In recent years, however, the concept of polycentricity – and its inherent expectations, diverse understandings and interests – can also be seen to have increasingly trickled down to the regional level, in particular with a view to guiding spatial development 'within metropolitan areas', which we in the following call 'intra-metropolitan polycentricty'.

No grand theory

No grand theory

In a literal sense, the term 'polycentric' indicates that a spatial entity consists of multiple centres. The term does not however clarify what kinds of centres (centres of a transport axis, for housing, certain economic activities such as retail, industries etc.,) are in focus here, so that various notions and starting points are conceivable when discussing polycentricity with spatial planners and policy makers.

The available literature pinpoints what we already know and what is difficult to assess or even to measure. There is however little hope any time soon for the emergence of a grand theory explaining, specifically, what intra-metropolitan polycentricity is and how it differs from monocentricity.

What is clear however is that there are different dimensions associated with the notion of intra-metropolitan polycentricity along with the observation that our metropolitan areas today have seen very different development-paths and dynamics (due to varying historical, geo-political and socioeconomic circumstances) which results in various challenges in terms of physical planning but also in the development and growth of appropriate governance systems.

Hence the notion of intra-metropolitan polycentricity must be related to the specific context-sensitivity in which our metropolitan areas are embedded.

Four different dimensions

Due to these variations one can argue that the concept of polycentricity in general entails (at least) four dimensions each of which should be carefully distinguished when discussing it. The analytical-descriptive dimension should be mentioned first, i.e. to describe, measure and characterise the current state of a spatial entity by pinpointing how far a country or a metropolitan area can, for instance, be said to be 'polycentric'.

Secondly, the concept can be understood in a normative sense which could help for instance in re-organising the spatial configuration of such an entity (i.e. either to promote/create polycentricity or to maintain/utilise the current polycentric setting).

Thirdly, when talking about spatial entities one needs to clarify their spatial scope (e.g. the city-level, the city-regional, the mega-regional level or even the national or transnational level).

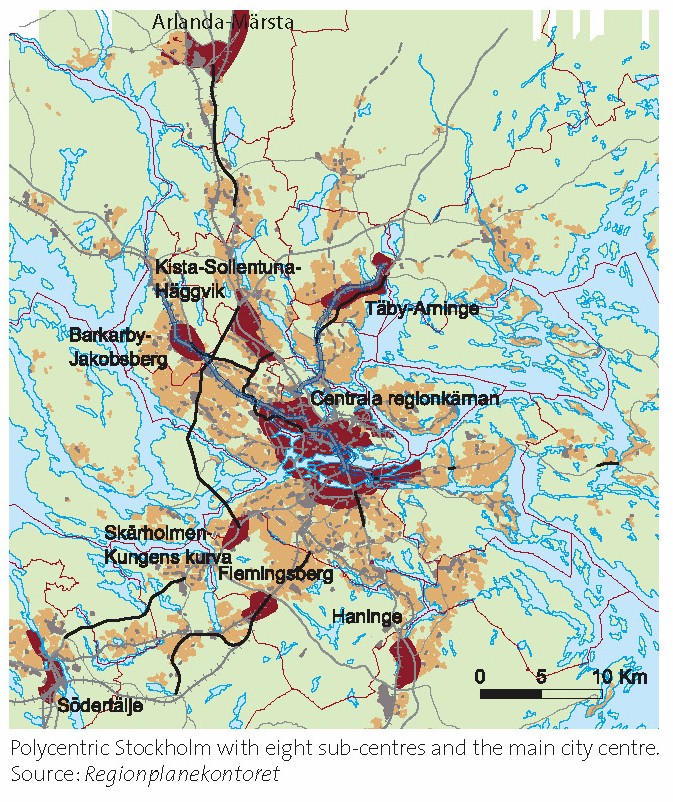

On closer inspection, the concept also challenges our understanding of centres within metropolitan areas as it can be related to either their roles or functional ties (i.e. their inter-relations) or their specific morphological forms (i.e. the structure of the urban fabric as it is illustrated in red on the map below). This differentiation between a functional and a morphological understanding of polycentricity constitutes the fourth dimension.

