In such a specific 'territorial' perspective cities, and in particular so-called metropolitan areas, can be seen as promising nodes of complex transactions in respect of economic activities, informa-tion, power, culture, and finally people with their specific knowledge and skills. In this sense they can be viewed as the main drivers of (transnational) spatial integra-tion. So in this context the concept of spatial integration is linked to the actual (or potential) performance of territorial linkages at a larger geographic scale.

Spatial integration is then supported by specialised networks of e.g. cities as defined by common patterns of either material or non-material production. Trade and any other kinds of transactions (e.g. knowledge, labour forces, cultural heritage and institutional traditions) are based on complementarity, cooperation and finally, on trust.

As such, spatial integration could be understood as the sum of interactions among cities in a network, making them the drivers in a dynamic polycentric organisation. Moreover, these potential (or wishful) synergies and add-on effects can have positively influence an entire transna-tional macro-region, such as the BSR.

Nordregio´s recently finalised study in the framework of the Interreg

IIIB-project East-West Window has revealed that the metropolitan areas in the BSR show some significant differences in terms of quantity but also, partly, in quality with regard to their functions as potential internationalised drivers for spatial integration: Not surprisingly the transformation into global and European markets is apparently a long-term process. On closer inspection a number of promising potentials seen as critical in supporting the process of spatial integration can also be identified.

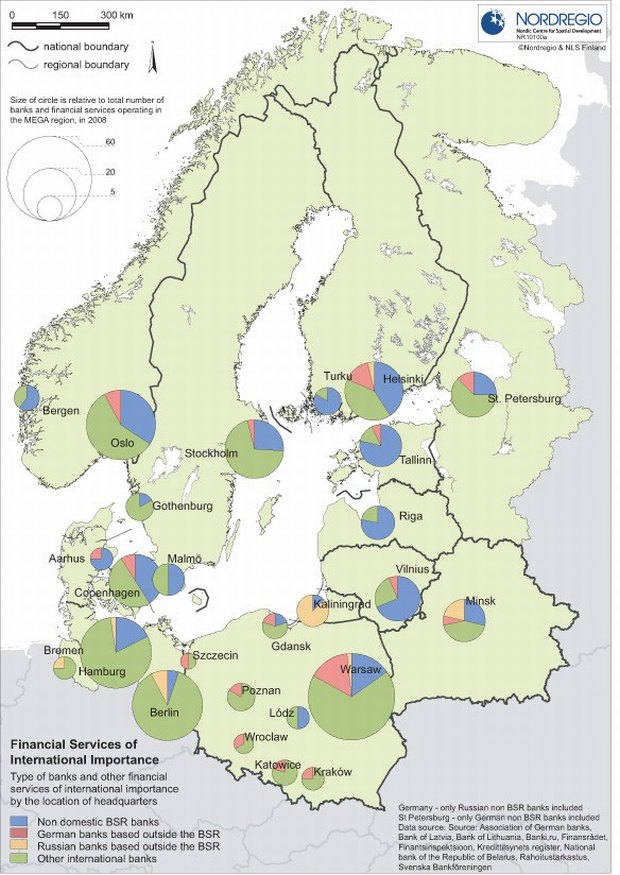

International Financial Services

The study also indicates that interna-tional financial services have not thus far established a strong and cohesive network in the BSR particularly in respect of connecting the NW Russian metro-politan areas to the rest of the BSR. One exception here is obviously that of Warsaw, which has, in many respects, caught up with some of its Western BSR counterparts such as Stockholm or Copenhagen. It is to be questioned, how-ever, why international banks have not established office locations in Kalinin-grad, Minsk or St. Petersburg.

This is, however, a huge and complicated subject. The issue boils down to (1) legal issues, (2) market dominance by Russian state run institutions and (3) the fact that profit opportunities in Russia – compared to elsewhere – are still seen from the outside as both risky and limited.

Due to the potentially enormous market size of the Eastern part of the BSR and the (in principal) growing markets there, such an absence could be seen to impede inward investment. The current lack of such services can however be interpreted as an institutional barrier to the further exploitation of the potentially enormous market size of the Eastern part of the BSR and the fast growing markets there (cf. adjacent map).

This also includes additional services for international companies in order to ease their engagement into the BSR in general and its Eastern part in particular as such services are vitally important in develop-ing a more balanced situation in respect of institutional, social and cultural proximity. The current 'credit crunch', which has seen a significant amount of capital 'repatriated' from Eastern Europe, even to the extent that some countries in the region have opened discussions with the IMF, has simply exacerbated the prevailing situation further.

