Leaving the port of Vardø. Note white ´radar-ball' to the left. Town-hall with pyramide-roof in the centre. Photo: Odd Iglebaek

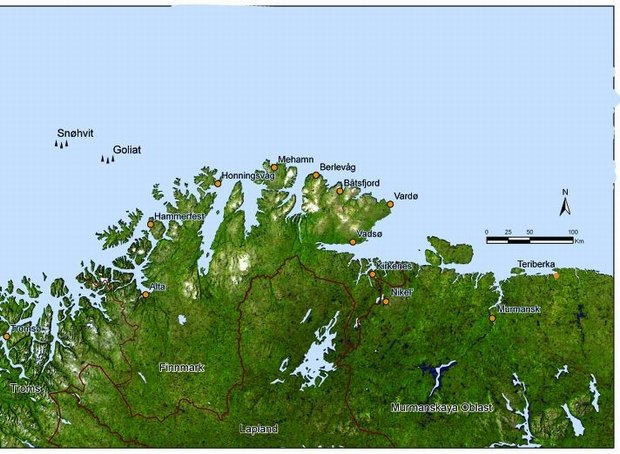

The climate of Finnmark, the most northerly county of Norway, is tough. The Varanger-peninsula points out into the Barents Sea. No trees grow on the coastline. There are hardly any islands. To the north, the mountains roll down into the sea. To the east there are many beautiful beaches and endless wind. Maximum water temperature in summer is said to be eight degrees Celsius. Sailing further to the North you meet the Polar-icecap.

The availability of natural resources, first and foremost the fish in the sea and the possibility for reindeer to find grazing, has enabled people to live here over the centuries. It has also, at least until very recently, been fishing together with mineral resources (mines) that have been the economic bedrock of any larger community in the region.

In recent years more and more fish are being caught by large trawlers and frozen at sea. Via the huge freeze-store in Kirkenes fish is transported to China, de-frosted and processed. The low wages paid makes the process cheaper. There-after it might be re-frozen and re-exported to the European market. In the 1960s and 1970s Finnmark used to have filet-factories in almost every port. Today there are only a few left. The rest have closed down or gone bankrupt.

Mr. Oddgeir Danielsen is the Port Director of Kirkenes. As a municipal employee for him it is also an important task to promote the town as an excellent place for trade and investment. He makes no secret of the fact that he really enjoys this part of the job:

– Yes, it is fascinating and we are in many ways at the centre of events. Contact with the Russians has generated a lot of jobs and trade, the king-crab fishing trade has grown rapidly, there are also plans to reopen the iron-ore mines at Sydvaranger, and finally there is a good chance that we well become a major port for the supply and servicing of the Shtokman gas-field.

The area around Kirkenes was a common Norwegian-Russian district until 1826 when borders were settled. In 1906 the iron-ore mine at Bjørnevatn (AS Sydvaranger) opened. At that time, Kirkenes only had a few houses and a church (kirke) but it quickly grew into a town of several thousand inhabitants.

Historically, it was the discovery of nickel in Petsamo in 1921 that generated the most devastating developments in this part of the high north. The ore was some 30-40 km south of Kirkenes, at that time on the Finnish side of the border. It soon became clear that Petsamo had the largest deposits of nickel in the world, and through the war the Soviet Union made certain it gained control over Petsamo. That is a control Russia still maintains. To extract the precious metal the mine-town Nikel was developed. Even today the nickel-mines continue production at high speed and still generate huge profits.

Russia's only ice-free harbour in the west is Murmansk, some 200 km east of Kirkenes, This, combined with the availability of the area's precious metals, was (and still is) of course of the utmost strategic interest. The discovery of oil and gas in the region has placed these issues even higher on the international agenda.

During the later stages of World War II Germany had some 300 000 soldiers in Finnmark, four times the population of the county. Kirkenes alone had 30 000. In the autumn of 1944 however the town and most of the surrounding county experienced the full ravages of war. Soviet bombers flattened Kirkenes. To make matters worse, almost every building in the county was burned in the scorched earth policy employed by the retreating German troops.