The work of the METREX Expert Group

On the initiative of the Office of Regional Planning of Stockholm County Council an Expert Group on intra-metropolitan polycentricity (IMP) was set up within the METREX Network of European Metropolitan Regions and Areas. The Expert group, whose work was supported by Nordregio, worked together for a period of about 18 months and have just published their findings in a report.

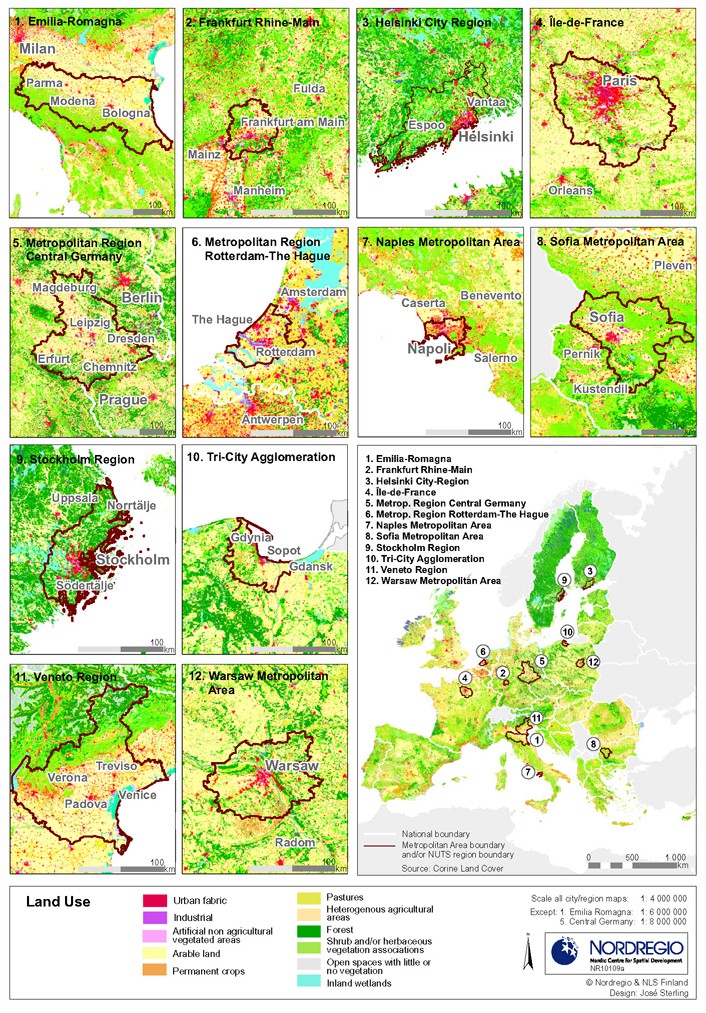

The spatial planners in the Expert group from twelve metropolitan areas across Europe (see map below) explored three thematic strands deemed to be closely related to the concept of polycentricity within metropolitan areas. These were a) Metropolitan Governance and the Implementation of Plans and Policies, b) Urban Sprawl and Climate Change Response and c) Economic Competitiveness and Functional Labour Division between Centres.

The central objective of the Expert Group was to identify major challenges, to reflect current methods, practices, routines and debates and to share lessons and experiences with regard to the performance, applicability and implementation of the concept of polycentricty in the respective metropolitan areas represented in the group.

Generating a mutual level of understanding

One of the Expert Group's major concerns was the generation of a mutual level of understanding in respect of the specific and highly context-sensitive polycentric setting of each of the twelve metropolitan areas. As a consequence of this discussion within the group twelve brief portraits, one for each of the participating metropolitan areas, were elaborated.

