The Øresund-brigde for both vehichles and trains (below) is an important link in the TNT-network.

Photo: Johannes Jansson/norden.org

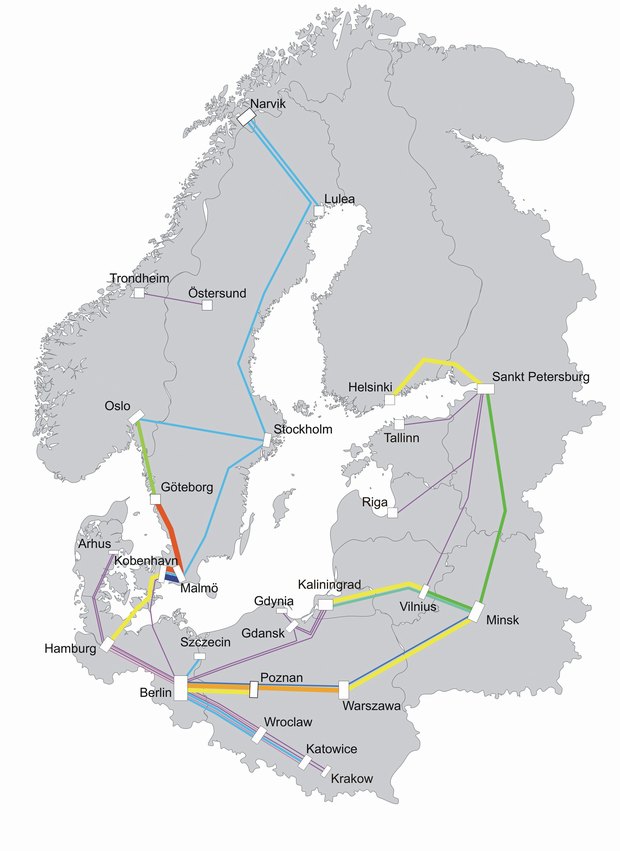

Moreover, while Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius remain inadequately connected to each other, they all do have direct connections to St. Petersburg, even if the frequency of these routes is rather low (6 weekly direct trains each). In this regard, Minsk appears to be central here in acting as the connection hub between North West Russia, Kaliningrad and Poland in addition to Belarus itself. Indeed, Minsk boasts not only direct rail connections to Warsaw, Vilnius, Kaliningrad, but is also a necessary way-station for mobility between these cities.

The integration of the transport networks of the countries composing the BSR has been perceived, since the emergence of the macro-region in the beginning of 1990s, as a condition sine qua non for improving the integration of its regional and national economies. Consequently, it is not surprising that this specific theme has been central to the work of the Visions and Strategies Around the Baltic Sea (VASAB) organisation, since the adoption of its first 'vision' in 1992.

The Gdansk Declaration, the latest document adopted by VASAB, again highlights the importance of the role of transport infrastructure in enabling connectivity between regions within the BSR but also beyond it, emphasizing in particular the need to adapt these infrastructures, as well as logistic chains, to the territorial diversity of the macro-region.

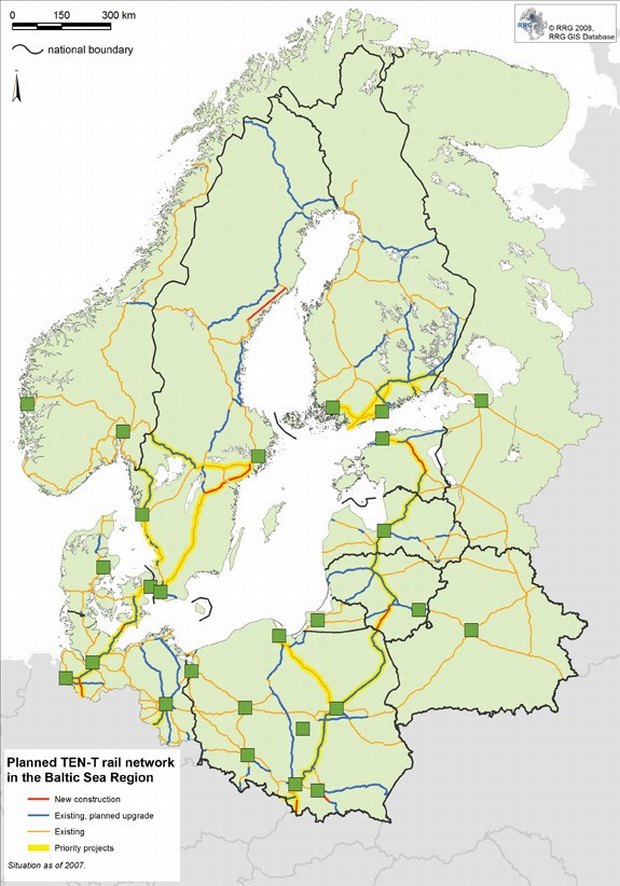

More importantly, the document stresses the importance of EU policies with regard to accessibility issues. Improved accessibility is seen as an important part of the Community Cohesion Policy, and the planned investments in the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T and TINA) are seen as crucial in improving the connectivity of the BSR to the rest of the European continent. The development of the Transnational European Networks represents a key part of the EU's strategy to achieve an integrated Internal Market, and is also a key vehicle in furthering EU – Russia integration.

The most emblematic and probably also the most problematic challenge in this regard corresponds to the lack of inter-operability of the various national railway networks, due to differing technical solutions and their varying degree of technical sophistication. This remains a limiting factor in the quest to facilitate the mobility of persons and goods across the border, particularly on the Eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, from Poland to North-West Russia.

