the education levels of the population, this implies that youth will increasingly need to leave their place of birth in the NSPA at least for the period of their studies. Permanent policies to encourage return migration and the in-migration of young graduates of other origins are therefore required.

In terms of access to services, the success of the Tornio-Haparanda shopping precinct, whose development was triggered by the opening of an IKEA store, shows that the NSPA is different from other parts of Europe. The mobility patterns of a population prepared to travel hundreds of kilometres to access such services allow for alternative regional development models. A restricted number of strategically positioned centres, potentially distinct from the major cities, could function as purveyors of commercial services to the entire NSPA. This would significantly change the development perspectives of individual towns and settlements.

Such wide-ranging mobility, together with long daily commuting distances however means that the NSPA is heavily dependent on fossil energy. As such then this type of investment cannot be envisaged throughout the NSPA. Furthermore, the contemporary and modern lifestyle upon which NSPA stakeholders are building their development vision requires access to air transport. The higher ecological footprint per inhabitant in NSPA regions compared to more densely populated areas however needs to be weighed against the renewable sources of energy, mineral and other natural resources that would be made unavailable if the NSPA were to be depopulated.

The very extent of these resources however makes it possible to envisage infrastructure developments that would otherwise be unimaginable. The Bothnia railway project exemplifies this. While the transportation needs of exporting industries justify this major investment, it will also allow efficient and sustainable connections along the Swedish coast from Sundsvall to Umeå. Similar types of 'win-win' situations could be identified in other regions, for example along strategic East-West oriented transportation axes connecting the NSPA to North-West Russia. Along the Norwegian coast, maritime corridors could play a similar role. The NSPA regions need to develop a long-term settlement strategy based on these possibilities particularly in respect of improvements in their transportation infrastructure.

The foresight study has also shown that NSPA regions generally do not want to be viewed as peripheries. They can boast numerous sectors of activity in which they are at the forefront of innovation, including information and communications technology, biotechnology and forestry. They would prefer to profile themselves as an interface to Russia and to the Arctic rather than as an area far from the "European core". And they look upon extractive activities and processing industries as sources of income and expertise that should be mobilised to build a new knowledge-based economy.

This requires that the public authorities play a more pro-active role in channelling regional energies and in ensuring that private initiatives contribute to the overall ambition of creating a sustainable future for the NSPA. The NSPA stakeholders would also like to involve the European Union more as a strategic partner in this ongoing process.

By Erik Gloersen

(former) Research Fellow, Nordregio