Iceland's local authorities' share of public spending is relatively small while the State takes responsibility for many of the costly functions handled by local or regional authorities in other Nordic countries. The larger role played by the central government in Iceland can be attributed to the size and disparate territorial distribution of the population. The degree of centralisation and concentration to the capital, Reykjavik, is also a major factor here.

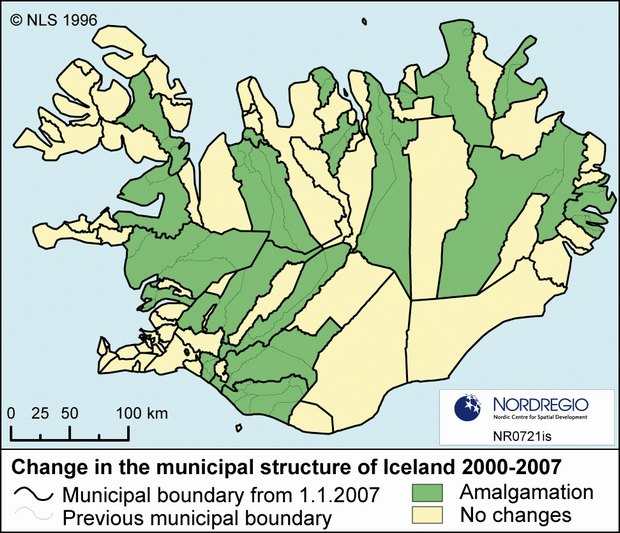

The differences between municipalities are considerable, with geographical size ranging from 2 to 8 884 km2 and population from 38 to 113 730. The number of municipalities had decreased from 124 in 2000 to 79 at the time of the local elections in 2006.

This decrease in numbers is even more marked when viewed within the wider context of Iceland's municipal history: at its highpoint in the 1950s there were a total of 229 municipalities on the island. The major share of the municipalities' work continues to entail the management of primary education.

The fragmented local authority structure has however also led to municipalities joining forces voluntarily, in order to deal with particular service-provision needs, such as care for the elderly, waste management, and co-operation in the fields of culture, sport and public transport (where applicable, i.e. in the capital area and in Akrueyri and Isafjordur).

Roads and transport are areas where inter-municipal collaboration is the norm, and where regional plans have already been drafted as stipulated by the Planning and Building Act No. 73 from 1997. Additionally inter-municipal co-operation already takes place in respect of some social service provision.

Public debate has reflected a range of similar concerns to those emerging from the Danish structural reform process, i.e. restructuring local authorities to make them strong enough to adopt new responsibilities. Increased decentralisation has, in part, been supported in order to render clearer the division of tasks between central and local government.

The increase in the local level share of public consumption also remains a significant goal. The services that have been considered suitable for decentralisation have therefore included issues that in many cases come under the ambit of 'local level responsibility' in the other Nordic countries, e.g. basic healthcare services or care for the elderly. While healthcare is not really discussed as a candidate for restructuring in terms of the redistribution of responsibilities, a measure of debate has occurred, and plans to transfer care for the elderly to the municipalities have been drawn up.

The 2005 referenda on municipal mergers did not achieve the kind of mandate hoped for by those proposing further mergers. Instead of the 16 mergers proposed, the referendum resulted in only one amalgamation taking place. The process was subsequently put 'on ice' either to be revisited in the future in the context of a more 'top-down' style amalgamation process, or as a variation of the Finnish and Danish processes, i.e. 'voluntary' mergers or forced co-operation (leading gradually, it is hoped, to mergers as co-operative ties and where functional interdependence can be strengthened). This issue has however been somewhat superseded by national issues in the context of the general election campaign of May 2007.

The victory margin of the sitting governing coalition (the Independence Party and the Progressive Party) in the May elections was extremely narrow. The Independence party and the opposition Social Democrats subsequently however decided to form a new majority government with 43 of the 63 seats in the Parliament. This also means that the municipal question will now probably re-emerge in the near future. If the previous Social Democratic position on this matter, i.e. supporting a minimum size of 1000 inhabitants per municipality is anything to go by, changes are likely to occur.

By Kaisa Lähteenmäki-Smith, previous Senior Research Fellow at Nordregio