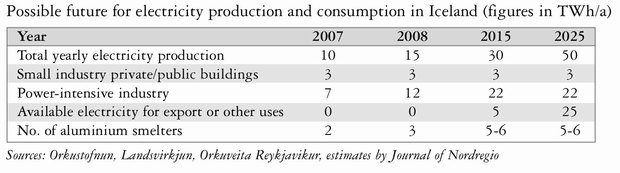

Iceland's production of electricity last year amounted to 10 TWh having almost doubled in just 10 years. Next year it will be closer to 15 TWh. According to official estimates there is future potential for 50 TWh annually or maybe even more (see figures 1 and 3 below).

This 50 TWh per annum is divided into 30 TWh for hydro-power and 20 TWh for geothermal: – The mixture is however somewhat uncertain, particularly since a number of hydro-power installations may be deemed environmentally undesirable. On the other hand, it is likely that the figure of 20 TWh annually for geothermally produced electricity is an underestimate, explains Thorkell Helgason, director at Iceland's National Energy Authority.

– So far ideas exist in respect of further expansion to 28-30 TWh annually by 2015. This expansion, if realized, would occur via a combination of hydro-stations and several geothermal installations, says Helgason.

But if Iceland decides to expand to 50 TWh a year that would indicate a production of electricity more than three times the 2008 level. In official plans no dates given as to when such goals should be achieved. In the table below the Journal of Nordregio has assumed 2025. One should note how ever that the after the currently ongoing expansion power production will nevertheless only amount to perhaps one-third of our assumed 2025-figure.

Included in these predictions is the building of the two new aluminium plants, at present under discussion. One is to be located in Husavik, on the north coast. The site for the other is in Helguvik, a few kilometres west of the international airport at Keflavik. The possible expansion that Alcan wants to undertake at the exiting aluminium smelter in Straumsvik/ Hafnarfjördur could also be included here. Altogether we should thus calculate for the consumption of three new plants to be 10 TWh per year, giving a total domestic consumption of 25 TWh annually.

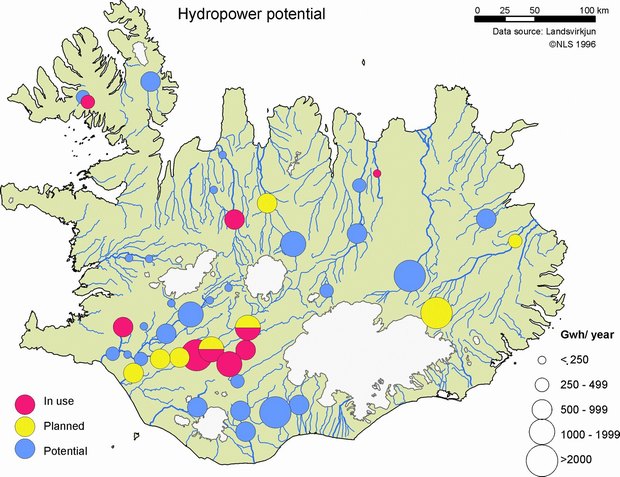

On Orkustofnun's list of possible new plants to supply this new aluminium production, 14 of the new/up-graded hydro-power units and 19 geothermal units currently exist. Of the 33 in total, 21 are in South Iceland and 12 in the northern part of the country. – But there

are currently no plans for any more large hydro-power plants like that now being finalised at Kárahnjúkar, Helgason underlines.

The electricity not consumed by the heavy industry sector in Iceland has for many years reached around 3 TWh annually. – This will only increase in line with population growth, i.e. slowly, underlines Helgason. – as Iceland already has one of the highest household energy consumption rates in the world.

In other words, if the new industrial plants, or similar facilities, are readied for production by 2015 and the production of electricity has been expanded to provide some 25 TWh a year, this would leave Iceland with another 25 TWh of power potential for other uses such as

direct export every year.

In comparison, it can be noted that a large Swedish-based nuclear power-station like Forsmark (I+II+III) has an annual production 24-25 TWh. Similarly the new ocean-cable very recently installed between Norway and the Netherlands can, if the electricity only flows in one direction, transport up to some 6 TWh per year. So in order to send 25 TWh of electricity from Iceland to the European market every year four such cables would be needed.

However Dr. Helgason, does not subscribe to this vision and says that the a political debate on the pros and cons of direct export of electricity has not yet taken place in Iceland.