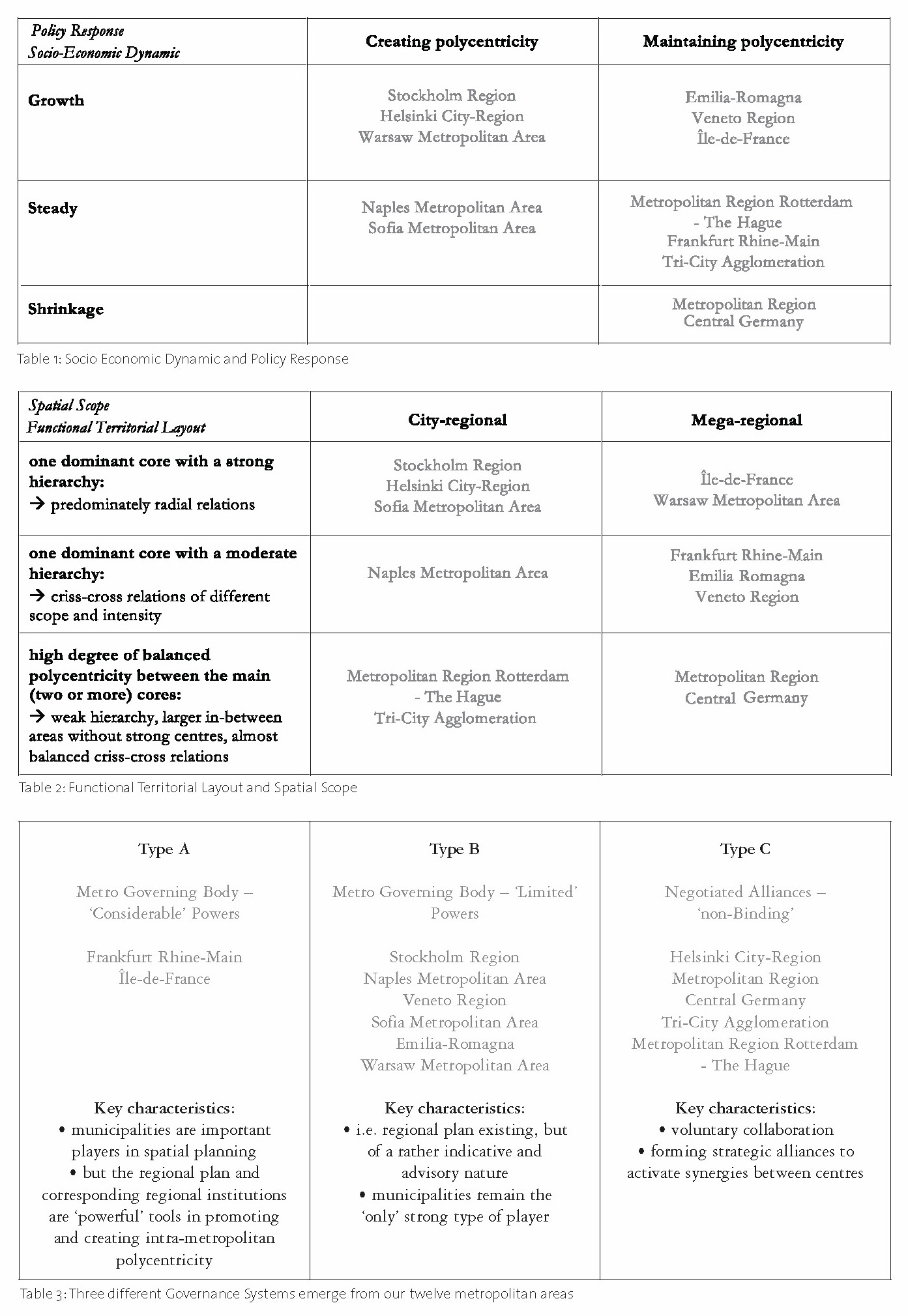

Based on these portraits, the understandings that emerged from the academic debate on the notion of intra-metropolitan polycentricty (IMP) and on discussion within the group, five basic characteristics (socio-economic dynamic, policy response, functional territorial layout, spatial scope and governance system) for the differentiation of intra-metropolitan polycentricity (IMP) were identified.

