Europe is here to stay? Photo: Scanpix

The European Treaty was finally signed in 2007 and will certainly not be re-negotiated within the next decade. The Schengen Agreement has opened borders within Europe. As such, nearly all of the big decisions, which could potentially have an impact on the European space, have already been taken.

This is certainly true for Western Europe, where extensive legal and participatory planning processes often cause lengthy decision-making delays in major construction projects. Consequently, new infrastructure systems cannot be put in place within a decade. Large Trans-European transport corridors have however been agreed and now exist in a more or less fixed form on paper (see maps pp 16-17).

The network of European high-speed railways has been determined. This is similarly true for the Trans-European motorway system, and the system of international airports and container seaports.

In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe things may be slightly different. There, after the end of the cold war and accession to the European Union, the existing interregional transport infra-structure has still to be matched-up with modern levels of demand. New con-struction in these countries can usually be implemented at a faster pace. Though even there, larger investments require time for planning, financing and implementation.

Other factors influencing spatial development, such as the availability and cost of energy, water shortages or the financing conditions for private housing development, are however rather more difficult to forecast.

Finally, governance structures in Europe will not change much either. The multi-level four to six tier system of mixed top-down & bottom-up governance will continue to set the politico-administrative framework of planning and decision-making.

Consequently spatial changes in Europe up to 2020 will only occur on a micro scale. They may occur within metro-politan agglomerations, in peripheral regions, or at locations where decisions on new infrastructure will improve acces-sibility and connectivity. That is why much of the European space in 2020, only three years after the new European "Constitution" will have been ratified, will continue to look much like it does today

In this context, however, one further aspect has to be mentioned. Spatial planning is not a key actor in territorial development in European terms.

Spatial planners tend to overlook the fact that the current mainstream discourse on spatial planning in Europe is very much an academic exercise in "planning poetry", an exercise in using nicely worded phrases to express the objective and subjective concerns of spatial planning.

Well worded documents on the aims and processes of spatial development, decorated by persuasive narratives, success stories and 'best practice' examples, are written by highly qualified experts in international politico-administrative committees. In the end they have little influence on the corporate worlds of finance and global corporations.

Such documents try to be neutral, non-ideological and well balanced. That is why they rarely touch on the real challenges and why they tend to forget to articulate or to express the contra-dictions of mainstream policies and statements.

Few read references

As a rule, neither multinational corpora-tions, political 'think tanks' and the wider arenas of finance and economics, nor indeed the media world read and even use them as reference documents in their day-to-day decisions. They are exclusively read by a small number of academic experts or by communities of spatial planning practice.

Reference to these documents is made when institutions aim to attract financial means for regional development projects, or for funds to help develop regional development strategies. This is then why planners have to be aware that spatial planning has no real influence on the use of macro- or even meso-space in Europe.

The implementation instruments of spatial planning have always been weak. Legal frameworks may control development, where it is envisaged, promoted and politically approved. Financial instruments, with the exception of the European regional funds, are, as a rule however, not available.

Only the inner circles

What remains, is the discourse power of spatial planning, though most discourses remain confined to the inner circles of the national and international communities of spatial planners. The Territorial Agenda and the Leipzig Charter do however remain well-intentioned and ambitious pamphlets for sustainable and socially responsible spatial development in Europe.

They will nevertheless, have only a very limited impact on day-to-day spatial development policies. For many public and private investors they are merely reference documents to justify their own decisions and to pave the way for projects which have already received political clearance.

Energy geopolitics may, in the end, be more influential on territorial develop-ment than national state policies or the European Union when it comes to influencing mobility patterns and residential behaviour. The global exchange markets or the powerful global oil producers and traders, such as Shell, Exxon or BP have a greater influence on spatial development than spatial planners even where planners are backed by strong state governments, as in China.

Trends in European Development

The ongoing trends of European spatial development are widely known and have often been described. ESPON in particular has played a crucial role in providing comparative evidence on the manifold spatial implications of globalization and technological change for the cities and regions of Europe. Spatial development in Europe is characterized by three mega-trends, namely metropolisation, fragmentation and polarization.

Metropolisation:

In essence, all quantitative and qualitative research has confirmed that future spatial development in Europe will predominantly take place in the larger and smaller metropolitan regions. Spatial development processes within these metropolitan regions may however differ from country to country, depending on cultural, social, environmental economic and democratic traditions and values, and on a willingness to accept state guidance and intervention.

