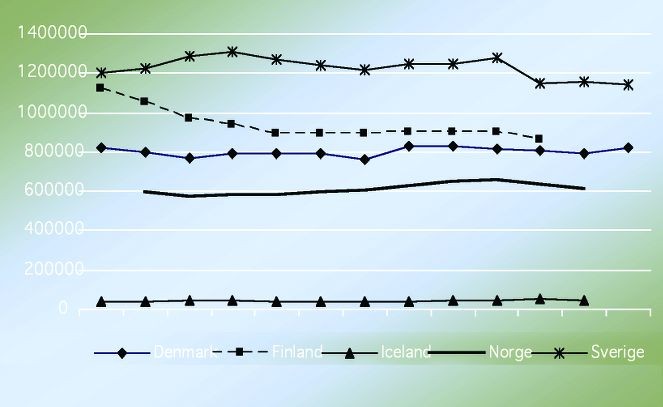

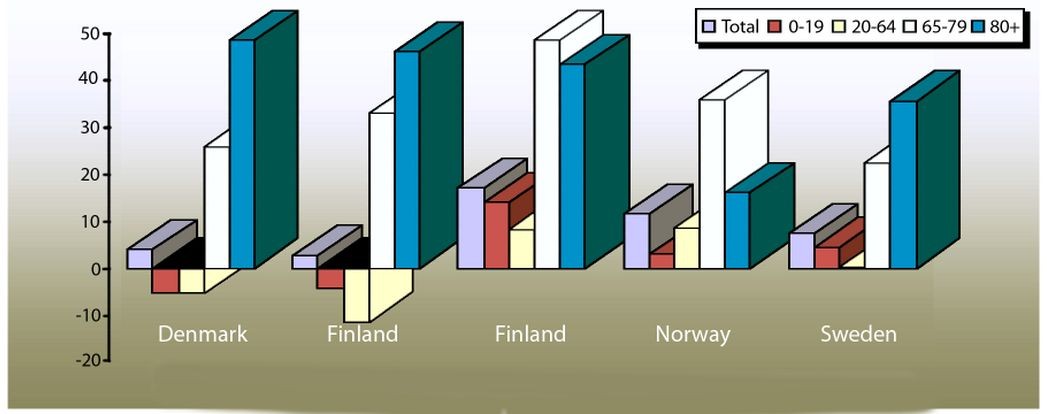

Figure 3: The number of persons in the Nordic countries who are not in the labour force 1995-2007.

The share of excluded persons in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden 2007/2008 as

a share or the labour force

Simulations and scenarios for the period 2020-2030 show that while some rural and peripheral regions will experience a significant population decline more urban regions will experience the opposite. The result is that regional population imbalances will be accentuated. This population imbalance calls for a new regional development policy designed for a post-industrial society to be im-plemented. The regional development policies used today are firmly rooted in the industrial economy and as such are now obsolete.

The Nordic populations will continue to grow at a national level 2010-2030. While Denmark and Finland will experience small decreases in the population of 0-19 year olds, these age groups will continue to increase in the other Nordic countries (in Sweden the increase will be 0.2 %). The massive increase for the two oldest age-groups can partly be explained by starting from lower numbers.

The Nordic populations will continue to grow at a national level 2010-2030. While Denmark and Finland will experience small decreases in the population of 0-19 year olds, these age groups will continue to increase in the other Nordic countries (in Sweden the increase will be 0.2 %). The massive increase for the two oldest age-groups can partly be explained by starting from lower numbers.

Mismatch in the labour market

Since the regional population imbalances are an already ongoing process, the labour market problems – e.g. mismatch and labour shortage – will become very challenging indeed even without demographic ageing. Future demo-graphic ageing will however aggravate these labour market problems.

In most Nordic countries voices have been raised regarding the issue of labour shortage, employers have expressed difficulty in finding the labour they need, and immigration is needed to fill the vacancies. In a market economy however there is really no such thing as a true labour shortage. If you want more of something, you can pay more and have it.

"Labour shortages" distort the efficiency of the labour market. A central condition for an efficient labour market is that the matching process between vacancies and job searchers functions well. Information and search costs are central in this process. The labour market is frequently troubled with matching problems and these problems are often related to structural changes in the economy at branch or sector level.