After the war Finnmark was rebuilt, partly with the help of the US-Marshall Plan. Demand for the iron from AS Sydvaranger was rapidly increasing. The 1950's, 1960's and 1970's proved to be ´a golden era'. Kirkenes received asphalted streets before any other town in Finnmark, built a large indoor swimming pool, as well as a hospital and an airport. It also became a key centre for the Norwegian military.

In the 1980's, however, the mining of iron-ore in Kirkenes, even with continuing state-subsidies was no longer profitable enough. From a workforce of some 1200 people, the large open-air mine was significantly scaled down. In 1996 mining came to an end completely.

– All that was left was basically a huge hole in the ground. The future indeed seemed bleak, but the collapse of the Soviet Union was soon to change all this. The borders which had been more or less sealed during the cold war were opened and localised trade mushroomed, explains Mr. Danielsen.

– Kimex the new shipyard built in the centre of the town is very important in this context. They specialise in repairing Russian fishing-vessels. We daily have 30-40 Russian trawlers here. They come to change crew and to buy food and fuel. We also have the largest warehouse for frozen fish in the north. In total this generates trade to the value of one billion NOK every year.

– Why do the Russians come here? First and foremost, because Norway has so little bureaucracy compared to Russia. In Kirkenes we can start unloading a Russian trawler twenty minutes after it has moored. In Murmansk they will have to wait for two days, maybe two weeks. Think of an oil-rig in need of a service. The cost to hire these rigs is 700 000 USD per day. Guess what waiting-times mean to these guys? And with construction soon starting at Sthokman, well you see what we are planning for he says laying out maps of the massive planned expansion of Kirkenes harbour- and port-facilities.

To develop Sthokman will take time. Probably production-start will be earliest in 2020. The process calls for vast amounts of steel, cement equipment and manpower. All of this has to be transported, supplies re-fielded, vessels repaired etc. Sthokman is also too far off-shore for ordinary helicopter-flights. Logistics issues will be very important.

At least three communities thus far hope to gain from the fruits of the new industry. In addition to Kirkenes, the Russian village of Teriberka and the small Norwegian town of Vardø have also declared their new Barents-ambitions.

Vardø is probably one of the most windswept towns in the world. The history of the place goes back to 1307, when what was the most northerly fortress in the world was built there on the island of Vardøya. By 1700 it had developed into a trading centre. Both Finnish and Russian merchant ships called at this ice-free port. The fortress was extensively rebuilt during the course of the 18th century. Today all of the tourists on Hurtigruten are taken on a half hour guided tour to study the stronghold, while the ship waits at the quay. Like the rest of Finnmark, Vardø was extensively damaged at the end of World War II.

The military role of Vardø has continued into the modern era. In 1998 a major US radar system was installed. The huge balls protecting the equipment are easily visible on top of the towns' hills. Officially the US has claimed that the purpose of the radar station is to track space debris. Most people, however, see it as a spy-system focused on Russia.

In 1982, Vardø was connected to the mainland by Norway's first underwater tunnel, more than three kilometres long. The population about half of which is of Finnish decent had risen to 2600 by the turn of the twentieth century. By 1970 it had increased again to 4500, while today it is back down to around 2250.

– It has been downhill for a long time now, explains veteran-fishing Social-democrat politician Thor Robertsen. – Every year, in fact 2-3 million kilos of fish is landed here in Vardø only to be sent along the coast to factories in neighbouring Båtsfjord. It is ironic particularly in light of the fact that there was a brand new 100 million NOK fish-factory opened here in 2003, only for it to be closed 12 months later. Robertson is also a member of the Expert committee for the High North appointed by the Government of Norway a couple of years ago. In particular the committee is tasked with contributing to ideas for growth and jobs in the region.

– Are the central authorities contributing enough, do you think?

– Yes and no, I think the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has done a good job in creating interest at the European Union level in the challenges up here. On the other hand, in terms of concrete investments they are plainly not doing enough. In neighbouring Northwest-Russia, plans are being laid to build new roads and infrastructure to the tune of 100 billion NOK. On our side of the border, there is however nothing of that scale planned.

