However 'fuzzy' the concept of innovation may be it undoubtedly requires a solid knowledge base. Consequently regional access to R&D-related investment, private and/or public research facilities, highly-skilled labour in the knowledge intensive industries sector and a favourable production environment, are all viewed as being crucial in relation to the drive for innovative and economic success.

Regardless of the fact that the Nordic countries generally perform well in international comparisons on innovation, competitive innovation poles integrating all those components backed by high-quality cooperation and partnership links are not the rule everywhere. As such, regional innovation endowments, as well as economic structures more generally, remain highly diverse across Norden.

From studies already undertaken1 it is also evident that large R&D investments and/or innovative success do not necessarily yield economic progress and higher growth rates. Despite this trend a recent study2 points to the fact that innovation is rarely dealt with in a territorial manner by innovation policies in the Nordic countries.

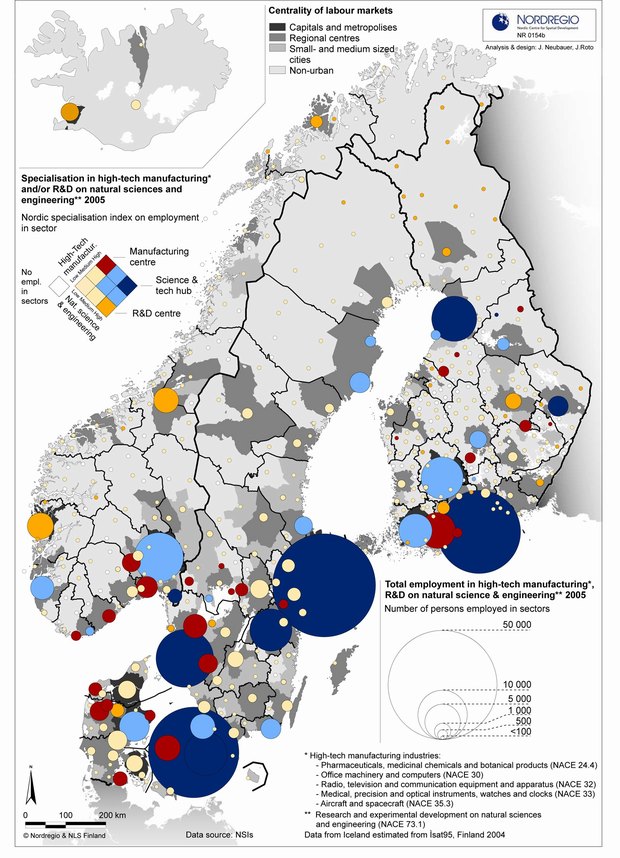

If innovation policy, however, wants to play a stronger role in accommodating regional competitiveness and territorial cohesion, it may then need to invest in more regionally differentiated approaches. This should also include further encouragement of alternative types of innovation in regions lacking the potential to compete on the basis of technological innovation alone. Indeed, in relation to the high-tech sector, which is undoubtedly innovative and beneficial to the Nordic countries as a whole, the reality is that this sector actually directly benefits only a few regions as is illustrated below.

