St. Petersburg (above) is the largest metropolitan area of the Baltic Sea Region.

Photo: Merete Bendiksen/norden.org

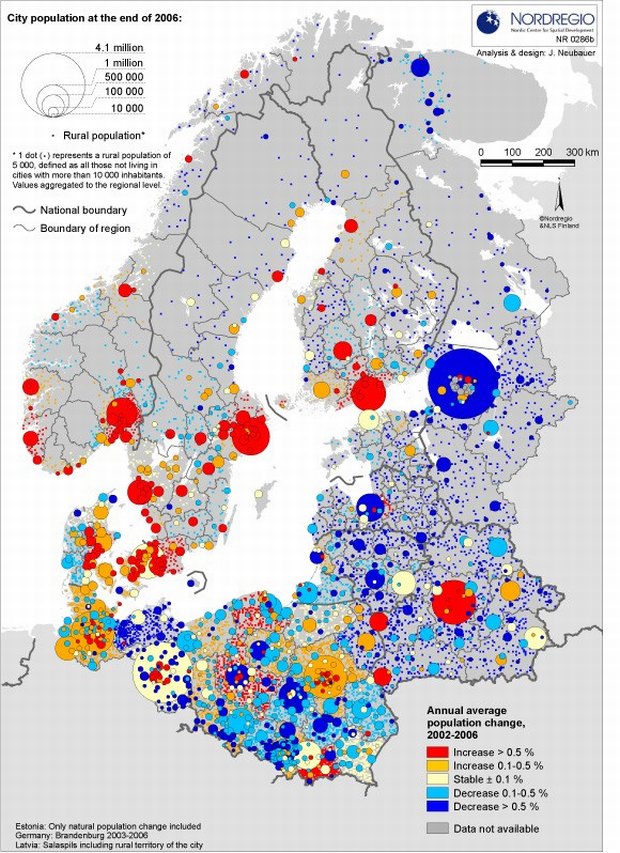

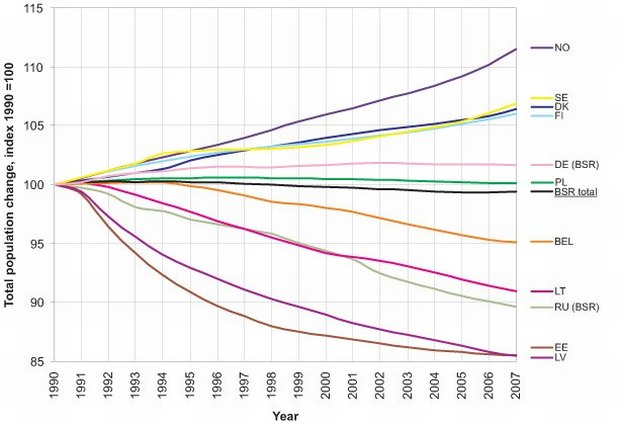

Indeed the entire BSR shows only a slight decline in total population (see chart p. 23), but on closer inspection we see that continuing overall urban growth goes hand in hand with rural decline, although with contrasting tendencies between the various countries involved.

More specifically, we can observe a spatial polarisation of population towards capital areas, larger agglomerations and higher order urban centres across most of the BSR, which is followed by accelerating suburbanisation in and around the main metropolitan areas.

Additionally, numerous small and medium-sized cities and towns on the fringes of the capital areas and other urban agglomerations can be seen as the winners because, in the 2002-2006 period, they saw the most rapid population expansion of all mainly due to significant in-migration flows (see map p. 22).

The majority of small and medium-sized cities and towns, and specifically those that are to be found in relatively peripheral situations, are however increasingly hampered by shrinking processes. This means that the disparities between cities in terms of population have widened recently as compared to an earlier study by Hanell and Neubauer (2005) for the 1995-2001 period.