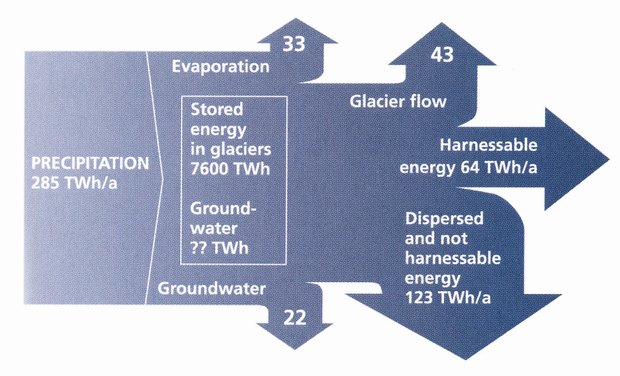

Fig 1. Hydropower derived from precipitation in Iceland.

Map of hydro-power potentials is produced by Nordregio based on similar produced by Landsvirkjun, Iceland's state-owned national power company. Source: Energy in Iceland, published by the National Energy Authority / Ministry of Industry and Commerce, Reykjavik, September 2006.

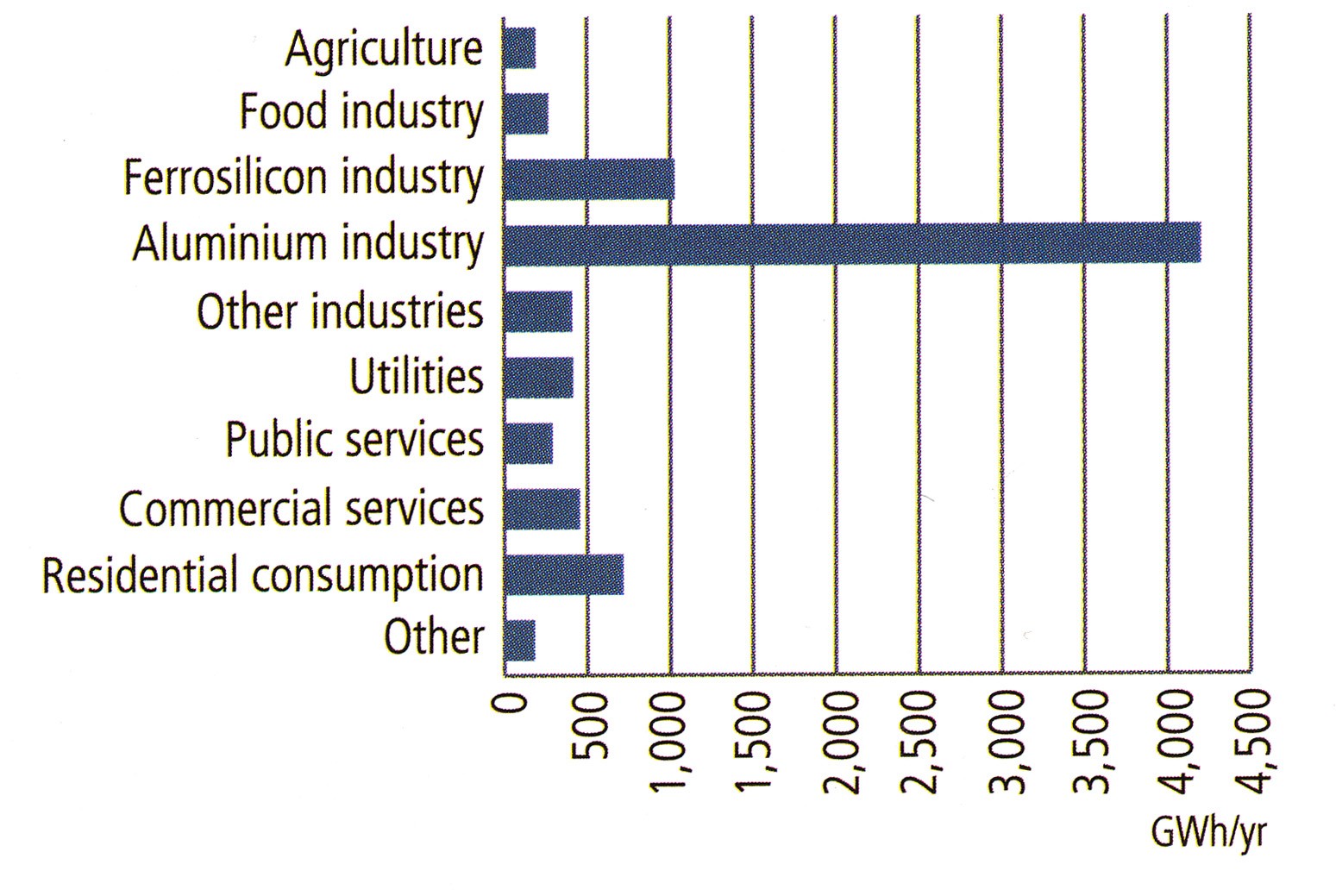

Fig 2. Electricity consumption in 2005.

