Fish farming may become an important survival strategy for many small communities. Here the village of Trongisvágur in the Faroe Islands

The production of salted and dried fish has helped create and sustain wealthy communities since medieval times, with the Mediterranean countries as the major markets, but with South America and Africa emerging as new options in the 20th century.

Technological developments in the global transportation of frozen products undoubtedly moreover contributed to the maintenance of this position after WWII and on into the latter part of the 20th century.

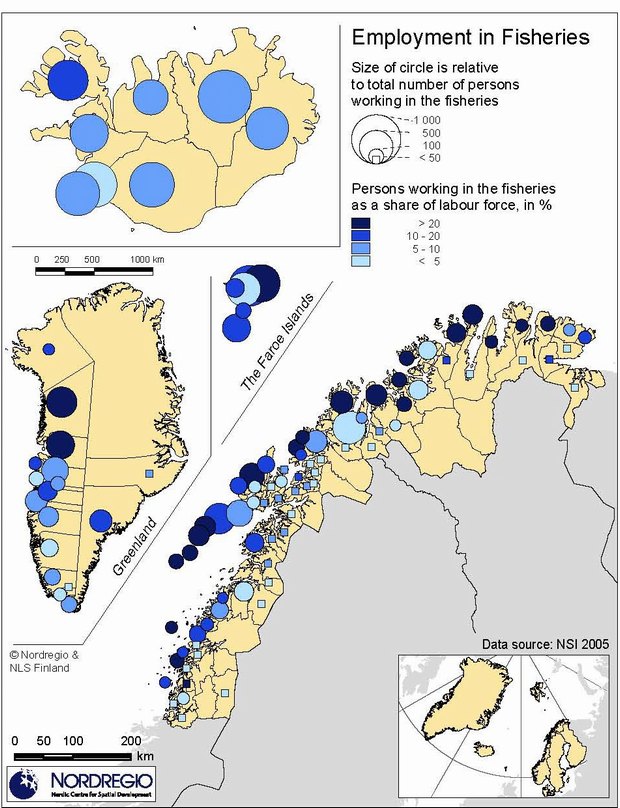

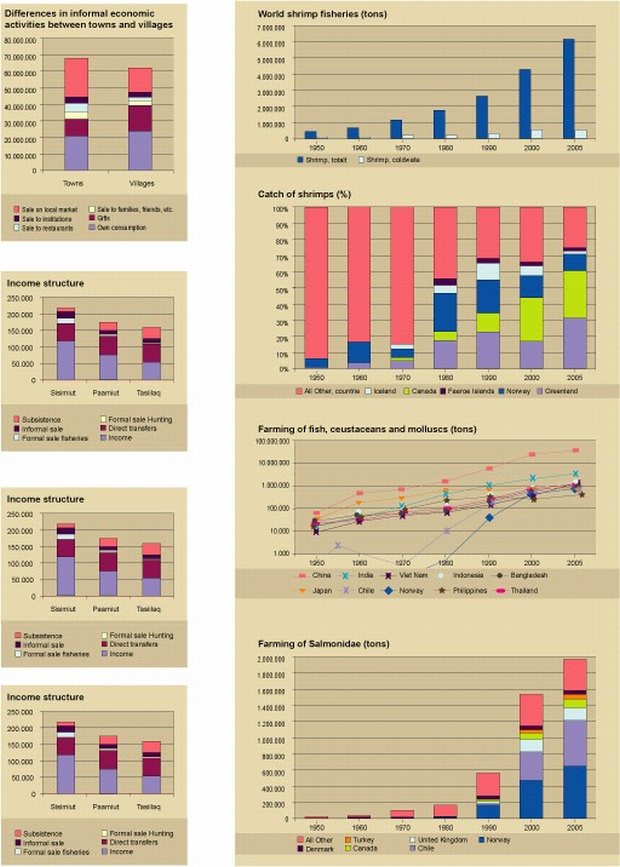

Since the 1970s, however, the historical position of the West Norden region has been increasingly challenged as the fisheries industries in other parts of the world have also gone global. While global harvesting of crustaceans and demersal and pelagic marine life has increased, from 11.5 million tons in 1950 to 66.6 million tons in 2005, the West Norden share of this total has been reduced from 15% down to 7% while the 6-fold increase in the total global marine harvest has had consequences for world market prices. Indeed, by 2005 the market price for fish had been reduced to 70% of the price in 1975.