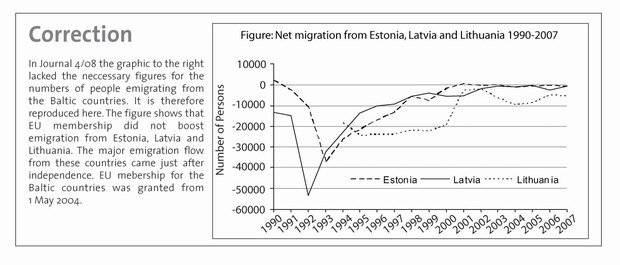

In other words, the key drivers of population change remain in place: strong migration surpluses in the Western part of the BSR and extensive natural losses in the Eastern BSR, with, however, distinctive national and regional variations pertaining.

What is even more alarming however is the fact that these contrasts, specifically between most of the Nordic cities and most of those located in the Baltic States, NW Russia, and Belarus and to a lesser extent in Poland and North East Germany also, will grow at an ever increasing velocity.

According to the latest national forecasts in the BSR one can anticipate – with the exception of the core regions in the Nordic countries – a general decrease in the overall population which goes hand in hand with the 'emptying' of rather peripheral areas and those that are characterised by somewhat isolated small and medium-sized cities and towns and their rural hinterlands.

Stable developments are for the most part to be expected in the larger metropolitan areas (here often at their fringes rather than in the cores) – some will even increase in population such as in the Nordic countries.

The basic driving force of these trends and their territorial impacts is the relatively low birth rate in many BSR-countries, which can be compensated for in only a few regions by in-migration. Additionally, on the other hand, many cities and regions will be even more hampered by out-migration in the near future, not necessarily just to other BSR-countries, but to the rest of Europe more generally.

In consequence, many cities and regions, specifically in the eastern and southern part of the BSR will increasingly suffer from a shrinking labour force (i.e. less people of working age) as well as from a greying population (i.e. more people of pensionable age).

Taking into consideration the labour market or the regional GDP per capita we see also sharp contrasts between several BSR cities and regions. One can thus say that, on the one hand, the overall picture in respect of the traditional East-West divide remains. On the other hand however we can observe an ongoing differentiation, i.e. the mosaic of well- and less-well performing cities and regions and those which are increasingly catching-up is becoming wider and ever more diverse.

Naturally, this differentiation can be interpreted as a kind of normalisation process with regard to the larger cities and metropolitan areas in the BSR as they are simply following trends found elsewhere in Europe. Nevertheless, due to the spatial structure of the BSR, which – compared to the rest of Europe – is peculiarly impeded by a number of specific circumstances (such as long distances, isolated border-regions, sub-arctic climate, sparsely populated regions), the BSR needs to formulate a different approach (as compared to other European macro-regions) towards territorial cohesion.

In view of the long-term sustainability of the BSR, the shrinking labour force and the safeguarding of public infrastruc-tures, combined with the retention of an acceptable level of public service provision 'greying societies' will remain among the most persistent challenges up to the year 2030 and most likely even beyond.

In addition the ongoing emptying of rural areas demands the adoption of new strategies in respect of how to use existing cultural and natural resources in the future. Alternative paths will have to be defined for such areas including the development and promotion of 'soft' tourism, recreation or nature conservation.

To enhance the birth rate in most BSR countries and thus to contribute to the stable and sustainable reproduction of the BSR's population is not necessarily only a national concern.

Local and regional services can contribute enormously by supporting the ability of families to better combine family and work/education in their everyday lives.

Further Reading:

Schmitt, P./Dubois, A. (2008): Exploring the Baltic Sea Region – On territorial capital and spatial integration. (Nordregio Report 2008:3), Stockholm, 138 pp.

Hanell, T./Neubauer, J. (2005): Cities of the Baltic Sea Region – Development Trends at the Turn of the Millennium. (Nordregio Report 2005:1), Stockholm, 128 pp.

By Jörg Neubauer, previous Research Fellow at Nordregio, now Swedish Energy Agency, Executive Officer, Planning Department – Wind Energy Unit and Peter Schmitt, Senior Research Fellow.