In times of globalization economic rationales will clearly dominate the use of metropolitan space. The capital cities of the 27 states of the European Union and the capital city regions of larger regions or states, such as those in Germany, France or Italy, are the hubs of the European infrastructure networks and the preferred locations for qualified and mobile labour.

Knowing that it is almost impossible to reverse this trend, public policy makers promote metropolisation strategies in order to strengthen the international competitiveness of national metropolitan regions. That is why flagship projects and political and cultural events, as well as property markets, tend to flourish in such locations.

Specialisation and fragmentation:

Globalization and economies of scale cause spatial specialization and spatial fragmentation at all spatial levels, at the European, as well as at the national or metropolitan levels. The economies of scale and division of labour paradigms favour the clustering of specialised production and services at selected locations while also defining and determining the respective location factors.

This results in a kind of spatial archipelago of mono-functional, globally interwoven islands. These urban or semi-urban islands are the life- and work-spaces of people, who traditionally reside and work in such regions, or have chosen to live there temporarily. Such "islands" are attractive financial centres in city cores, or backwater areas in the metropolitan fringe, post-industrial districts in new technopoles, or hedonistic second home regions in the gentrified metropolitan periphery.

Polarisation:

The ambitious market-driven European project gradually reduces disparities within Europe. The economic gap between the richer and the poorer states is slowly narrowing. The former Eastern European countries are gradually moving closer to the economic level of the affluent member states in Western and Northern Europe. The market-driven economy in the European Union is then an effective mechanism fostering sustainable economic growth.

However, while national disparities between countries are slowly diminishing, disparities within countries, regions and cities are increasing. In this respect the Lisbon agenda and EU cohesion 'jargon' clearly contradict each other, while the Gothenburg Agenda's ideas have, in reality, not received much political support.

The market-driven neo-liberal policies currently favoured tend rather to increase spatial disparities at the cost of less "talented" or neglected loser regions. The promised trickle-down effects, in the end may not work, and polarization at all spatial levels in Europe becomes the unintended but politically accepted consequence.

These mega-trends, in quite different modes, affect territorial development in three spatial categories, in, or rather within the metropolitan regions: in the metropolitan periphery, and in the European periphery in Northern, Southern or Eastern Europe.

Peripheries as losers?

Metropolitan concentration, spatial specialisation and fragmentation, and spatial polarisation are some of the consequences of globalisation and technological change.

The fierce competition already existing among city regions in Europe for investment, talent and creativity, nurtured by policy advisors, business consultants, researchers and ambitious city leaders, has produced a kind of metropolitan fever. This fever has resulted in the development of ambitious development projects, adorned architecture and impressive bridges, as well as the establishment of mega-events to attract tourists and the media.

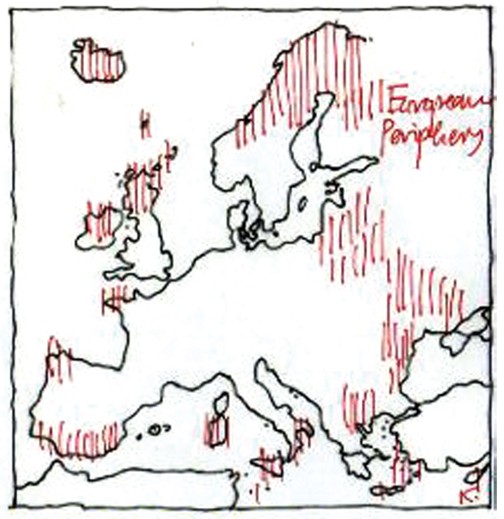

Such metropolitan fever tends to leave some territories in Europe behind, territories which are geographically disadvantaged or do not have a considerable store of endogenous territorial capital at their disposal nor access to the political power, the freedom or the talent to make use of it. At the beginning of the 21st century, three categories of such peripheries can be distinguished, namely (1) the European periphery; (2) the metropolitan periphery; and (3) the inner metropolitan periphery (see figure 1-3).

The European periphery

The European periphery

comprises the territories in the Northern, Eastern and Southern fringes of Europe. Geographical periphery, however, is a question of perspective. The geographical location and the cultural background of the observer, alter the perception of spatial peripheries in Europe. Sardinia, seen from Spitsbergen, is clearly a peripheral region, though this may not be so when seen from Greece. Similarly, Northern Sweden or Finland, seen from Malta, are peripheral regions, though this undoubtedly changes if these regions are viewed from Norway.