As for the differing technical solutions, the main challenges remain the differences in gauge-size between the Russian (1520mm) and European (1435mm) systems. In addition to Russia, Belarus and the Baltic States have also inherited the Russian gauge standard, due to their inclusion in the former Russian Empire, and consolidated during the Soviet era. Finland also has the Russian gauge system for similar reason.

In Poland and Kaliningrad, both systems can be found due to the area´s later inclusion in the "Russian sphere": Kaliningrad was previously part of Germany before being annexed to the Soviet Union, while the territories of Poland was split between Russia and Germany/Austria during the 19th century.

Consequently, these territories become central interfaces in enabling the integration of both railway system types on the Eastern shore of the BSR.

The integration of the Eastern BSR railway networks is important on two main levels: first, to connect the main metropolitan areas (Warsaw, Vilnius, Kaunas, Riga, Tallinn and Saint Petersburg) and second, to act as an interface between 'continental Europe' and Russia.

The lack of North-South linkages in the Eastern BSR can be seen, in the main, to relate to the historical heritage of the region and to the 'divide and rule' Empire-building approach of the former Soviet Union: East-West linkages, connecting each Soviet republic to the central powerhouse of Moscow, were developed and inter-regional linkages very consciously avoided.

On the Eastern shore of the BSR, this results in a persisting lack of reliable, modern infrastructure, for instance double and electrified tracks, connecting the main cities.

These 'missing links' are well highlighted by visualising the frequency of transnational (i.e. crossing a national border) rail services between the BSR's main metropolitan areas (See figure 1).

Indeed, the figure clearly shows the still poor level of connectivity of the main metropolitan areas on the Eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, i.e. between Poland, the Baltic States, Western Russia and Belarus.

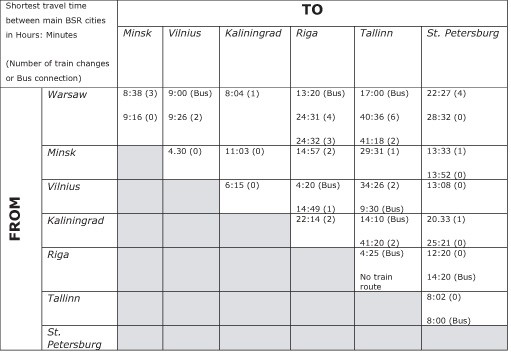

Table 1 provides further indications of the implications of the poor connectivity of the rail system on the Eastern shore of the BSR by assessing the time that it takes to travel between these cities.

The poor quality of the rail infrastructure in this part of the BSR and the lack of cross-border interoperability in respect of the existing track networks not only ensures longer travel times, but also necessitates a significant level of inconvenience for the traveller as multiple changes are often needed along these journeys. Currently travelling from Warsaw to Tallinn takes 40 hours and 6 changes to complete the journey.

The main problem related to rail infrastructure is witnessed between Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. For the journeys between capital regions, bus connections are often faster, as, for instance, between Warsaw and Vilnius. There is still, to date, no train connection between Tallinn and Riga.

In an earlier report commissioned by VASAB (Nordregio et al., 2000), it was noted that no train connection was available between these two cities in 1999: nearly a decade on the situation remains the same.

The second main dimension promoting the necessity for further integration of the railway networks on the Eastern shore of the BSR lies in its trans-continental nature. Indeed, the geographical position of the BSR reveals its role as a potential 'natural' hub, acting as an interface between Europe and Asia. In this regard, Saint Petersburg is a key centre as it facilitates connections between the BSR and the greater Russian railway system and thus also to the countries of Central and East Asia.

This trans-continental potential is further enhanced by the importance of the Tallinn-Saint Petersburg railway corridor, to date the busiest section for freight transportation in Europe (Schmitt & Dubois, 2008).

In addition, the importance of Warsaw as a hub between the BSR railway system and the 'continental' European one (See figure 1), not only because of its relative territorial location in the BSR but also because it is connected to both gauge standards, reinforces the need to support an upgrading of the networks between Warsaw and Saint Petersburg in order to better facilitate such trans-continental linkages.

The further integration of the railway systems on the eastern shore of the BSR has repercussions not only for the capacity to integrate further its regional economies and labour markets, but also in terms of the capacity of the BSR to act as a global player, acting as an interface region between Europe and Asia.

Yet, the persistence of structural deficiencies endangers the achievement of this potential. In this light, the completion of the TEN-T Rail Baltica project (See figure 2), running from Warsaw to Tallinn, needs to be recognised as a high priority project by the European Commission and the governments of the BSR countries.

Furthermore, it quickly becomes clear that the completion of the Rail Baltica project should be connected to future plans for the upgrading of the Tallinn-Saint Petersburg section of the network, which would ensure a good connection between the TEN-T and Russian networks.

More than an upgrade in reality, it is in fact only a complete renewal of the section of track to the European standard (1435mm), thus replacing the current Russian one (1535mm), that will ensure the future integration of Russia within a predominantly EU/EEA BSR region.

Figure 1: Route frequency on main cross-border rail connections in 2008 (weekly)

Source: Deutsche Bahn (2008), RRG Spatial Planning Database

Planned TEN-T tail network in the Baltic Sea Region.

Table 1: Shortest travel times between main cities on the eastern shore of the BSR

Source: Deutsche Bahn (2008), Eurolines (2008)

The author would like to thank Carsten Schürmann (RRG Spatial Planning) and José Sterling (Nordregio) for their support for the compilation of the empirical data shown in the present article.