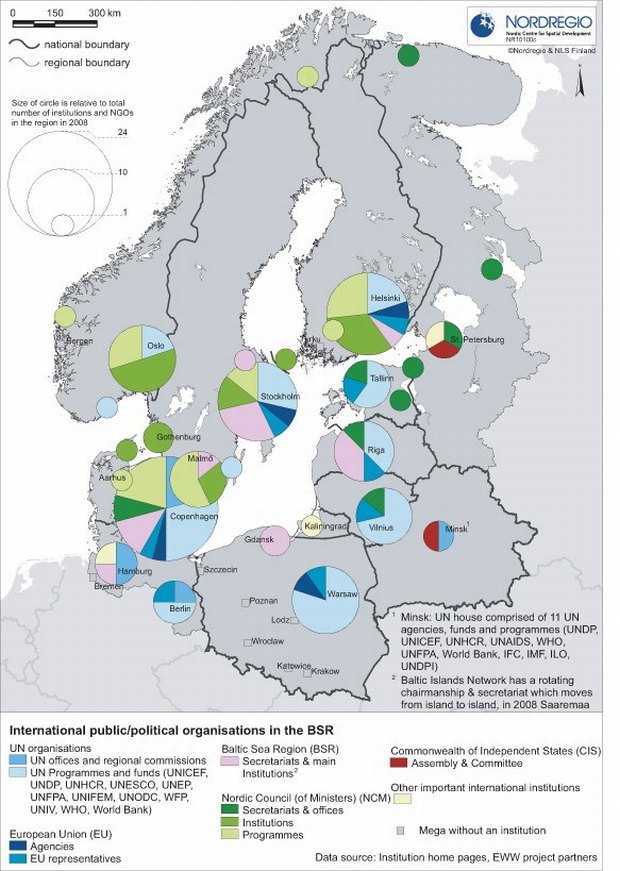

International Political Institutions

The analysis of the character of the location pattern of international political institutions further underlines this picture: At the BSR level neither Kaliningrad nor St. Petersburg are major spatial integration drivers. They are obviously more oriented towards their eastern hinterland giving the impression that the geo-political, institutional and psychological barriers remain in place.

Overcoming these barriers remains a long term and complex process which goes far beyond the spatial policy realm. Otherwise BSR-related political insti-tutions are particularly located in Copen-hagen, Stockholm, and Riga and to a lesser extent in Hamburg and Helsinki while EU-related institutions are present specifically in the three Nordic capital regions (Copenhagen, Stockholm and Helsinki) and in Warsaw.

Warsaw also seems to be the most important centre in respect of UN-related institutions in the BSR. In conclusion then, it is clear that the metropolitan area of Copenhagen contains the broadest representation of such international organisations while also having the most diversified profile in this respect (cf. adjacent map).

Potential Talents

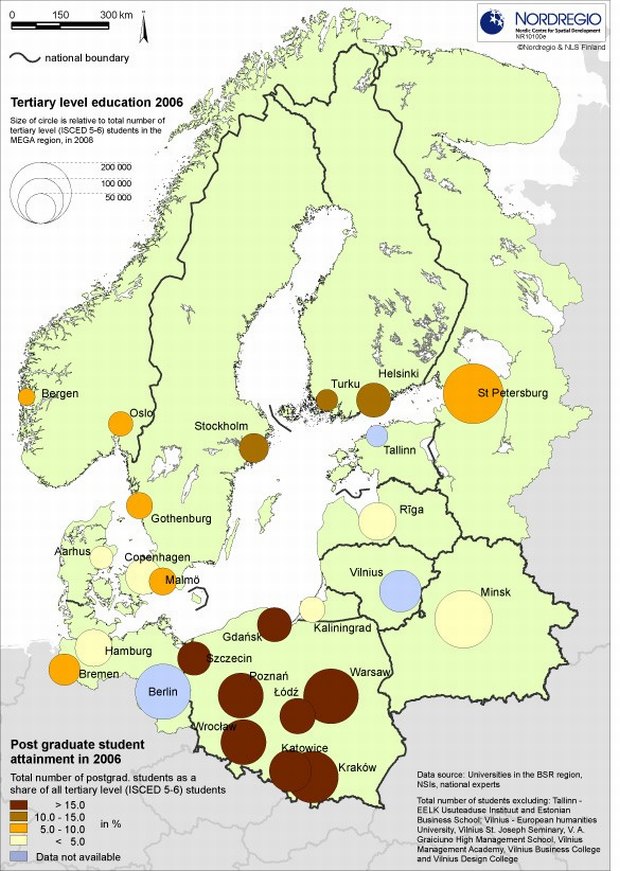

Concerning the analysed indicators on innovation, research and development we can conclude that the East-West divide is somewhat narrower than the illustrated examples above. Here numerous compe-tences and significant potentials exist given the high critical mass of talented and creative employees and the strong research profiles across the BSR.