However, what remains is that peripheral territories in Europe are less accessible and have lower population densities with all the related social implications for the people still living and working in them. And often they are additionally disadvantaged by extreme climatic conditions and the existence of sensitive eco-systems.

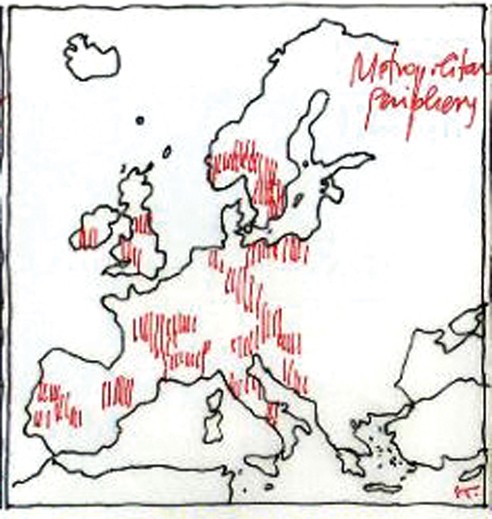

The metropolitan periphery

The metropolitan periphery

is made up of those territories, which, as a rule, are more than 100 kilometres away from the closest metropolitan core. In periods of globalization, metropolitan peripheries are disadvantaged by means of their limited accessibility to the metropolitan core and by size of their labour market, as well as in their access to all of the cultural and social facilities, that only a metropolis can provide.

Unless medium-sized cities with significant territorial capital and a strong export-oriented regional economy provide such services, the more active and younger segment of the regional population tends to leave such regions behind, heading for the more attractive metropolitan cores. By more effectively linking these regions to the metropolitan core, the core and a few locations along the European transport corridors will benefit.

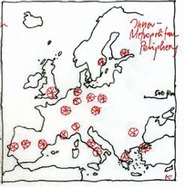

The inner-metropolitan periphery

includes peripheries found in all European metropolitan regions, most prominently in the banlieue of Paris, though also in and around Greater London, in Rome, Madrid and in Berlin.

includes peripheries found in all European metropolitan regions, most prominently in the banlieue of Paris, though also in and around Greater London, in Rome, Madrid and in Berlin.

This inner-metropolitan periphery is characterized by a high degree of unemployment and above average crime rates, by a low quality of educational and social infrastructure, low levels of personal security and a significantly lower environmental and aesthetic neighbour-hood quality.

The inner-metropolitan periphery is the "no go" area for the winners of globalization, and the refuge of the losers. It is in the inner-metropolitan periphery that formal and illegal migrants from ethnic minorities find their relative freedom, as it is in these places that they can afford to live, and are able to set up their (second) home territories.

Obviously, spatial or territorial planning cannot solve all of the spatial development problems in the European peripheries. Each requires rather different and integrated policy actions at all tiers of planning and decision-making. The information power of space-focussed planning and communication compe-tence can however trigger targeted discourses on how to cope with such challenges.

Possible European Futures:

Many ways exist to describe the possible futures of the European space within the framework of mega-trends, as is briefly sketched out above. While spatial development on the European macro-space will not alter the geographical distribution of economically successful regions in Europe, infrastructural and property development decisions in the decade to come may have some impact on the meso-level, depending on geopolitical developments, energy-related changes in mobility, governance structures, and consumer values. The following five scenarios will sketch five alternative corridors of spatial development in Europe.

Business as usual:

Business as usual:

Future spatial development in Europe will continue to reflect the dynamics of economic development, the power of market forces and non-interventionist neo-liberal policies. In consequence, metropolitan regions in Western Europe will continue to grow, despite the rhetorical efforts towards decentralization at the political level. London will further expand into South East England from Coventry to Brighton. This is similarly true for Paris, or rather the agglomeration of Ile-de France, where, despite all national efforts to balance spatial development in the country by promoting other metropolitan regions and "pays", a recent effort to enhance endogenous development across the nation.

Hyper-urbanization in most European metropolitan regions will further increase commuting times. And when car-commuting times exceed acceptable and affordable thresholds, new public transport lines will accommodate the expansion and foster even further extension. All other European countries will similarly experience the growth of their capital regions at the cost of the more peripheral territories.

The speed of urban expansion will generally depend on demographic trends and value-driven housing policies. This is as valid for Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece, as it is for the Nordic Countries, the Baltic States and for all the countries in Central, Eastern and South-eastern Europe. Despite ambitious political agendas of spatial decentralization and territorial cohesion, there is little hope that a more balanced spatial development can really be achieved.