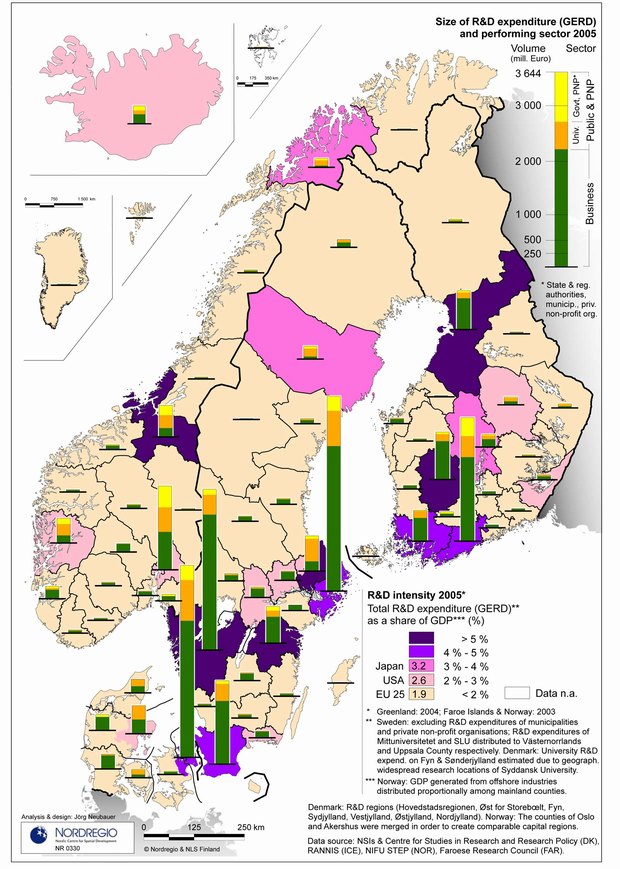

Sweden and Finland are the World's top investors into R&D and the only European countries already exceeding the ambitious Barcelona target for 2010 of at least 3% of GDP to be spent on R&D. In contrast Norway's investment is not even half that of its neighbours. In Sweden, Finland and Denmark roughly two out of three investment shares are funded by the private sector. In Norway and Iceland however, such activities are funded equally from both private and public sources. This financial mix generally corresponds to the composition of actors undertaking the R&D activities though regional variations remain significant (Figure 1).

The reality is that most Nordic capitals and metropoles invest in R&D with a public-private blend that matches their respective national expenditure mix but with a stronger emphasis on market-oriented research and development in the private sector.

A number of important Nordic regional centres with a university however lack sufficient private engagement to effectively complement public R&D investment. Examples here include regions such as Sør-Trøndelag and Troms in Norway, Västerbotten and Uppsala in Sweden and Pohjois-Savo and Pohjois-Karjala in Finland. In contrast, several more peripheral regions attain their expenditure budgets almost exclusively from the private sector.

The majority of Nordic expenditure on R&D it should be noted is primarily channelled into a few major regions. Indeed, roughly one third of the Nordic countries total expenditure in this area finances R&D in the five Nordic capitals. In Denmark the capital area receives almost the entire sum of national expenditure in this sector for itself. Adding the large Swedish R&D hubs of Västra Götaland and Skåne to this group leaves slightly more than half of the budget to be shared by all other remaining regions. However, some selected regional centres invest a considerably higher share of their GDP in R&D. In Finnish Pohjois-Pohjanmaa (Oulu) and Swedish Uppsala the commitment to R&D in this regard is nearly twice that of their respective capitals.

A major drawback with such inter-national and interregional comparisons based on nominal R&D expenditure volumes, priced in Euro, is however that they tend to disregard the effect of variations in real purchasing power across different countries and regions. Research and development is a labour-intensive activity and thus wage levels become decisive in respect of how much research equal amounts of R&D expenditure can finance.

Implying the same high-skilled labour could be made available in any Nordic region if demanded, the same nominal expenditure would probably buy more research in Helsinki than in Copenhagen or, in the other case, more research in Umeå than in Stockholm.

Hence the real value of Danish and Norwegian expenditure on R&D is possibly lower as compared to Sweden and Finland as is the case for expenditures in capital regions. Notwithstanding this however the overall picture described above hardly changes.

The major share of the expenditure which is utilised for research and development is in the high-tech sector with a strong market orientation. Not surprisingly the locational pattern of this industry largely coincides with that of the R&D investments depicted above. When opposing the Nordic labour markets' specialisation in, on the one hand, research and experimental development in natural science and engineering, and on the other, in high-tech manufacturing, a geographical picture polarised along the urban hierarchy emerges (Figure 2).

High-tech innovation poles of scale and strong on both competences (dark blue) are few and are almost exclusively capitals joined by the Swedish metropoles and the northern technology stronghold of Finnish Oulu. Alongside these science and tech hubs some additional, considerably smaller poles with rather varying strengths (light blue), can be found in almost every Nordic country.

Contrary to text book geographic theory however few additional scattered labour markets in the periphery and in the vicinity of the hubs succeed in embarking solely on high-tech production (dark red). Moreover, high-tech related stand-alone research of relevant scale (orange) is hardly conducted beyond the high-tech innovation poles disregarding Bergen, Trondheim and Tromsø (Norway), Viborg (Denmark), Kuopio (Finland) and of course Reykjavik (Iceland), all of which house a major technical university.

As is apparent from the discussion above, the potential for Nordic regional eco-nomies to develop further in respect of technological innovation, varies substan-tially. Indeed, many smaller regions will need to find their own paths to prosperity that may not include high-tech speciali-sation and may in fact profit from embarking upon alternative ways of promoting innovation in, for example, the public service sector or tourism. For those regions then a more regionally differentiated innovation policy would undoubtedly help.

By Jörg Neubauer, previous Senior Research Fellow at Nordregio