Iceland has currently a high number of temporary workers particularly in the construction industries. Photo: Odd Iglebaek at Kárahnjúkar

Furthermore, the economic gain from a presumptive highly-skilled immigrant must be relatively higher for choosing a Nordic country relative to other countries (e.g. the USA, the U.K. or Germany). A structural change in the economy must be promoted, not obstructed. This, however, is likely to remain a difficult political proposition unless Nordic voters more generally are willing to support change. The longer we wait, the more valuable time will be lost in attracting 'good' immigrants.

After the recent EU-enlargements of 2004-07 the volume of labour migrants has not been as large as expected to the Nordic countries. The growth rate for labour migration, since 2004, has nevertheless increased particularly for Norway and Iceland, while labour migration to Sweden and Finland continues to stagnate. The volume of labour migrants to the Nordic countries nevertheless remains relatively small.

Ongoing structural changes in the economies of the Nordic countries have culminated in a process of de-industrialisation. The new 'knowledge-driven' service economies in the Nordic regions thus now need highly educated labour, while the immigrants entering the Nordic labour markets are, generally, low-skilled labourers.

From where will new labour migrants come?

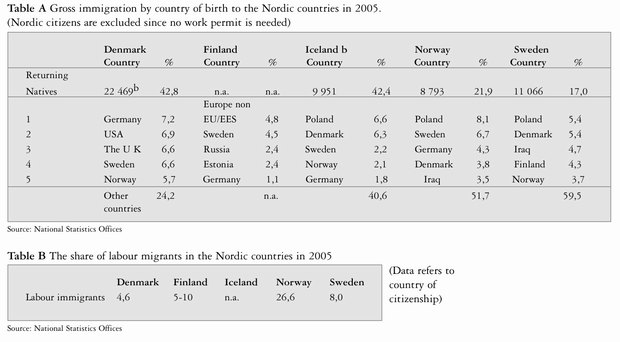

In all Nordic countries labour migrants from the new (post-2004) EU members constitute a minority of all labour migrants; the majority of labour migration to the Nordic countries come from other Nordic countries, the 'old' EU/EES countries and from outside the EU/EES. Table A below lists the five major 'sender-countries'. Most immigrants to the Nordic countries are however Nordic nationals returning to their home country.

There are three major regions in the world where significant population growth will occur in the coming 50 years, namely, India, Western Asia and North Africa. Of all the countries listed in table A, only Iraq is situated in such a region.

Motives for migration

There are several motives for migration. Getting a job, becoming a refugee, getting married or family reunion, adoption, and studies are the most common motives. Over the last decade, lifestyle migrants have also become more common.

Only a small part of the total volume of immigration to the Nordic countries is related to labour immigration; e.g. 4.6 per cent in Denmark and 8.0 per cent of all immigrants to Sweden were labour immigrants in 2005.

It is clear that labour migrants want to work and they want to make money. Beautiful wildernesses, less pollution or sparsely populated regions do not attract labour migrants, though such things are of interest to lifestyle migrants.

Where do they work?

Agriculture and forestry are sectors which attract a relatively large share of labour migrants, as do construction and the labour-intensive manufacturing sector. Service jobs in the industrial cleaning, hotel and catering and transport sectors have also attracted many labour migrants. Many low-skilled immigrants moreover continue to pick up employment in "3D"-jobs (dirty, dangerous, and degrading). The share of seasonal and temporary work is also high.

Are these patterns new? The little information available indicates that, in the early 1970s, most intra-Nordic migrants had been engaged in unskilled manual labour before emigrating, and that such people generally also had a relatively low educational status. The share of unemployed among these emigrants was higher than the share of unemployed in the total population. When they arrived at their country of destination they usually picked up jobs in the labour intensive manufacturing industry, the construction sector, or in the hotel and catering sector, namely, in "3D"-jobs natives did not want to take.

A segmented labour market?

According to segmented labour market theory immigrants are willing to do the "3D"-jobs at wages no natives would accept. Immigrants will become a complementary work force in labour intensive manufacturing or in the lower segment of the person-oriented service sector. Thus, the wage structure for native labour will not be affected – immigrants do not take up those kinds of jobs.

Ongoing structural change in the economy has however resulted in immigrants following the vacancies available in the lower labour market segment. In consequence, labour immigration obstructs structural change in the economy as stagnant trades and sectors are kept going due to the continuing availability of cheap migrant labour. This will undoubtedly slow economic growth.

How to attratct "good" immigrants?

In the Nordic countries highly skilled immigrants are needed mostly beyond the metropolitan areas. If we are to assume that labour migrants are predominantly attracted by the prospect of attaining work we must be prepared to pay competitive wages relative to other possible destination areas to make it profitable for them to chose a Nordic country in which to relocate. Such economic incentives are the most effective tools for shaping desired outcomes. So, if the greatest need for labour is in the rural and peripheral parts of the Nordic countries, wages must be offered to make it attractive for labour to choose these areas. This may not only attract immigrants, in addition, natives may also begin to return.

Despite the demand for highly skilled labour, most vacancies open to immigrants are in the "3D"-job sector. This, in combination with a compressed wage structure, high taxes and an undercurrent of xenophobia, often sees highly-skilled migrants choose other countries. The perceived 'language barrier' and the often cold climate do little to improve this situation.

Attracting 'good' immigrants probably requires significant changes in the economic structures of the Nordic countries, in particular the breaking down of the segmented labour market. Though this will not be a simple task. As such, the abandonment of the 'Nordic ideal' of a compressed wage structure and high taxes -politically highly controversial – may therefore be necessary. As the new and the old societal structures continue to clash across the Nordic countries the increasing levels of perceived xenophobia generated by this basic uncertainty over what the future holds will however continue to ensure that 'good' immigrants chose other countries. The longer we wait before we start tackling these problems, the longer it will take to begin to attract 'good' immigrants.

By Daniel Rauhut, previous Senior Research Fellow at Nordregio