Migration flows from Africa will not come to a standstill. Areas, where informal labour is sought or where cultural linkages exist, will be the preferred location-targets of these migrants, adding new social challenges to the in-trays of the respective local and regional governments. Intra-regional disparities within metropolitan regions will thus continue to grow.

In order to remain globally competitive, the Lisbon Agenda will justify and demand more support than the environmentally-focused Gothenburg Agenda. European and national subsidies will support competitive regional economies, which, as a rule, are located in the metropolitan regions.

To speed territorial cohesion and to strengthen the competitiveness of these regions, Trans-European transport corridors and the extension of international airports will receive high political priority. High-speed trains will inter-connect the metropolitan regions in Europe and thus further support the ongoing metropolitan concentration processes.

Energy policies will certainly aim to increase the share of renewable energy resources. In this context, biomass production will increase, and this, in turn, will have substantial implications for agricultural and rural development policies, and on the natural and cultural landscapes of the diverse regions of Europe.

The Mediterranean Pact:

The Mediterranean Pact:

In the South, the European Union borders North Africa and the Middle East. To better integrate North Africa, the Middle East and Southern Europe, (and possibly Turkey). a Mediterranean Pact has long been proposed by the French Government.

The idea of the French fathers of this idea, is that such a pact, - not surprisingly, should be under the regional leadership of France - , and together with Italy, Spain, Portugal, Cyprus and Malta, all of the countries facing the Mediterranean coast from Mauritania to Israel, and including Egypt, the Palestinian Authority, Lebanon and Israel, would form a powerful economic community in the transition zone between Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

The circles, promoting this pact believe that such a geopolitical initiative could indeed address a number of unsolved European issues, and deal with some of the economic and political challenges, faced along the Mediterranean Sea (e.g. structural unemployment, illegal migration, attempts by single countries to apply for EU- Membership).

Such a pact could, at least in the long run, establish a large and strong economic belt across Northern Africa, with global economic production zones, using labour from Africa, which otherwise, as experience shows, attempts to reach cities and regions in the established European Community.

For cultural reasons African labour would prefer to stay in the region, once economic prospects look more favourable at home. Migration to Western Europe would diminish. One could even expect that qualified labour from ethnic communities in Western and Central Europe may consider relocating to the new global production zones in Northern Africa, where, as some observers suggest that Christian and Islamic values could better co-exist, although the experience in the Sudan is not very encouraging in this respect.

Whether the still controversial issue of Turkey becoming a member of the European Union could be elegantly evaded in such a pact, remains doubtful, even if the country will then be entrusted with a leading role in such a venture.

With the establishment of such a Pact, Trans-European Transport corridors in the South would receive higher priority and new Mediterranean Sea corridors would become a new option for sustainable long haul transport. The sustainability dimensions of spatial development would certainly receive only lukewarm political support, given the traditional socio-political milieus of clientilism.

In such a scenario, the economic gravity of Europe would certainly shift to the South. Following the rationale of spatial development in market-led economic development, Metropolitan regions in Southern France, Spain, Portugal and Italy would find particular advantage in the Pact. Linked to the metropolitan regions, even port cities and networks of small and medium-sized cities in the region could strengthen their positions and gain from this geopolitical initiative.

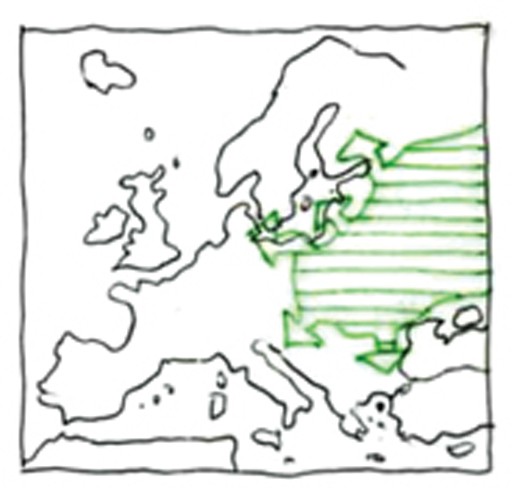

The Eastern European Pact:

The Eastern European Pact:

Similar to the example of the Medi-terranean Pact, the countries of Central Europe may consider initiating another geopolitical pact with the countries of Eastern and South-eastern Europe, such as The Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova and with Serbia, Macedonia, Albania and Montenegro. This pact could even include the European territory of Russia. Even though current agreements with the EU may discourage these countries, from considering such a geopolitical initiative.