The matching efficiency on the Nordic labour market has decreased, i.e. the mismatch has increased, in recent decades. Examples here include the fact that geographic mobility has decreased. Further, that the labour force rejects low paid low status jobs. Thirdly, that employers reject some groups of labour such as 50+ years, single mothers, young adults and, immigrants). For those rejected the risk of unemployment is very high, and as a consequence, the risk of social exclusion is also high.

Exclusion from the labour market

To this group of excluded persons the long-term sick and early retirees must be added. The general estimate here is that about 50% of the long-term sick could return to the labour market if appropriate rehabilitation measures began early enough. In addition, the number of early retirees could also be reduced.

Officially 1 in 6 persons in the working ages belong to this list of 'the excluded'. In fact, the figures are probably higher: e.g. involuntary students and domestic workers ought to be included as well. In figure 3 the total number of persons in the working ages - but not in the workforce - is illustrated. For the Nordic countries together this group constitutes more than three million people. The group also contains early retirees, housewives, students and persons who declare themselves as non-working (persons who are excluded from the sickness insurance register but have not yet 'retired').

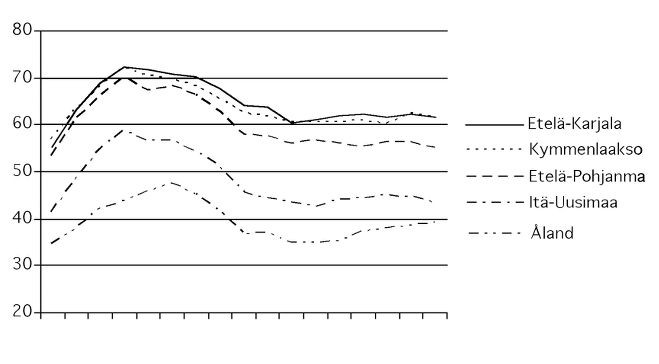

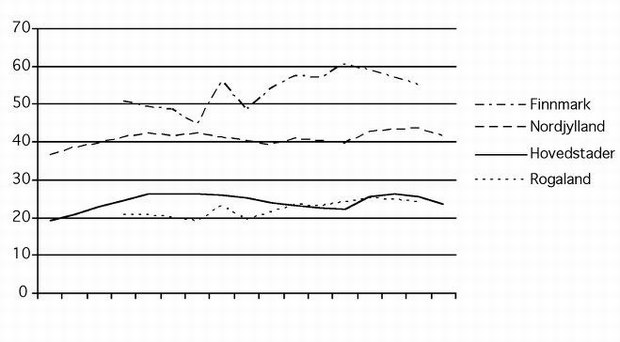

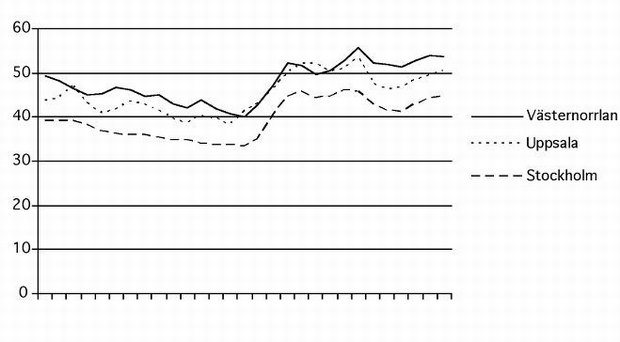

The regional potential labour supply as a share of the labour force is actually quite large in most regions. The total number of persons on long-term sickness leave, unemployed or otherwise economically inactive, although they are in the working ages, thus constitutes a potential labour supply. In Finnmark and Västernorrland 1 in 3 persons in the working ages is not working and thus is not in the potential labour supply. In Kymenlaakso, Etelä-Karjala and Etelä-Pohjanmaa almost 2 in 5 persons in the working ages are not in the potential labour supply.

With such a potential labour reserve it is difficult to see how we will run out of labour due to ageing and a relative decline in the population aged 20-64 years old. Rather, this very large potential labour supply actually indicates a misuse of the labour currently available.

It is remarkable that peripheral regions with a "labour shortage" also show the largest potential labour supply. This indicates that the supply of potential persons to the labour force is not the main problem, but that the institutions of the labour market have failed to allocate labour efficiently and thus have failed to fill the vacancies available.

