In addition to the military activities undertaken and the infrastructure provided, it used to be a complete town, with the usual civilian infrastructure such as shops and laundries. After ten years, only a few faded Russian language signs remain to remind us of the former presence of Soviet troops. It had in effect become a ghost town. Indeed, the state of neglect was such that nature was about to reclaim it for wilderness. Rabbits and deer provided the only inhabitants now, while foliage grew wildly with much of the built environment already covered in a layer of moss and grasses.

The German authorities had not yet found a solution for the potential reuse of this particular site. The soil was heavily polluted by fuel oil and it is probable that a significant amount of live ammunition, mines, and other dangerous substances remain strewn across the site, either hidden underground, or simply lying in the undergrowth.

True, the area had been used in an innovative civilian way. Movie companies have hired it for action movies, where this kind of environment was needed. Indeed, it proved to be rather popular as the movie companies were often given carte blanche to blow up buildings and build new installations.

Conversion continues

This example is no isolated phenomenon. In fact, more than 3000 former military sites of different sizes and purposes are currently subject to civil conversion in the Baltic Sea Region. This equates to an area the size of the Swedish island of Gotland and the Estonian island Saarenmaa together or approximately 6000 km2. Imagine these beautiful islands totally covered by abandoned barracks, empty garages, dilapidated infrastructure, and rusty and abandoned military equipment.

Conversion is not however only a challenge for those countries, regions and municipalities, where former Soviet troops were situated. The same process is taking place in all of the Baltic Sea countries, though in different forms and for different reasons.

There is moreover, no sign that this process is drawing to a close. Instead, the restructuring and modernisation of the defence forces continues apace, with more and more military sites being put up for closure.

Click on picture for more information

A shared responsibility?

Several emergent challenges result from base closures. Often they are of a negative character from the perspective of the local communities upon which they impact. In the former "Western" countries in particular, military conversion has often led to a reduction in jobs and purchasing power coupled with a reduced tax base, causing huge problems for the municipalities concerned. In many cases moreover such bases are already located in structurally weak areas.

One of the lessons of this process has been that the state has to take responsibility for helping the municipalities, particularly where the labour market is fundamentally dependent on the defence forces. Any approach that sees the Ministry of Defence in question simply withdraw its activities, leaving the particular municipality alone to tackle the new situation, is patently bound to fail. In Sweden, for instance, this problem has been partly solved by the commitment of the state to relocating some public agencies or parts thereof from Stockholm to the affected areas.

Environmental problems

Particularly in respect of former Soviet military sites, serious environmental problems often emerge in relation to such base closures. Such problems are often both difficult and expensive to deal with. In Estonia for instance, the most serious environmental challenges have been harbours with sunken ships, airbases with heavy fuel contamination and shooting ranges with unexploded mines. Another feature of these sites is that the buildings and other infrastructure are usually in such a bad condition that they cannot be easily renovated for reuse without major investment.

As such then it is the new EU Member States in particular that need support in disposing of the consequential damage resulting from military use and in developing former military facilities and sites for civilian use.

Former military horse stables in Potsdam, Germany, have been converted into an office building.

New uses for empty barracks

Even if the infrastructure is in good shape physically, as is mostly the case with the "Western" conversion sites, it is not always easy to reuse the infrastructure that has been "inherited" and originally planned for an altogether different kind of activity.

Even if the infrastructure is in good shape physically, as is mostly the case with the "Western" conversion sites, it is not always easy to reuse the infrastructure that has been "inherited" and originally planned for an altogether different kind of activity.

The initial idea in Finland, for instance, was that the Ministry of Defence would simply transfer the properties to the local municipality. However, in many cases the local authorities were unwilling to take on the responsibility for such sites, or it proved impossible to agree on the price. One solution here was that the state apparatus tried to use the former military properties for its own purposes, such as offices, universities, and educational centres etc.

This did not however prove to be practical as the general trend in state policies in many countries includes an ideological desire not to further expand the public sector. It is often difficult then to find rational solutions. Moreover, in many cases, a number of open legal questions have emerged in respect of the issues of ownership and availability, which further hinder the process of conversion.

The need for national conversion programmes

It has also become clear that conversion entails costly planning and management procedures. One good solution or 'best practise' in this respect is to establish a development company to take care of the actual conversion process. For instance in Sweden, a state-owned property agency Vasallen AB was founded in 1997 to convert former military sites and to construct a new identity for them, after which such areas will be sold to private investors or used by public authorities. This has proved to be a practical solution at least for Sweden.

Other strategies are also possible. In some countries, such as Poland, re-use has been encouraged by promising flexible terms of payments and tax concessions for limited periods in order to attract potential private buyers.

In any case, the overall lesson is that a well-developed national conversion programme is needed in order to successfully manage the conversion process. This should encompass the whole range of related issues and ensure the commitment of all levels of administration, while also including non-state actors and the private business sector. Thus far however, only a minority of the Baltic Sea countries have such programmes in place.

The promise of conversion...

Conversion should not predominantly be seen negatively in the context of the potential challenges it poses but rather more positively in light of the potentials it creates. It offers, if it is properly planned and managed, interesting opportunities for municipalities and other public authorities to innovatively solve existing land use and housing problems, while it may also bring totally new businesses or other activities into the region concerned, such as a new educational facility or a new tourist attraction. Furthermore, one should bear in mind the fact that the conversion of military sites into civilian use is not at all a new phenomenon. Such activities have taken place in all eras.

Indeed the very premises in which Nordregio is based, and the whole beautiful island where it is situated, Skeppsholmen, in the very centre of Stockholm, used to be a naval base. Today the island is one of the main tourist attractions of the city and hosts several museums, art schools, institutes, annual festivals, youth hostels, and restaurants. Similar examples can be found in every major city in the Baltic Sea Region, and, for instance, old military fortresses are often the most celebrated objects of cultural heritage in many places.

Two waves of post-Cold War conversion

A rough divide between the waves of recent conversion in the Baltic Sea Region and in Europe as a whole can be made. The first 'wave' was directly related to the end of the Cold War. This period lasted from 1990 to 1996, during which time the Soviet troops left their bases in the Baltic States and the former Warsaw Pact countries. During the same period, most of the allied forces were withdrawn from former West Germany and many other European NATO countries, leaving large areas to be abandoned without function.

Since 1996, this initial withdrawal period has been followed by an adaptation of the various national armies to the new post-Cold War conditions, both in terms of new threat assessments and alliances, and technological and organizational modernisation. In many Western European countries a major strategic shift from territorial defence to international crisis management, such as peacekeeping or peace enforcement has taken place. This has resulted in the downgrading of national defence forces and their related infrastructure to better match their new 'political' tasks. In addition, NATO enlargement has also contributed to this development, since a tendency has emerged for US forces in particular to be relocated from the old NATO countries to the new ones.

By Dr. Christer Pursiainen, previous Senior Research Fellow at Nordregio

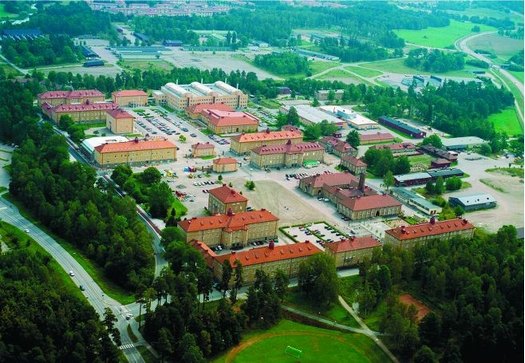

Vasallen Garison in Linköping, Sweden, has been tranformed into houses and offices.