Other challenges have also emerged. The resource base of the North Atlantic is fluctuating due to natural variation in currents and sea temperatures while in several instances fish stocks have been threatened by over-fishing.

While the global price problem is basically unmanageable, the challenge of over-fishing has been addressed through regulatory measures. The introduction of the 200 mile EEZ in the 1970s enabled a national focus on maintaining a healthy fish stock, while international agreements regarding the management of migratory stocks in the 1990s have limited the potential for human-induced cata-strophes. The "Law of the Sea" and a number of inter- and supra-national organizations such as ICES (International Council for the Exploration of the Sea) have also helped to increase the viability of marine resources.

These ongoing changes have not however totally wiped out the fishing industry and the fisheries-dependant communities of the North. The actors across the North Atlantic region have long understood the challenge facing them while continuing to focus on what is important, namely, continuing the global marketing approach, and doing it by means of very different national approaches.

The advantage of early adopters

With the dwindling of fish stocks the potential to ´farm' fish became ever more attractive. Fish farming is not a novelty. Worldwide farming of fish in ponds and cages has occurred for centuries. But large scale production in a more industrialized form in open water cages was something new in relation to the global market. And it enabled the fish farmers to focus on high quality and high value species such as Salmon. Consequently, fish farming was grasped as an important alternative – or rather addition – to traditional fishing.

In the North Atlantic region Norway and partly also the Faroe Islands, given the existence of certain favourable conditions, were early adopters here. The farming of Salmon in cages in sheltered fiords where currents could provide a good production base gave some obvious advantages, including that of making use of the relatively warm waters of the North Atlantic flowing up the Gulf Stream.

As shown in figure 4, commercial seafood farming has increased from a level of 100,000 tons in 1950 to more than 50 million tons today. China has always been the major player in this industry, but Norwegian farmers managed to position themselves positively at an early point in time. And by being early adopters the Norwegians were able to take advantage of the initially high prices for farmed products, primarily salmon. As shown in figure 2, global production of farmed salmon took off during the 1980s, and has been expanding ever since.

Currently however the industry is in the doldrums as the current price level of farmed salmon is down to half that which could be obtained when the industry first emerged.

During the first three decades of the industry's development Norway domi-nated global production figures but over the last decade it has been challenged by an array of new entrants to the market.

The primary challenge has come from Chile, where the same favourable natural conditions as those in Norway exist, and where production costs are substantially lower. Moreover, during the next decade Norway's position will be challenged further, and its position as lead producer will undoubtedly be lost.

In this light then instead of continuing as a direct producer, Norway is currently in the process of positioning itself as a global producer of equipment for fish farming. While in both Norway and in the Faroe Islands increasing focus on alternative species has evolved in an attempt to once again take advantage of early adopter-status in relation to a high value activity.

The competition today is however much fiercer today as compared to 40 years ago. In addition, the competitive advantage of being situated close to the resources seems to have diminished, as it is generally acknowledged that there is a need to bring these activities out of the region and towards the global centres of activity where labour costs are lower and environmental concerns less pressing.

Consumer and market interaction

The fisheries sector includes much ore than just fishing. The development of new methods and especially the development of new types of equipment, in response to changes in the production line from sea to consumer, have been the key characteristics of the fishing industry in Iceland.

When the processing of fish moved on-board the trawlers themselves Iceland was among the first to develop processing, scaling and packing equipment which could work under the rough conditions of a North Sea gale. And when the market demanded fresh products, again companies in Iceland provided tanks suitable for the transportation of chilled products as well as ship-to-shore communication systems which could provide the producers with precise market information, and the marketing sector with precise information regarding the status of the catch.

Consequently these changes in the fisheries industry have been followed by the parallel development of a new industry focusing on the production of equipment for fishing and processing, thus providing new jobs and income opportunities in the region.

Being able to "read" the market and thus respond quickly to consumer's demands has also been an important factor in the marketing of fish products. Since the 1980s Greenland, through the Home Rule owned company Royal Greenland, has been the key player in connection with the production of coldwater shrimp.