In figures 4-6 the "wavy" behaviour of the regional potential labour supply is clearly visible, something which indicates an impact of economic cycles on the potential labour supply; this is to be expected since e.g. unemployment varies at the same pace as the economic cycles (economic boom – low unemployment, and vice versa etc). Consequently, short-term economic fluctuations, the functioning of national labour markets and their institutions etc., appear to determine the regional potential labour supply. Since this potential labour supply is so large it must be analysed more thoroughly in future studies; if used properly, the Nordic countries will not have to fear any labour shortage in the future.

Utilise the potential labour supply?

Much of the problem lies in the fact that poduction is now occurring in a post-industrial economy while the labour market and its institutions are still wedded to the concepts of the industrial economy. Labour market policies, often governed by 'vested interests' remain too rigid; as a result unemployed workers have only weak incentives to move to other parts of the country for work. The challenge is to adjust the existing system so that it better advances efficiency and sharpens labour market incentives.

One of the most efficient ways of changeing peoples' behaviour in the desired direction is to reward them economically when they behave 'well', and to make them pay if they are not. This is an interesting point of departure when discussing how to utilise the potential labour reserve, but it is also of course highly controversial.

Furthermore, the potential labour reserve can only be utilised if there is a real demand for the kind of labour which this group can provide. If employers continue to reject e.g. persons 50+ years, immigrants, single mothers, young adults and the former long-term sick no fundamental changes will take place.

Potential policy approaches

Stimulating fertility remains an important long-term policy here. Child allowances do not, however, seem to stimulate fertility and the child allowance in itself is relatively low compared to the real costs of having children. Since people have a tendency to dislike taxes, tax-reductions for the second child (and even more for the third child etc.,) may stimulate fertility rather more. Many persons would prefer to spend the money on one more child rather than paying the same amount in tax.

Immigration policies must include a settlement policy – if labour is needed in the rural and peripheral areas, and if immigration can fill the vacancies, immigration should be allocated to those areas. Today about 2/3 of all immigration is allocated to the metropolitan areas in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.

Economic incentives to move to rural and peripheral areas must then be created. New university graduates could reduce their student debts if they move to, and remain in, some areas of the country for a number of years (as is the case in Norway). In addition, tax instruments could also be used – if you live in some parts of the country you pay less in government tax and if you live in densely populated areas you pay more. Regions (län, fylke, maakunta etc.,) should be able to tax the income earners; using their taxation rights they should be able to attract the inhabitants they would like to have by offering them relatively favourable tax conditions.

Mobility in the labour market must increase, both geographically and professionally. One way to achieve this may be to liberalise the labour market. The "flexicurity regime" (Denmark) may also be worth considering in other countries. To reduce this mismatch an active labour market policy, including vocational training and education, should be further developed and designed to meet the needs of regional labour markets. A liberalisation of the labour market and an active labour market policy are seen as complementary policy tools; both policies are needed.

Administrative reforms can be useful, the actual territorial division of competences is important but the question of rational service provision, e.g. should schools, medical care etc., be run by the municipalities or the government, has emerged as the major focus here.

Time perspective and governance

Thus far, policies designed to improve labour market imbalances in the Nordic countries have been implemented on the national level while welfare service provision has been a regional or alternatively a predominantly municipal task. Labour market imbalances are embodied, predominantly, on the regional level thus requiring a regional approach. Within this context then, we can we expect that welfare service provision is also to a larger extent a regional and not a municipal challenge?

Broadening the scope of regions, there is a danger that poor policy coordination between the national and regional levels may lead to the delivery of contradictory policy actions. National regulations and frameworks decide the most significant aspects of the ageing agenda, such as questions related to retirement, to the structure of welfare services and the labour market. The provision of welfare services is sensitive to ongoing administrative reform processes. Therefore national-regional policy harmonization is a crucial element of policy delivery. The major challenge then is to find ways to modify the welfare system in order to encourage efficiency and improve labour market incentives.

The current policies used to address labour market problems were designed to solve the problems of an industrial economy at the national level. This is the reason for the moderate results achieved in solving the problems of the post-industrial economy on a regional level. Since the problems in the post-industrial labour market are different to those of the industrial labour market, the policy tools must be re-designed to deal with these new issues. This means that new ideas, new 'trains-of-thought' and new long-term visions are needed to design future regional policies while the traditional labour market institutions must be adjusted to the needs of the new post-industrial reality.