What will the demographic situation in the Nordic countries look like in 2030? This scenario takes its point of departure from the recent Nordregio report Demographic Challenges to the Nordic Countries. The scenario described here points to several positive aspects while also highlighting some negative trends. The main point here is however that the so-called "demographic challenges" so often discussed at the rhetorical political level are not really about demography at all, but actually relate to imperfections in the workings of Nordic labour markets.

Growing populations

Contrary to the current alarmist concerns in respect of a focus on declining populations, the populations of the Nordic countries will have increased by 2030. According to the projections made by the national statistics offices, the Nordic population will increase by 9.7 per cent as compared to current levels.

|

Populations in million inhabitants

|

| Country |

Present |

Projected 2030 |

| Denmark |

5.4 |

5.7 |

| Finland |

5.2 |

5.4 |

| Iceland |

0.3 |

0.4 |

| Norway |

4.6 |

5.4 |

| Sweden |

9.1 |

10.1 |

| Total |

24.6 |

27.0 |

|

Source: National Statistics Offices

|

A population projection made by Nordregio shows that the total population of the Nordic countries will increase to 30.3 million, with an annual growth rate of approximately 0.4%.

Population concentration

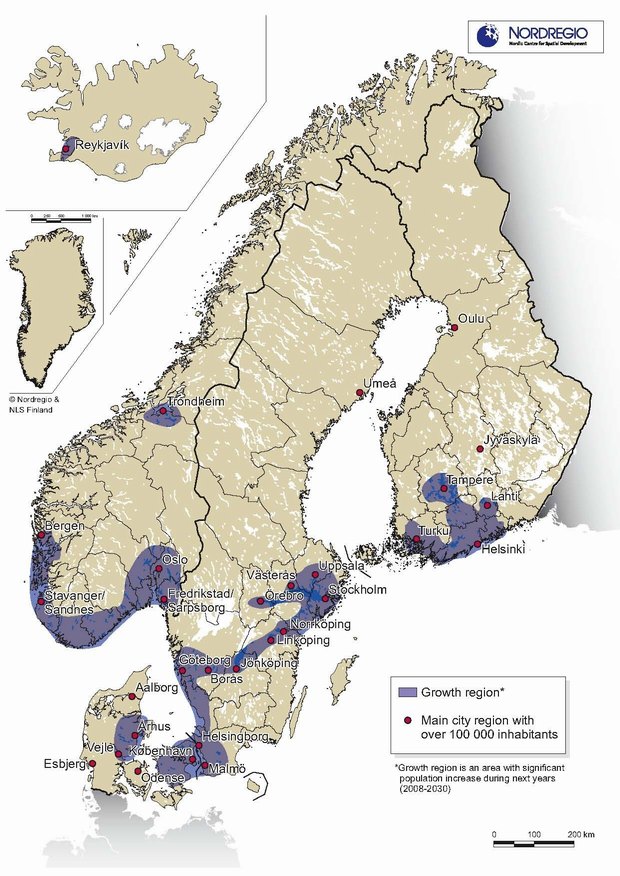

We will also see a geographical concentration of the population to metropolitan and urban areas in the coming 20 years. Rural and peripheral parts of the Nordic area will have to face up to declining population levels, while urban and metropolitan areas will experience a population increase. In sparsely populated areas depopulation will become a reality. The Nordic regions currently showing a negative population development will, by 2020, have decreased and this decrease, in general, will smooth over time.

To put this polemically, there will be more people and cities and towns will continue to grow in the shaded "population corridors" (see the map). Outside these "population corridors" population decline and depopulation will be a fact of life. By 2030 the mountains and valleys of Norway will be tourist-resorts. Hardly any Finns will live in the woods. Northern Finland will be as depopulated as Northern Sweden. As the old people in Northern Sweden die out, so will the towns and villages in the inland areas.

Higher fertility rates

The retreat of the welfare state, with social security systems supporting us 'from the cradle to the grave', has led to a revival of the family. As a result, fertility rates will increase as compared to the current levels. An increase in nuptality (the marriage rate) can also be expected. The coming generations will likely display preferences other than those chosen by the ´baby-boomers' from the 1940's in respect of family and children.

Since the 1960s we have seen a regional convergence in fertility rates across the Nordic countries. Around 2020 this convergence trend will be replaced by one of increasing divergence in regional fertility rates. To some extent this can be explained by the fact that an overwhelming majority of the population will live in a rather limited geographical area in the Nordic countries.

Life-expectancy

The Nordic countries have, for a long time, been world leaders when it comes to high life-expectancy levels and low mortality levels. One explanation for this is, in an international comparison, the existence of a well-functioning healthcare system and government subsidies for the real costs of medical treatment.

In 2030 this situation will have altered markedly due to the increasingly polarised nature of socio-economic development and growing problems with obesity. A larger share of the 'real' costs for medical treatment will thus have to be paid by the individual, since taxes can only be raised to a certain level (and that level was reached long before 2030!). The rich will stay healthy while the poor will get sick more often.

Emigration countries

By 2030 it is not just well educated high-income earners who will leave the Nordic countries due to the high tax-burden. Increasingly those with immigrant backgrounds will also have done so due to the discrimination they face and the problems that arise in relation to the imperfect nature of the labour market. The second and third generation immigrants who have invested in tertiary education will simply not accept being unemployed or taking jobs in peripheral or rural parts of the Nordic countries.

Since most people in the Nordic countries speak a Nordic language, English plus at least one other language they are potentially well placed in relation to the international labour market. The large Spanish speaking group in the Nordic countries with roots in Latin America will probably be more welcomed in Spain; German speaking persons will be welcomed in Germany and Austria etc. North America and Australia will also open their doors to new – and highly qualified - labour. These countries can, and will, be able to pay for this labour. The failure of integration policies in respect of persons with an immigrant background in the Nordic countries will be painfully visible in 2030.

Today we already see small migration flows of retired persons from the Nordic countries to Mediterranean Europe and Thailand. This kind of migration will have become common by 2030; pensioners will constitute an economically strong consumer group and will spend their money where they get the most value. Why spend the winters in a miserable climate in the North of Europe when it is possible to relax in the sun?

Labour shortage

Although the Nordic countries witness a continued population increase labour shortage problems will increase over time. These problems are related to imperfections in the workings of the labour market however, not to an actual shortage – relative or absolute – of persons of working age. Mismatch, low geographical labour force mobility, a segmented labour market, the "insider-outsider" dilemma and the problem of "locking in" a labour force are some of the problems affecting the supply of labour. The effects of the failure to reform the Nordic labour markets at the beginning of the twenty-first century will thus, by 2030, be extremely painful.

Few labour immigrants will by this time move to the Nordic countries. The current trend in international migration will be the norm in 2030: short-term contracts with a temporary stay in the country of destination. After the contract is fulfilled the migrant worker returns to his/her family in their country of origin.

By Daniel Rauhut, previous Senior Research Fellow at Nordregio