The EU already distinguishes between these two groups of countries, the former are recipients of the EU's 'Neigh-bourhood Policy' the latter already have what is called 'an entry perspective' to the EU – they are treated distinctly and the Balkan countries would not want to lose this 'preferential treatment' basis with a strong economic focus which would open the door to the establishment of further industrial zones in Eastern Europe, which may accommodate industrial production from Western Europe, searching for locations with cheaper labour costs and better accessibility to new consumers. In this scenario, industrial mass production would shift gradually to Eastern Europe.

For European corporations and businesses the countries of such an Eastern European Community would certainly be a serious alternative to China and Southeast Asia. Driven by such a pact, Eastern European countries would catch-up faster with Western Europe. Among the many implications of such a shift to Eastern Europe, East-West migration flows to Western Europe, particularly to Britain, would decline.

The Eastern European pact would certainly accelerate the extension of the Trans-European transport corridors, to and across, Eastern Europe and Russia. In such a scenario Berlin, too, could resume its traditional role as the cultural centre of East-West exchange.

The winners of accelerated economic growth in Eastern Europe would be Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary. Consequently, the metropolitan regions in these countries, already benefiting from accession to the European Union, would experience even faster economic growth. From the resulting economic effects, smaller and medium-sized urban settlements in the East could perhaps envisage a brighter future.

Given the immense availability of space, the Eastern European Pact could also boost modern agricultural production in Eastern Europe, and strengthen the role of the region as the 'granary of Europe'.

China's European March

China's European March

By the turn of the 21st century China had become an economic world power. Favoured by globalisation processes, information and communications changes, and the logistics revolution, China's economic growth has increasingly come to impact on economic development elsewhere in the world, particularly in "old" Europe.

The economic repercussions can already be felt in many locations. Increasingly, Chinese production complexes are thriving in Italy and France, in Spain and in Romania, eventually this will be so in Northern Africa, too. European port cities (Hamburg, Rotterdam, Antwerp and Naples) are handling more and more containers arriving from China, and more and more containers with sophisticated European products are supplying Chinese industries and consumers with advanced technology and luxury consumer goods.

European financial centres (London, Frankfurt, and Paris etc) are aware of the growing importance of China's role in the global financial system. European engineers, architects and planners are much involved in ambitious Chinese projects. French luxury brands sell well in the Chinese market, and French architects are among the winners of this internal European competition for contracts from influential city mayors, who wish to gain eternal fame from fancy urban monuments.

Mayors forge twin-city arrangements with Chinese cities to prepare the ground for business co-operation. And local economic development agencies make much effort to attract Chinese investment to the continent, to participate in the economic success story of the Asian giant. Chinese modern art is experiencing impressive success on the global market and is flourishing in galleries around the world.

Chinese students have discovered Europe as a place to learn, and Chinese tourists, touring around Europe in five, seven or even ten days, have already replaced Japanese travellers as the leading Asian tourist nation. In Europe sentiments waver between cheering the new market opportunities and painting the Chinese peril on the wall, as has occurred more than once during the last century. Unless local conflicts heat up local politics, as in Milan, Naples or in Paris, local governments tend however to view the Chinese challenge with great serenity.

Though Chinese challenges in respect of city development in Europe may still be negligible it would make sense to be aware of the likely urban implications of China's rise. At present it is mainly low cost Chinese production, in China and increasingly in Chinese enclaves in Europe, which is alarming labour organisations.

Will all these European industries, which are flourishing due to the insatiable Chinese market, continue to do so, or rather will high quality Chinese products challenge them? Will the European automobile industry continue to benefit from exploding mobility across China, or rather, will China export cheaper eco-cars to Europe? Will technological advancement and design quality remain the most essential assets of European industry? Will Chinese investments in European financial institutions make the European banking system more vulnerable? Will the insatiable Chinese hunger for gasoline constrain the energy supply for European consumers and reduce their mobility? Will Chinese higher education, research and development make the country fully competitive with Europe within less than a generation?

These and other developments in China linked to such questions may have implications for the cities of Europe, whether they host the automobile industry, or whether they still benefit from local fashion, design or environmental technology clusters. The consequences for employment and the quality of life, and, in the end, for the traditional European model of 'tamed', socially responsible capitalism will also be experienced.

Slowpark Europe

Slowpark Europe

The global division of labour and technological changes have led to increasing competition among cities and regions in Europe. Local or regional economies relying heavily on the export of products and services abroad will not remain on the competitive edge unless they export parts of their production chains to Asia, or to Eastern Europe, where labour costs are cheaper. Increasing productivity and investing in high-end technologies at home, or shifting even more production to low-cost areas are the only alternatives here.