In 1990 their market share of this product was around 25% thus ensuring that they were one of the major players in this industry. The market for shrimp, however, was confronted by a huge increase in the production of warm water shrimp, and a concomitant increase in the production of farmed shrimp. Conse-quently the world market price of coldwater shrimp was reduced to less than a third of its pervious value within a few decades.

Like most other fishing companies in the North Atlantic region Royal Greenland had also based their production model on the bulk production of fresh or frozen products with limited processing taking place.

Consequently, they were hit by the fact that maintaining high value production required 'value adding' through a higher level of processing. Moreover, when moving from bulk to 'value-added' products, producers need to remain in close contact with the market.

Even though the internet and other modern means of communication boast of diminishing distance, this is a field where distances actually matters. It may seem to be an anachronism to focus on "being there", but maintaining a precise sense of the changes in market demands and customer habits is a chal-lenge, and requires personal involvement.

Consequently Royal Greenland started acquiring processing capacity within the European market, for instance by buying up capacity in Denmark and in Germany. It enabled the company to remain in touch with these changing demands, and – at least for a while - positioned the company among the worlds 10 largest producers of seafood products.

Involvement in distant fisheries

When resources are dwindling or market prices plunging a potential objective for fisheries-dependent communities and companies would be to look for resources beyond their own region. Distant water fisheries have been an option which Iceland has followed for several decades, in order to maintain its high level of fishing activities.

Initially the targets have been the sea areas close to Iceland, for instance the "loop-hole" in the Barents Sea, and the "loop sea" between Greenland, Norway and Iceland though fisheries opportuni-ties in other continents, for instance in Africa, have also been pursued. Around 25% of the value of the fisheries industry in Iceland stems from distant water activities, providing the basis for the generation of extended revenue beyond the limitations of local resources.

The long term viability of these activities is, however, determined not only by the agreements which can be made with the owners of the resources, but also by the fact that the stock limitations render this approach a time-limited activity at best.

A new alternative has thus emerged in the context of involvement as a supervisor and manager of activities in a development perspective, and here Iceland has managed to establish a favourable position for itself.

For example, since 1998 Iceland has hosted the United Nations University Fisheries Training Programme (UNU-FTP), which offers training in various areas of the fisheries sector to practicing professionals from developing countries. The programme assists developing countries in promoting fisheries as an important role in the national or regional economy, including the development of an export-oriented fisheries sector.

Next steps?

Distant water activities and the supervision of new economies in their endeavours towards the development of their own activities may address the problem of industry sustainability in the short term but may not be enough to create a more permanent solution ensuring sustainable economic activities in former fisheries dependent communities.

Similarly it can be questioned to what extent the companies and the products involved in this global rebranding process are losing their 'North Atlantic identity', and to what extent further development is based on the interests of the region, or more prosaically, on the interests of the companies themselves on the global market. Undoubtedly however this new global approach has bought the region some time to think through what its next steps will be.

* All figures are based on data from FAO Fishstat database.

* Calculation of change in price level from 1975 to 2005 based on export prices according to Fishstat and regulated according to changes in consumer price index for fish products.

Text and all photos:

References

ARNASON, Ragner and Lawrence FELT (eds.), 1995, "North Atlantic Fisheries: Successes, Failures and Challenges". An Island Living series, volume 3, Institute of Island Studies, Charlottetown, PEI

FAO, 2007, "The state of World Fisheries and Aquaculture". Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation, Rome.

LEES, Kathryn, Sophie PITOIS, Catherine SCOTT, Chris FRID & Steven MACKINSON, 2006, "Characterizing regime shifts in the marine environment", Fish and fisheries, 2006, 7, 104–127

RASMUSSEN, R.O., Tom GREIFFENBERG, & Gorm WINTHER, 2008, "Regionalpolitik, Regionalisering og Planlægning. Centrale problemstillinger i den regionale udviklingsproces". Inussuk - Arktisk Forskningsjournal, Nuuk, Grønland. (Forthcoming)

THE WORLD BANK, 2006, "Aquaculture: Changing the Face of the Waters. Meeting the Promise and Challenge of Sustainable Aquaculture". Report No. 36622 – GLB, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Washington.