The new Alcoa Fjaardal aluminium smelter in Reidarfjördur is planned to start full production by 2008. Here on a cold May-day 2007. Photo: Odd Iglebaek

It is almost the middle of May. The weather is grey and there is a flurry of snow in the air. In Reidarfjördur the administrative centre of the municipality of Fjardabyggd it is however nice and warn inside the new shopping mall. The offices of the administration are located on the floor above. So notwithstanding the winter-storms, you only need to go down one flight of steps to get your daily dose of fresh fruit or vegetables. Considering that everything is imported, and the market is so small, it is fascinating to note that the selection and quality of produce available is as good as that in many of the high-street super-markets in Europe's capitals. Prices are not all that much high either.

A bit further along the fjord the new aluminium smelter is under construction. Two approximately 1 km long production halls are sited in parallel to the shore. Hundreds of people from all over the world, though most are Poles, work full shifts here to get the job done. It is the US-based company Bechtel that is in charge of construction. They also arrange for the necessary labour. – Everything is going more or less according to plan and we have had no major accidents, says Hilmar Sigurbjornsson, PR-officer of Alcoa Fjaardal, the actual name of the production plant. – And if everything continues to go well, the new smelter will be able to run at full capacity with a yearly production of 364 000 tonnes of aluminium by the summer of 2008, he adds.

Fjardabyggd has approximately 6000 inhabitants plus 1600 guest-workers. – This has not however created any problems whatsoever, underlines Helga Jónsdóttir. There are weekly flights directly from neighbouring Egilstadir to Warsaw. In fact some of the permanent citizens in the municipality also come from Poland. They originally settled in Iceland to work like so many others in the fishing-industry. In total there are currently some 18 000 foreigners living in Iceland. Their share of the population has grown from around 2% in the past to a current high of some 6%. Less than one third of these foreigners however work in the construction industry. The majority are to be found in the health sector, hotel and catering and cleaning-companies.

A few years ago Fjardabyggd consisted of four separate municipalities, one in each fjord:

– Now we are building tunnels like the Norwegians, and soon we will all be within driving distance of each other, explains Helga Jónsdóttir.– But maybe the best thing is that people are no longer at the mercy of local 'chiefs' for jobs. Now people can find work outside 'their' fjord and still return to their families in the evening, without having to negotiate with the lords of the fisheries, she explains.

The new aluminium smelter in Reidarfjördur will need a staff of 400 when it is up and running: – Thus far some 230, mostly local people, have signed on, but I do not think it will be a problem to attract the rest. What however could be a problem is the cost of housing. Prices has gone up by 20-30% in just a couple of years and will soon reach the levels of Reykjavik, explains Helga Jónsdóttir. She also reckons that there will be a need for another 400 new jobs in her community in addition to the 400 in Alcoa Fjaardal: – And that means a greater likelihood of attracting schools and services, so it is definitely an exiting time to be here, she adds mentioning that she has previously worked both in Reykjavik and with the World Bank in Washington DC.

The neighbouring municipality is Fljótsdalshérad. It consists of the town Egilstadir with some 2600 inhabitants and a hinterland with an additional 800 inhabitants. Even though it is small, it is in many ways the capital of Eastern Iceland. It has an airport with several daily flights to Reykajavik. The flights take one hour compared to the 10-12 or more it takes to drive. The distance is much the same, some 620 km, whether you take the northern or the southern route, and the road surface can be quite rudimentary in places. In Egilstadir however it is prosperity that rules; the town has two good restaurants and a small golf course and has long been a hub for rich international salmon-fisheries. Mayor Eirikur Bj. Björgvinsson, however, underlines that there are social problems here, and that he appreciates that the new economy provides better opportunities to solve them than was previously the case.

Some 600-700 metres above sea-level, on a windswept mountain plateau, there are complex housing several hundred construction workers. Many of them come from China, others from Malaysia, Italy or Poland. They are all here to finalize construction of the dams and tunnels for the new hydro-power station named Kárahnjúkar. The main building-company is Italian Impregido.

The man who flies in to check on the installation of transformers in the huge 35 meter high mountain cave called the turbine-and generator hall has a wife and a young son at home, that is just outside New Delhi. His name is Rakesh Chakraborty and he works for the French, or was it Swiss, company Areva. Rakesh's last job was in Morocco.

Definitively then an international community exists up here in the mountains, with, at present, some 1800 workers involved in the construction process. From late next year and onwards however it will dwindle to 20 on a permanent basis. That is the staffing needed to run the new power station.

Karahnjukar is expected to cost a total of 1.2 billion US-dollars, while the new Fjardaal aluminium smelter in Reydafjordur, which it will serve with electricity, is of the same scale, i.e.1.3 billion US-dollars. There are many differences between the two projects. One such difference it that while there have been no major accidents during the construction process in Reydafjordur; four lives were lost during construction at Karahnjukar. That is the sad part of the Klondike-story in Eastern Iceland. It should also be noted that it was representatives from Landsvirkjun, the owner of Karahnjukar who provided this information. They also mentioned that all four worked for Icelandic companies.

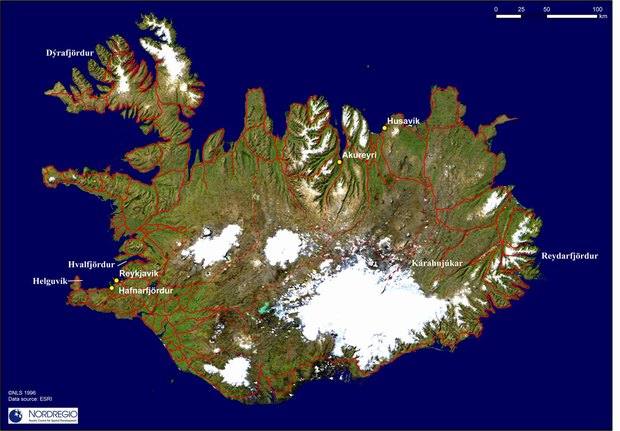

There are more communities in Iceland interested in aluminium planters and waiting for similar industries to arrive. First in line is Husavik up north and Helguvik near Keflavik. In Drafjördur, to the far north-west, 'private interests' have started to talk about an oil-refinery, wich, if not based on Icelandic oil then possibly on imports from Russia, this could potentially signal another 'Klondike experience'.

By Odd Iglebaek