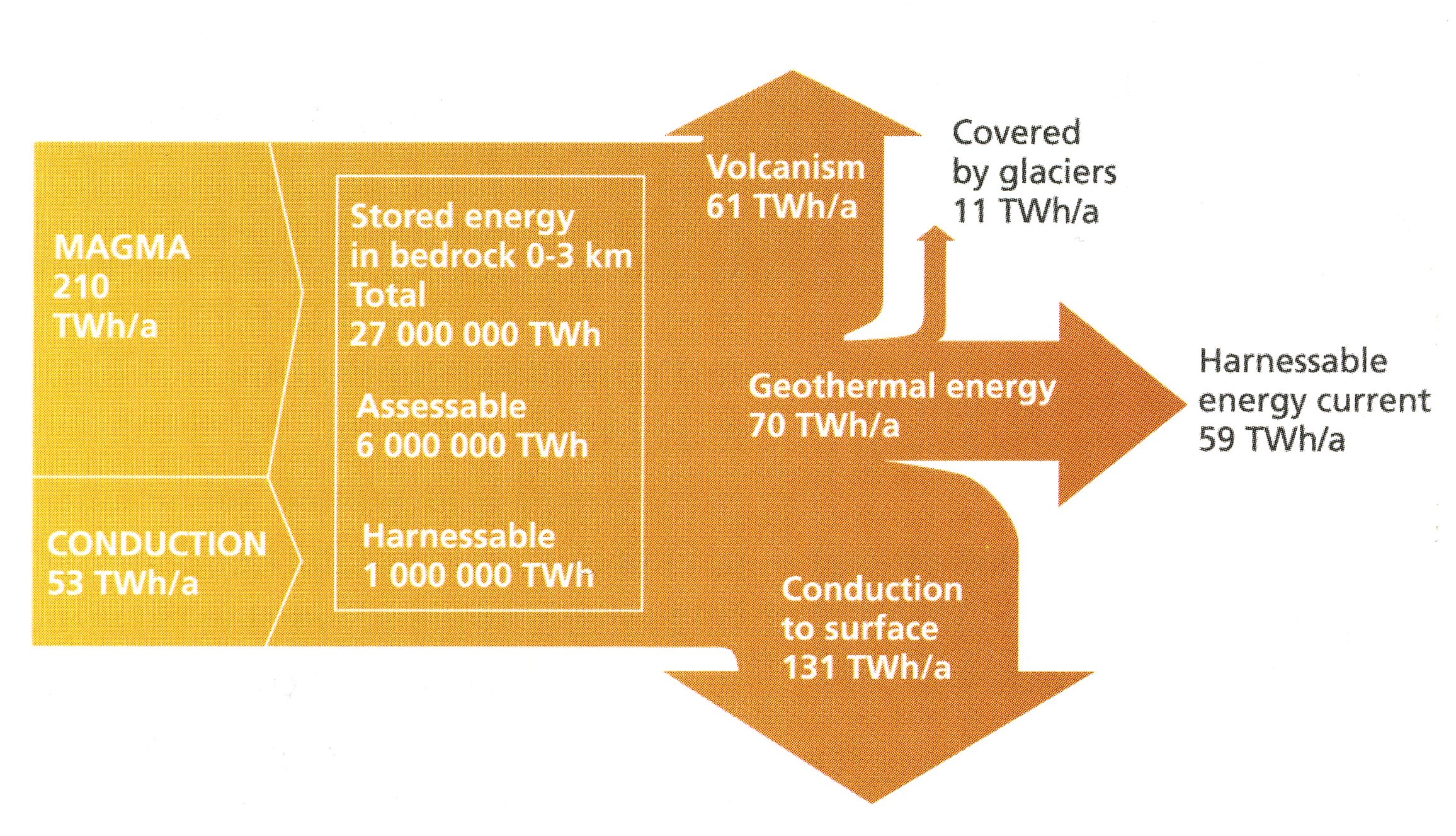

Fig 3. Terrestrial energy current through the crust of Iceland. Click to view larger image.

