The goals of the Lisbon strategy have also significantly influenced the elaboration of the EU Structural Funds Programme for the period 2007-2013. This 'regionali-sation' of the Lisbon Strategy sends a clear message: its goals can only be met if each region maximises its capacity to produce economic growth and successfully develops its endogenous regional potential.

Of course, one simply cannot expect all regions to contribute on equal terms to the achievement of the Lisbon strategy as they do not possess the same levels of economic and social potential. In the Nordic countries, the capital city-regions of Stockholm, Copenhagen and Helsinki have acted for many years as the economic engines of their respective countries, highlighting the ongoing process of economic polarisation in those countries.

However, recent trends show that capital regions in Norden are no longer the undisputed winners in terms of economic growth. Figures recently published by Eurostat show that between 2000 and 2005, the regions of Uppsala (4.2%), Hallands (5.0%), Västerbotten (4.4%) and Norrbotten (3.9%) all had an average yearly economic growth superior to that of Stockholm (3.7%). Similar patterns can be found in Finland where no less than 11 regions are currently out-performing Helsinki (Uusimaa region).

In spite of this, it is easy to see that the capital regions remain the main contributors to the various national efforts in respect of economic growth due to their larger size. However, the contribution of other regions should not be overlooked, and indeed require a better understanding of how best to support the regional effort to contribute to overall EU Strategy. Moreover, the fact that all EU regions are now eligible for the Structural Funds, the main Community financial instrument targeted at the regional level, is a sign that all regions should be supported, to different degrees and extents, in order to improve their capacity to adapt to a globalising, rapidly changing economic environment.

Yet, in order to help in the design of better adapted financial instruments, it seems necessary to provide clearer evidence to the policymakers regarding the particular strengths and weaknesses of each region.

Traditionally, regional performance has been understood in terms of economic development, due to both political orientations and limited data availability on other matters. But while economic development is undoubtedly an important facet of regional development, the latter should not simply be reduced to the former.

Other dimensions, such as the employment structure, the demographic structure or the level of social and educational capital can be decisive elements in elaborating regional development strategies. In order to grasp this complexity of what the notion of regional development actually entails, it is necessary then to develop new methodologies for defining new typologies of regional performance. A recent study, commissioned by the European Parliament and led by Nordregio, provides a possible way forward in this respect.

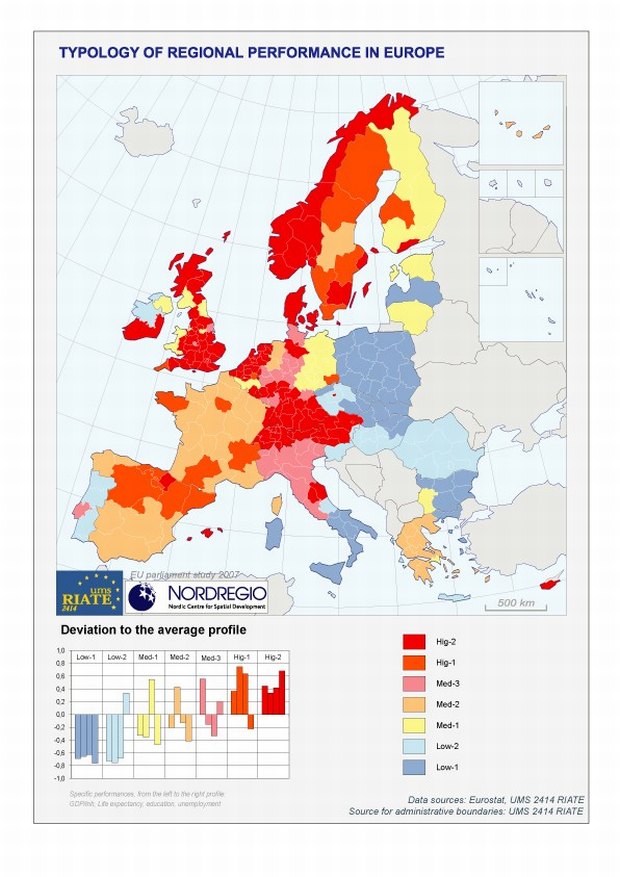

The scientific solution developed by the research-team uses statistical classi-fication methods applied to a limited set of indicators, enabling the production of a more comprehensive typology of regional performance in Europe. The four indicators analysed highlight a specific aspect of regional development: GDP per capita (economy), life expectancy at birth (demographic structure), educational level (education) and unemployment rate (labour market conditions). The typology is constructed such that the variations within each type of region are smaller than those between them. One can thus suppose that each type of region represents, to some extent, a rather homogenous family of regions.

The typology (see map) reveals seven main types of regions in Europe, each showing a particular combination of socio-economic characteristics. For example, the picture in the New Member States, i.e. the countries which entered the EU after 2004, is strongly differentiated.

If many regions belong to the category with the lowest overall performance (Low-1 type in blue), characterised by a low performance in all four indicators, numerous other regions, for instance in Romania, Hungary, Slovenia or the Czech Republic, perform rather well with regard to unemployment, and thus belong to a separate category (Low-2 in light blue).

Indeed, some capital-city regions in the New Member States even belong to the highest category (Hig-2 in red). This is the case for both Bratislava and Prague.

From a European policy perspective this suggests that the various families of regions should be supported using an adapted combination of new and currently available regional and sectoral policy instruments.

For the Nordic countries, the picture also remains rather differentiated. The whole of Norway and Denmark (Denmark is considered as a single region here) belong to the highest category; as do the capital regions of Sweden and Finland.

However, other Swedish and Finnish regions belong to categories which suggest that they have specific structural deficiencies which should be addressed: the higher unemployment rate in Western Finland and most Swedish regions (Hig-1 in orange); good educational level, but poor on other dimensions, for most Finnish regions (Med-1 in yellow); and high life expectancy, but poor on other accounts, in Norra Mellansverige region (Med-2 in light orange).

Consequently, in the Nordic countries, different regions should be supported in different ways in order to best help them overcome their specific structural deficiencies.

In conclusion, this article aims to highlight, on the one hand, the need for the research community to utilise and develop a broader scientific basis with a view to providing a more relevant evidence base in respect of regional development in Europe, and on the other, the need for the policymaking community to broaden their perspectives on the necessity of utilising a multi-dimensional approach to regional development strategies.

1 The author would like to thank the partners of the study, especially Claude Grasland and Catherine Zanin (CNRS, France), Carsten Schürmann (RRG) and Tomas Hanell (Eurofutures Finland).

For more complete information on the study, the final report is available online:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/hearings/20070625/regi/study_en.pdf