Both options would have considerable implications for regional employment. Under such circumstances, it may be worthwhile exploring how the dependence of local and regional economies on global markets could be gradually reduced, and how the paradigms of the division of labour and economies of scale could be reviewed.

Following the principles of sustainability, as expressed in the Gothenburg Charter, strategic regional development could favour regional economies and regional economic circuits. Based on the rationale of endogenous regional development urban-rural economies could be re-integrated to sustain regional employment. The trend towards healthy food may help to promote such strategies.

Less car mobility

The principles and criteria of the holistic 'slow city movement', originating from Italy's 'slow food' development, could be a good starting point here to reformulate local development strategies. The key to such development could be the gradual reduction of unnecessary individual car mobility, the promotion of more intelligent logistic flows and the reduced flow of goods within metropolitan regions. These may in any case be an inevitable consequence of increasing energy costs.

Non-growth

Such deliberations are particularly valid for the regions beyond the large urban agglomerations, the metropolitan and the European peripheries, as defined above. Policies designed to produce alternatives to the model of economic growth and competition may in the end lead to a non-growth continent, where, with the exception of a few large metropolitan areas, the regions of European history and tradition, their attractive landscapes, their cultural diversity and quality of life, their cultural life and creativity, may become a kind of a healthy "Slowpark Europe".

Prodution to Asia

While Asia, with its unlimited human resources, is taking over most of the globe's industrial production, particularly mass production, much of Europe's territory is becoming a kind of a large theme park for history and culture, filled with appealing small and medium-sized cities, 'gown towns' providing excellent post-graduate and post-doctoral education in inspiring environments, with attractive landscapes where food and wine is being produced and consumed.

Europe here would become a continent of cultural and creative industries and related educational institutions, a preferred target for cultural tourism and learning holidays. Servicing these target groups will become the main sector of employment.

Accept lower income

Most inhabitants of Slowpark Europe, particularly the lower and middle classes, may have to accept slightly lower income levels and lower pensions. The consequence of this however will be a reduction in consumer power, which in turn will reduce holiday expenditure and see less investment being made in property, cars and luxury goods. In Slowpark Europe, forests and nature parks will expand into areas where population decline has contributed much to the erosion of regional economies and public infrastructure.

These five scenarios reflect a subjective view of possible development trends in Europe. None will become the reality, though single elements may have to be faced at the various tiers of planning and decision-making.

Spatial Planning and Research

What then are the conclusions to be drawn from these spatial planning and research scenarios for Europe? Despite a plethora of academic publications on urban and regional development our knowledge of the various factors influencing spatial development in Europe remains limited.

Consequently, in order to be better equipped for the spatial challenges ahead, still more research will have to be done, not so much on the pet-themes of parti-cipation, governance or cluster develop-ment, but rather more on the complex energy issue of mobility and logistic flows, on the implications of geopolitical developments on space, or the influential role of value systems on locational choice and on bridging sector policies with spatial policies. Areas worthy of further rigorous exploration include:

The energy-environment-mobility com-plex and its implications for macro-, meso- and micro space, including the role that changing consumer values play in this context.

The spatial implications of geopolitical developments in Eastern Europe, Asia, the Middle East and the Mediterranean for the cities and regions of Europe.

The spatial consequences and potentials of new ITC technologies, particularly for the delivery of public and private services to people and small and medium-size enterprises in the metropolitan and European peripheries.

The implications of global property investment strategies on urban develop-ment.

The methodology and implementation of integrated strategies for coherent polycentric inner-metropolitan develop-ment. Here, more 'governance' and less 'evidence-based' research seems to be necessary, while more insight is needed into how to deal with the cultural and economic role of the various groups of migrants and ethnic communities that now live and work in most European cities.

Planners should remain humble and patient, as well as ambitious and committed. On the one hand they should acknowledge that their power to guide spatial development and to defend green-field consumption against infrastructural development and property speculation is quite limited. While on the other, they should not surrender to neo-liberal attitudes and short-term incrementalism.

It is still the task of planners to develop longer-term visions and to seek spatial justice. Without allies in the "real" world however their visions and concerns will not be heard. Thus they must seek, wherever possible, to construct strategic alliances with those who have more influence in society.

By Klaus R. Kunzmann, Professor

Interview with Klaus R. Kunzmann