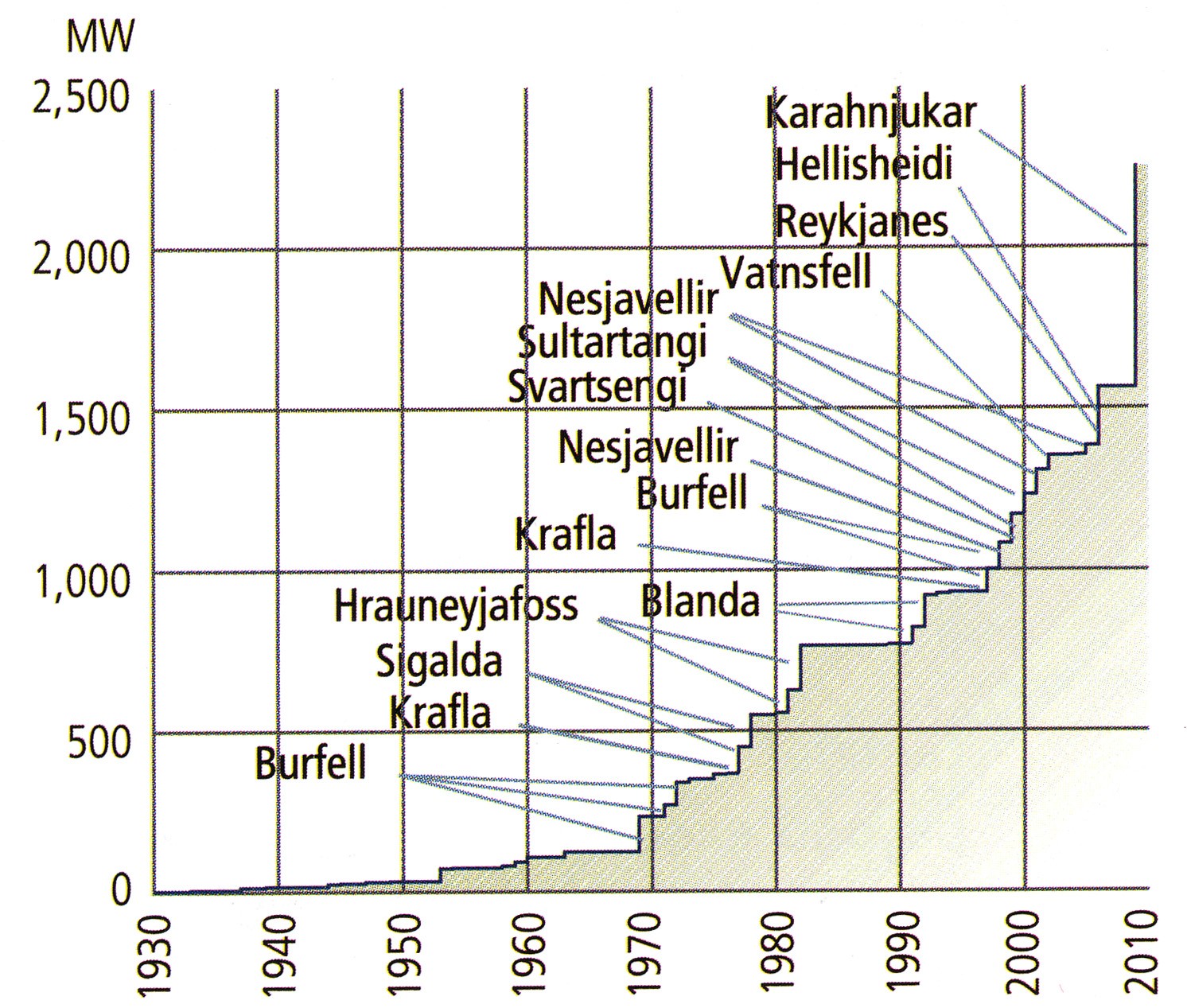

Fig 4. Total installed capacity of hydro and geothermal power plants in Iceland.

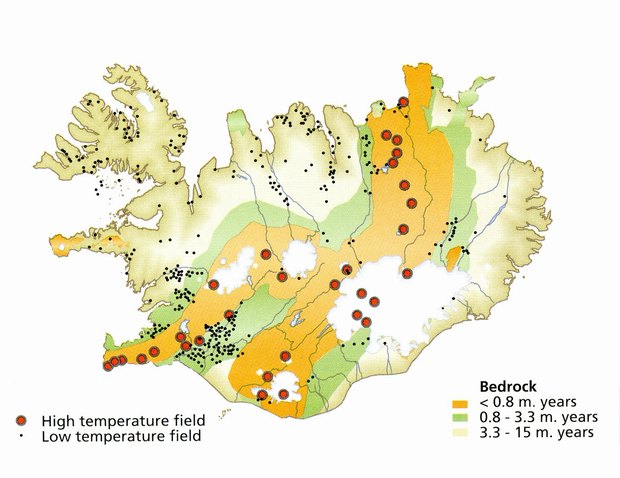

Geothermal fields

Map of Iceland's geothermal fields.

Source: Energy in Iceland, published by the National Energy Authority /

Ministry of Industry and Commerce,Reykjavik, September 2006.

By Odd Iglebaek