This allowed us to develop three typologies for the respective metropolitan areas represented by the Expert Group. These typologies proved useful in categorising their different qualities in order to understand these polycentric metropolitan areas as dynamic systems and, most importantly, to make it easier to undertake meaningful communication about them. See table 1 to 3 on page 26.

The policy response is certainly of central importance here, since it indicates the overall strategic direction of the metropolitan area at hand in this respect.

The two Nordic examples (Stockholm and Helsinki) are both growing metropolitan areas in terms of population and jobs, and as such both experience growing demand for housing and work places. The concept of polycentricty shall consequently help to create or develop further 'new centres' as nodal points for urban development. This emerging structure shall also be supported by a corresponding transport system.

Within the Expert Group, however, a small majority exists who use the concept of polycentricty rather to maintain or better utilise the existing polycentric structure through better cooperation and the coordination of policies between the different centres or cities respectively with the aim of encouraging positive synergies.

Major conclusions from 12 metropolitan areas

The major conclusions of the work of the Expert Group have been derived from the inputs generated by its members through a number of questionnaires and mutual discussions in the course of five workshops. This means they are solely based on the spatial planners' perceptions, reflections and experiences. In total there are four central messages that this international Expert Group want to address, which can be understood as a commonly shared baseline in respect of 'intra-metropolitan polycentricity' (IMP):

1) There are a number of key preconditions for the application of IMP, such as to understand that IMP is a long-term strategy, which means that the involved stakeholders need to be patient. There is also a clear need to understand market mechanisms better, particularly their potential territorial impacts as being a key driver for creating or maintaining polycentricty within metropolitan areas.

In addition, commonly shared views in respect of key terms and concepts are required as well as better tools to communicate intentions in relation to what IMP is expected to deliver. In line with this the stakeholder's mental maps have to be enlarged in order to understand our polycentric metropolitan areas as networking urban configurations as well as the essential interplay between different levels (e.g. municipal / city-regional / national).

2) The capacity of the governance system matters. There is a need for clear strategies and solid instruments to manage the different interests/agendas/territorial logics of the many stakeholders involved. Since IMP is not only a spatial concept; it also entails a specific governance capacity and response. It requires cooperation, coordination and mutual understanding at different levels. Here it is essential, however, to ensure that the entire metropolitan area develops consistently according to 'one single IMP concept'.

3) IMP can help to combat urban sprawl and thus to respond to climate change in a positive manner. Here there are three key issues to be considered: A further densification of some specific and carefully selected centres in accordance with the development and protection of the green structure ('polycentric compactness').

Secondly, higher densities must be linked with higher centralities (e.g. in terms of urban amenities, labour opportunities). Thirdly, as a kind of backbone for this picture, a polycentric transport system has to be developed that corresponds to the shape of the urban fabric and to the level of demand in terms of accessible centres along with solid transport axes and nodes in order to generate a reliable and efficient transport system that covers the entire functional metropolitan area.

4) IMP can help to promote economic competitiveness and target-oriented labour divisions between centres. In this sense it can be supportive in reconciling competitiveness and territorial cohesion policies within metropolitan areas while at the same time minimising agglomeration disadvantages (such as congestion and high land rents) through the decentralisation of economic activities. But if political and organisational coordination is lacking, IMP can lead to increasing transaction costs.

Download the full report

Table 3: Three different Governance Systems emerge from our twelve metropolitan areas

By Peter Schmitt, Senior Research Fellow and Hans Hede Regional Planning Office, Stockholm County Council