The latest news regarding the closed down fish-factory and the land surrounding it is that an investor-group from Southern Norway have been given an option to rent the area. In the glossy brochure they have produced they call the Vardø Barents Baset – Your closest point. They refer to the aerial distance from Vardø to Shtokman compared to that from Kirkenes and Hammerfest. The public face of the investor-group is Bjørn Dæhlie, the previous Norwegian ski-champion.

– What does Vardø town itself think of the plans for the Vardø Barents Base?

– Let us not forget that Shtokman is a Russian field, and that, thus far, no major oil or gas discoveries have been made in the Norwegian sector of this part of the Barents Sea. In terms of future jobs I still think that we have to concentrate on fish and tourism. People will always want food and enjoyment, says Rolf E. Mortensen, the mayor of Vardø.

– Anything oil and gas can bring us, we must therefore regard as a bonus, he continues at the same time explaining that Vardø has an excellent location for future operations in respect of high sea security and oil-protection: – The Norwegian Coastal Service is already located here, with a 24-hour Maritime Safety Watch station, following traffic at sea from Trondheim to the Russian border, and that ought to be a good start to build an environment for such knowledge, he underlines.

At the supermarket in Kirkenes the cashier is speaking Russian with the customer in front of me. Probably ten percent of the town's population are recent Russian immigrants. In many parts of Eastern-Finnmark large sections of the population are ancestors of the Finnish immigrants who arrived in the early part of the twentieth century. Elderly people in the area still speak Finnish with each other.

Almost one in five grown-ups in Finnmark is not in paid employment (see article on pp12-14). Do they constitute a potential labour force or not? – More no than yes I would say, answers Bernt-Aksel Larsen, head of East-Finnmark Regional Council. He is, to a large extent, reflecting the general opinion: – The point is that our settlements are very widespread. In Kirkenes there lack of labour, while here in Vadsø we have unemployment. The trouble is that there is some 200 km between the two towns. Secondly, since Kirkenes is at present experiencing a boom, housing has become very expensive. Thirdly, I guess it is also fair to say that most Finnmarkers are what you could call home-lovers.

Finnmark is a very thinly populated part of the world. The total area is 48 637 square kilometres, a little more than Denmark's 43 094. For Norway as whole the population has grown approximately 50 %, from 3.5 to 4.5 million over the last fifty years. Finnmark on the other hand reached its population zenith in the 1960s with around 78 000 inhabitants. Since then it has been declining and today has around 72 000 inhabitants. The largest populations in Finnmark are to be found in Alta (18000), Hammerfest (10000), Kirkenes (9500), Vadsø (6100), Honningsvåg (3250) and Vardø (2400).

– The three largest communities have at least managed to retain their populations but one should be aware that in recent years approximately 1000 Russians have settled in Kirkenes, and without them the population would have been 8500. Similarly here in Vadsø we include the 600 refugees living here on a temporary basis in our figures, explains Bernt-Aksel Larsen.

The recent immense surge in Chinese growth has seen global steel-prices rise to an all time high. For this reason there are now plans to reopen the iron-ore mines at Bjørnevatn, 12 km outside Kirkenes. 250 workers will be needed from the start:

– But we do not know where to find them and we will have to look both to Russia and to Finland. Russia in particular holds many possibilities. They are in the process of closing some minor mines on the other side of the border, says Oddgeir Danielsen, the Port Director of Kirkenes. – But there is one major obstacle, and that is that you still need visas to cross the border between the two countries, he adds

More than anything else he and many others involved in trade and industry in the county hope that the central authorities will ease border-crossings: – What we want to get is a special passport for people living in the border-area. With such a document crossings could be made much easier. You could drive to work in the morning and back in the evening.

In Norway, it has been official policy for decades to spread public jobs widely across the national territory. One outcome of this is that the tiny municipality of Vardø has 20 lawyers in its ranks. They all work in the State compensation office dealing with victims of violent crime. Similarly in Kirkenes the Norwegian National Collection Agency has a section employing 200 public officers. Modern technology facilitates further expansions in this direction.

By Odd Iglebaek