This particularly relates to the number of postgraduate students ( Masters or PhD students) as a share of all tertiary level students belonging to levels 5 and 6 of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) designed by the UNESCO (see map p.28).

What is striking however is the number and share of those students (related to all tertiary levels) in the Polish metropolitan areas. Obviously there are a number of attractive research facilities here which are able to hold or even attract qualified persons.

Other eye-catching centres in the BSR include St. Petersburg and Stockholm, whereas the Finnish metropolitan areas of Turku and Helsinki show lower overall numbers, but a high share of post-graduate students as a proportion of all tertiary level students.

Compared to their overall size as working places the absolute numbers of Warsaw in particular but also Minsk, Vilnius and to some extent even Riga are relatively high, whereas the overall numbers for Ham-burg, Copenhagen and Oslo are rather low in this respect.

Intellectual property rights

With regard to the degree of internat-ionalisation one specific indicator was considered here, namely 'applications of patents to the European Patent Office'. The level of performance, in terms of the 'ambition' to secure intellectual property rights for European markets, of the Eastern BSR metropolitan areas remains, however, rather weak. It is not necessarily the shortcomings in respect of the regional innovation systems (e.g. infra-structure, R&D expenditures) which have to be stressed here but rather institutional and perhaps also cultural traditions, which in the long run often perpetuate the disconnectedness of e.g. the Baltic States with the rest of the BSR.

Gateways

We also considered several classical transport aspects with regard to the international functioning as 'gateways to markets and people' of more than a dozen metropolitan areas around the Baltic Sea. Their performance is in this respect dependent on the size, the capacity and the actual services that are carried out by the available infrastructures (cf. the contribution by Alexandre Dubois in this issue). Here significant contrasts could be detected while numerous bottlenecks remain to hamper the smooth flow of people and goods within the BSR and beyond.

We should, however, also bear in mind that current air transport patterns are historically rooted and remain dependent on the long term strategies of airlines and of course their commercial viability in the highly competitive market for air transport. Current patterns in respect of sea transport, roads and rail have also been developed over a number of decades. As such, complete integration and the removal of all bottlenecks would be hugely expensive and is thus highly unlikely in the medium term. Nevertheless, when taking into account the prevailing settlement patterns and regional structures in the BSR, we should also bear in mind that proposing additional and highly costly large-scale infrastructures in order to balance these disparities could lead to a ruinous competition and, from a purely BSR perspective, to the playing out of a zero-sum game.

Going beyond geographic proximity

We can therefore conclude that political stakeholders have to understand that if the balanced and sustainable spatial integration of the BSR is to be achieved, the metropolitan areas themselves must play a key role.

Their specific international functions should be enhanced in order to support the flow of people, ideas, projects and knowledge as well as their financial capital and the goods and services they produce. These functions and potentials as well as the urgent problems faced have to be better understood at the political level and disseminated beyond that in order to ensure that such knowledge becomes the stock of an effective shared store of transnational understanding. As such then new Pan-Baltic concepts are needed to better position the BSR's metropolitan areas in terms of the ongoing international competition for 'creative people', investment, first-class infrastructure programmes and events.

Without doubt thinking about the need to better exploit the region's territorial capital as well as improving the degree of spatial integration, challenges both our perceptions as well as many of our policy-making assumptions.

Central to this, however, is the fact that not only is investment in physical infrastruc-ture projects to improve the geographic proximity of the many cities and regions needed but rather more importantly perhaps, institutional, organisational and mental proximity related questions must also be addressed.

As the examples here have indicated the need remains for reliable business trans-actions thus necessitating the creation of corresponding institutionalised frame-works. Indeed, it appears that the creation of these frameworks is at least as important as the need to overcome the problems associated with distance. Only then can the BSR's territorial capital be fully exploited.

VASAB

VASAB is an intergovernmental network of 11 countries of the Baltic Sea Region and other pan-Baltic organisations promoting cooperation on spatial planning and the development. Its role is to pinpoint the enormous potentials with regard to further spatial integration, while at the same time promoting improvements in the institutional, and organisational structure of the region and in its mental proximity.

Due to the fact that spatial planning (and the responsible ministries in the BSR) in general, and the mandate of VASAB in particular, is integrationary or coordination-based in nature, their tool box is thus rather limited as regards their ability to actually implement concrete incentives. Therefore they need to establish strategic alliances with those policy-makers dealing with sectoral issues (e.g. higher education, research, transport, ICT, energy etc). Only with their support and their sound financial backing can such strategically integrative concepts as the Long-Term Perspective (and perhaps also the EU Baltic Sea Strategy) become more than another paper tiger.

Maps by Johanna Roto